Quarterly Publication - January 2017

Politics and economics collide...again - January 2017

2016 was a year marked by unexpected political and economic outcomes, which set the scene for great uncertainty in 2017. The UK referendum result opting to leave the EU and president Trump’s electoral victory in the US both highlighted dissatisfaction in developed economies with the outcomes of the economic policies established since the 1980s. At the heart of the discontent is the belief – rightly or wrongly – that the liberal policies that emerged from the Washington Consensus (broadly, a policy set that advocates free trade and free markets) are responsible for lost income, unemployment, diminished gains in living standards and entrenched levels of inequality. These sentiments are likely to play a dominant role in shaping political outcomes in the year ahead, which features a heavy election calendar that includes a number of key European countries. This may see political events emerging as more significant market drivers than cyclical or structural factors – and more so than in many years before.

POLITICS AT THE FOREFRONT

We need to start with the elephant in the room: Trump as US president. The US election outcome was a major surprise and there is significant uncertainty about the makeup of Trump’s administration and the future course of US policy – including whether or not there will be changes to trade and fiscal policies, as well as key policymaking leadership. We simply do not know what the impact on economics and markets will be. This uncertainty is more pronounced than that created by Brexit, which is, ultimately, a decision on a single proposal that will dictate a future course of action. The outcomes stemming from the US election are more complex and open-ended.

Trump has made such a range of controversial – and at times contradictory – statements about his intended policies on almost all important issues that we are forced to wait and see what comes. What we do know is that there are a number of key priorities for the new administration, including tax and fiscal stimulus for the US economy, and trade and immigration policies for the global economy. On the former, markets have been generally optimistic that the proposed combination of preliminary tax cuts, followed by increased state-funded capital expenditure, will boost US growth. The outcomes of changes to global trade and immigration policies to the US remain to be seen, but here Trump has been more forthright and there seems to be a greater degree of reciprocal risk. Certainly, his preference for unpredictability implies increased volatility for markets in 2017. (For a detailed assessment of key developments to look out for during Trump’s presidency, please see the article by our guest contributor, Financial Times chief foreign affairs commentator Gideon Rachman.)

In 2017, there are scheduled elections in the Netherlands, France and Germany, with early elections possible in both the UK (following Brexit) and Italy (following a vote against constitutional reform and the resignation of the former Italian prime minister in December 2016). In all cases, the risk of a non-mainstream party being elected is non-negligible.

Common themes that have featured in European political debate include widespread EU scepticism, a visible rise in support for alternative parties, political fragmentation, and a rejection of liberal economics, globalisation and immigration. As in the US and the UK, the source of dissatisfaction is a combination of stagnant real income growth, high levels of unemployment (notably in the EU periphery) and rising levels of inequality, which have been accompanied by an increase in security concerns.

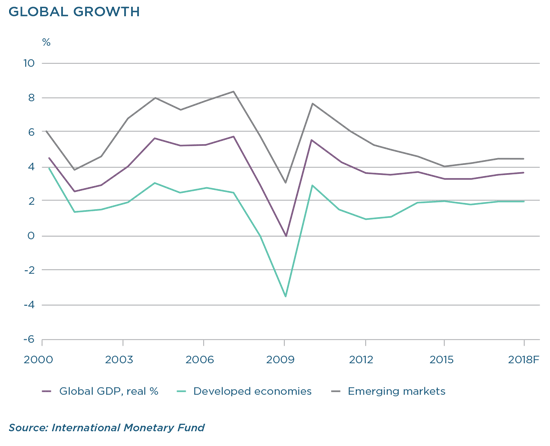

Despite the more visible impact of politics on the markets – and the aftermath of unexpected election outcomes – global economic performance in 2016 was generally better than people had feared, and momentum into early 2017 improved from last year. The baseline projection is for global GDP growth to accelerate from about 3% to about 3.5%, fuelled by some improvement in investment and slightly more fluid global trade. Base effects and higher oil prices, coupled with some underlying improvement in labour market fundamentals, will boost inflation in 2017, providing a decent platform for nominal GDP performance and corporate profitability. Key drivers are stronger US growth and large economies within the emerging complex coming out of recession. Here Russia, Brazil and to a lesser degree Argentina’s prospects look promising, while China seems to have stabilised at around the 6% to 6.5% level. However, this is a relatively benign expectation. It comes with the clear acknowledgement that baselines carry an increased risk of being overtaken by shocks that were assigned low probabilities and were not considered in original forecasts.

INVESTMENT TO RECOVER?

Whether or not global investment spending will recover is a pivotal question for the year ahead. Investment spending was a meaningful contributor to global growth in the years preceding the global financial crisis – a contribution that has more than halved in the period since. Arguably, this partly reflects artificially elevated levels of growth in the prior period, which include various property booms, the boost in Chinese infrastructure spending and massive increases in leverage in the US, UK, Europe, Eastern Europe and China. Since then, however, capital investment spending has remained weak across a broad base, notably in the US and Europe, but elsewhere too.

Most of the current weakness reflects deficient global demand, excess capacity and low levels of investor confidence. Fiscal consolidation has also played a role (but may, at the margin, now be turning). In the US, growth in capital expenditure has been considerably weaker than growth in consumer spending, across a broad base of categories. For example, spending on equipment such as aircraft, railroads, trucks, mining and exploration machinery has slowed meaningfully, dragged down by the mothballing of oil sector-related spending plans in 2015 and 2016.

Some recent recovery in oil prices – coupled with the anticipation that Trump may indeed be able to boost domestic production – could see a revival in US capital expenditure. In addition, prospects for further improvements in investment spending lie in the recovery of emerging markets, which should add positively to global growth momentum. In Russia, higher oil prices and the country’s emergence from its 2015/2016 recession should see capital expenditure pick up. In Brazil, fiscal consolidation, an anticipated upturn following almost two years of economic contraction and a sharp improvement in business confidence should help to ease crowding out by the state and will allow for increased private sector investment. Improvements in demand and commodity prices could also see a small positive boost to investment spending in South Africa. In contrast, capital expenditure in China is unlikely to be a positive contributor to overall growth, given the high base set in 2016. However, equally, we do not expect policymakers to withdraw policies currently supporting growth.

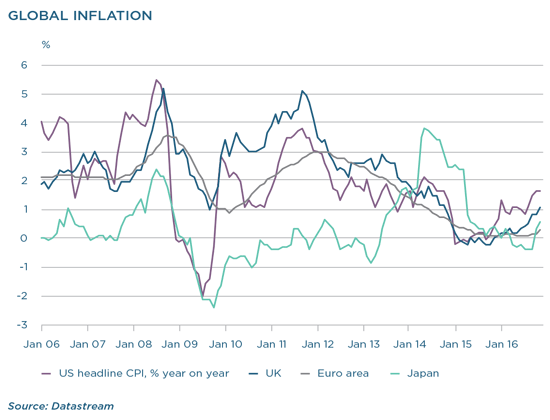

RISING INFLATION

The global recovery following the global financial crisis has been one of the weakest in history. Outside of economies where currency weakness or commodity (food) prices have boosted headline inflation, overall global inflation has remained at historically low levels, despite extremely accommodative policies. However, given the revival in global energy prices, coupled with base effects (and in the case of the US, emerging wage pressures), more broadbased inflationary pressure is likely to emerge. While most economies and central banks are likely to welcome a little inflation, there remains the risk that it runs ahead of what is desirable. For now, the risk of runaway inflation seems low, as credit growth remains subdued.

This is a challenging environment for global central banks, as inflation reaches or exceeds target levels but output gaps remain wide. Low inflation has been an acceptable justification for monetary stimulus, but both the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB) seem to be at the limit of what monetary policy can deliver. The Fed has already started to normalise rate settings, and the minutes from the December Federal Open Market Committee meeting suggest a more hawkish post-election Fed into 2017. While the ECB has extended its asset purchase programme to September 2017, there may well be an announcement by mid-year of its intention to taper its purchases and wind them down over time. There seems little baseline risk of any abrupt changes to policy settings, but markets tend to be very sensitive even to small changes in policy intentions.

CAN FISCAL POLICY BOLSTER GROWTH?

More expansionary US fiscal policy – currently mostly in the form of tax breaks – has boosted expectations of stronger US growth, with global spillovers. With global developed monetary policy settings seemingly at their limits, there have been mounting calls for fiscal policy to provide a platform for stronger growth. Certainly, in many developed economies a combination of fiscal consolidation post the global financial crisis and decaying state infrastructure gives justification for government to play a bigger role in supporting growth.

US fiscal stimulus will probably accelerate, but may take longer than more exuberant current estimates suggest, as priorities of the new administration are unclear (and projects take time to implement).

Outside of the US (and possibly Japan and China), there seems to be little appetite for governments to significantly boost spending. Within Europe, Germany has the most capacity to raise pre-election spending, but increases in refugee-related spending in 2016, coupled with a rise in child benefits and tax cuts, have limited appetite for a major spending spree. France’s pre-election spending prospects are unclear. Italy’s post-referendum agenda is also uncertain and, with its very high level of debt, its government’s ability to spend is severely constrained. Overall, fiscal-related investment spending is unlikely to provide a significant boost to European growth in the coming year.

BETTER PROSPECTS FOR 2017, BUT STRUCTURAL CHALLENGES REMAIN

Global growth momentum looks promising at the outset of 2017. However, structural challenges remain. Global productivity growth has slowed significantly post the global financial crisis, moderating the pace at which households – notably in developed economies – enjoy gains in their standards of living. This, in turn, is likely to continue fuelling political uncertainty and social discontent.

Global trade has also slowed, dragging on growth of major exporting economies, particularly in emerging markets. Part of the explanation may be the slow pace of investment spending, but demographics and high debt levels will remain a long-term constraint. Most importantly, and most uncertainly, political disruption could materially change the path and nature of global economic growth in the year ahead.

United States - Institutional

United States - Institutional