Bond Outlook - July 2017

THE BIGGER PICTURE

In investing, it is dangerous to lose sight of the bigger picture. This is unfortunately easy to do when financial markets consistently deliver short-term disruptions and distractions that obscure the complete view, to the detriment of achieving longer-term objectives. The risk of getting caught up in the detail is best illustrated by an ancient parable. It tells the story of six blind men who came across an elephant for the first time. Each tried to discern what the animal looked like based on the body part they could feel. The blind man who got hold of a leg concluded that an elephant looks like a pillar. Another, who held its tail, surmised that it resembled a rope. The one with its trunk said it was like a tree branch. The man who felt its ear said the elephant was like a hand fan. Feeling the elephant’s belly, another blind man sagely replied that the elephant was like a wall. Lastly, the one who felt its tusk said it was like a solid pipe. Each of them correctly assessed their specific part, but did not realise that the elephant was in fact the sum of all those parts.

Losing sight of the bigger picture is particularly dangerous when change is afoot, as we believe is evident in the SA bond market. The market enjoyed a relatively decent second quarter, with the All Bond Index up 1.5% for the quarter ending 30 June 2017, slightly behind cash (1.9%) but well ahead of inflation-linked bonds (1.0%). In the year to date, bonds remain the star performer in the fixed-income asset class, returning 4.0%, well ahead of cash (3.7%), inflation-linked bonds (0.4%) and even preference shares (2.3%), which have been the stand-out performers over the last 18 to 24 months.

The performance of local bonds was in large part a function of the strong performance of emerging markets, with the JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index (EMBI) Global Diversified composite (a proxy for emerging market bond performance in dollars) returning 2.2% the second quarter and 6.2% year to date. This has supported inflows into the local bond market of approximately R40 billion this year (R21.3 billion in the second quarter), keeping local bond yields relatively well contained despite a deteriorating fundamental backdrop. Key for bond investors is whether current levels in the local bond market are sustainable – or are investors failing to see the bigger picture?

VICIOUS CIRCLE

Over the last quarter, there have been some significant developments on the local front. Firstly, inflation has continued to fall and the SA Reserve Bank (SARB) has started to tilt towards monetary easing as growth collapsed, pushing SA into a technical recession. Much-needed policy reform remains hamstrung by accusations of endemic corruption at the core of government and state-owned companies, pushing policymakers further into a state of paralysis. Confidence in the economy and in the ability of policymakers to make the right decisions has continued to decline, as seen in recent business and consumer confidence indicators. This creates a vicious cycle: no new private or corporate investment is adding to the downside risks and dragging on growth momentum over the next year (and more importantly, over the longer term). The net effect is an economy with no buffer or ability to withstand any further bad news or deterioration in global risk sentiment.

The SA economy is set on a path of deteriorating creditworthiness due to worsening debt and fiscal metrics. Without serious policy action, we will have to endure further downgrades into sub-investment grade over the next 12 months. This will result in our bonds being excluded from key investment indices, which we expect will trigger large outflows from the bond market. The impact will not only be felt in the financial markets, but will inevitably affect the man on the street through higher borrowing costs and possibly higher inflation over the longer term. Accordingly, local economic prospects remain quite dim.

When we were faced with such poor prospects in the past, investors could take comfort in the fact that local asset prices were reflecting the same (if not a greater level) of pessimism. Being able to buy assets at a decent riskadjusted discount helped to compensate for feelings of personal misery. Unfortunately, this is currently not the case, especially in the local bond market, where yields have managed to remain quite stable at relatively expensive levels (8.65% average over the last quarter, reaching a low point of 8.38%). This is primarily due to a renewed global hunt for yield.

KEY RISKS

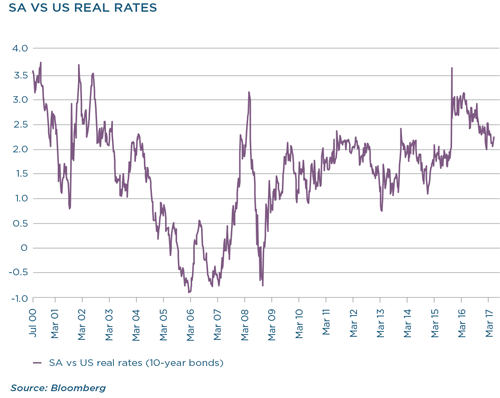

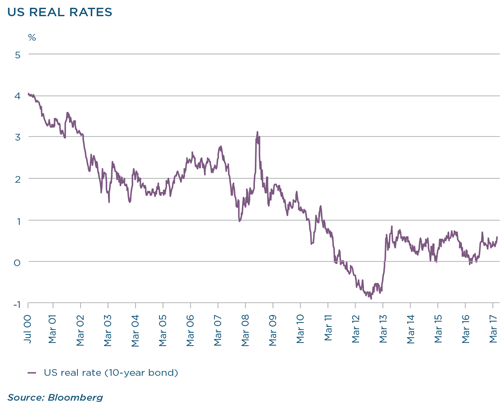

Since the global financial crisis (2008/2009), US 10-year real yields have fallen steadily and traded as low as -1% before settling into a range of 0% to 1% in the last five years. This has anchored global bond yields, supporting the hunt for yield into many emerging and frontier markets. The implied real yield of SA 10-year bonds, which has been oscillating between 1% and 2% above the US 10-year real yields, looked quite attractive. The implied 10-year real yield is calculated by using a static inflation assumption of the realised inflation average (5.8%) over the period. The key risks to SA government bond yields are whether US 10-year real yields (currently at 0.57%) will remain below 1% over the long term, and whether SA bonds are trading at a fair price relative to US bonds. SA’s implied 10-year real rates currently trade at a spread differential of approximately 2% to US 10-year real rates. This is probably insufficient given SA’s deteriorating macroeconomic backdrop. If anything, this spread represents the best possible scenario.

The current key US interest rate sits between 1% to 1.25%, with the Federal Reserve (Fed) expected to hike it to 3% over the longer term. Inflation in the US, as measured by the Fed’s chosen measure (personal consumption expenditure) sits at 1.4%, but is expected to move towards the Fed’s target of 2%. This implies that currently the real US policy rate is at -0.39% (very accommodative, considering that growth is above 2%). Over the longer term, this will move to around 1% (assuming inflation of 2% and the Fed’s interest rate of 3%).

Based on these numbers, it is apparent that there are two key risks to the current level of the US 10-year real rates. Firstly, the US policy rate is too accommodative, and should move towards a more appropriate level. Secondly, if the US policy rate moves towards a real rate of 1%, then US 10-year real yields at 0.57% (or even sub 1%) are not sustainable. Taking a step back to examine the bigger picture, it is clear that SA government bonds are at risk of widening given the combination of strong upside risk to US real yields and a SA risk premium that is priced only for very good domestic news.

OUR VIEW

At Coronation, we aim to construct portfolios that are well diversified, robust and resilient. So, given that we are cautious on almost 70% of its investable universe, where are we investing our bond portfolio? Two key areas in the SA bond market are starting to look quite interesting, the first being shorter-dated inflation-linked bonds (ILBs) and the second, the long end of the government curve.

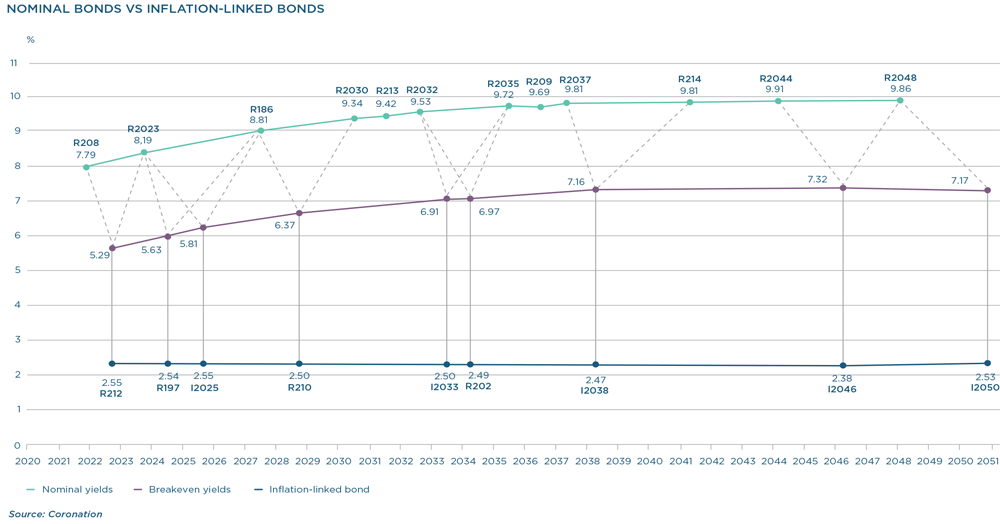

The ILB curve (the lowest line in the graph overleaf) is currently very flat, with almost all bonds trading at 2.5%. SA’s repo rate is at 7%, implying a real policy rate of 1.5% (assumed inflation at 5.4%). This implies one can buy a short-dated ILB (five-year maturity) at a spread of 1% above policy rates, which is quite attractive, especially when one considers that over the next 12 to 18 months, the policy rate in SA will probably moderate by around 50 basis points (bps), which will act as a strong anchor for shorter-dated ILBs. In addition, from a total return perspective, if inflation averages 5% over the next year, the five-year ILB will return 7.8%, which is slightly higher than the equivalent five-year nominal government bond. However, in the case of inflation averaging 5.5% to 6%, the ILB will return 8.33% to 8.82%. In the worst-case scenario, this asset provides one with an equivalent nominal bond return but gives one added protection in the case of an upside surprise in inflation. This makes an ILB an attractive alternative to a nominal SA government bond, especially in a traditional bond portfolio. Due to the flatness of the ILB curve, the implied breakeven levels for longer-dated ILBs (greater than 15 years) sit north of 6.5% (the middle line in the graph above), compared to the shorter-end ILBs (five years) being closer to 5%. Breakeven inflation is where the market expects inflation to average over the life of the underlying bond, so in the case of an ILB with a maturity greater than 15 years, one would need inflation to average above 6.5% before the ILB outperforms its nominal equivalent – a highly unlikely scenario considering we have an inflation-targeting central bank. This further enhances the relative attractiveness of the shorter-dated ILB since breakeven inflation expectations are closer to 5%.

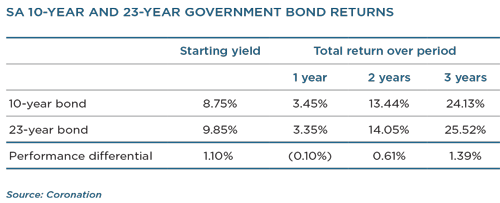

As we have outlined, SA 10-year government bonds are not appealing. So why would we be interested in government bonds on the longer end of the curve (more than 15 years), which traditionally are even riskier? It is important to note that at Coronation, we do not position a portfolio for only a single outcome. Our portfolios are carefully constructed to make sure that as a whole they should create attractive longer-term returns. Our historical analysis suggests that over the last 15 years the longer end of the bond curve has only a maximum of a 50% correlation to the 10-year area of the curve (if the 10-year bond rallies/sells off 100 bps, then the greater-than-20-year bond only rallies/sells off 50 bps). In addition, given that over the next 12 to 18 months, the SARB is likely to reduce the repo rate by 50 bps, these longer-end bond yields of close to 10% are going to find it difficult to move out 100 bps, in line with the 10-year benchmark, as their relative attractiveness to cash rates will be hard to ignore. What this implies is that we are likely to see a flattening of the bond curve in the event of a 100 bps sell-off in the benchmark. However, one might argue that given that the sell-off in bond yields will probably be driven by a weakening in SA’s fiscal and debt metrics, it is highly unlikely that we only see a 50 bps sell-off in 23-year bond yields if 10-year bond yields sell off 100 bps. Therefore we need to be extra conservative. Let us assume the 23-year bond sells off 80 bps, in the event of a 100 bps sell-off in the 10-year benchmark. In the table below, we show the total return numbers over various time periods, based on a 100 bps sell-off in the 10-year bond and an 80 bps sell-off in the 23-year bond.

It is clear that in periods greater than a year, the 23-year bond actually outperforms – demonstrating how powerful yield can be over the longer term. Longer-end bonds definitely carry greater risk, but investors are more than adequately compensated for this risk in the spread relative to the 10- year benchmark. Accordingly, longer-end bonds are an attractive alternative within a bond portfolio.

Given the local macroeconomic backdrop, we remain cautious. We expect low growth and policy inaction to contribute to a deterioration in SA’s fiscal and debt metrics, inevitably leading to further moves into subinvestment grade territory and index exclusion if we see no immediate policy reaction. The hunt for yield in emerging markets has diverted attention away from this deterioration. But low global real rates may not last forever, and when the easy money stops flowing into the country, it will expose SA’s harsh reality. It is for this reason that we adopt a cautious approach when it comes to investing in the local bond market. A significant repricing of local bond yields would be required for us to invest. In the interim, we do see selective value in short-dated ILBs and the longer end of the government bond curve, which provide relative value in difficult times.