Quarterly Publication - October 2017

Airbus - October 2017

Few displays of human ingenuity and technological progress are more impressive than the commonplace sight of massive metallic tubes flying people largely safely and reliably into airports across the globe. Aircraft are complex machines that inspire awe in the observer, but when it comes to investing in companies that are involved in either building or operating them, the experience has not always been quite as rousing.

We have always approached investing in air travel with caution. Airbus was a case in point. While it has been on our radar for the last few years, its past as a state-controlled entity with low profitability, a heavy and at times poor investment rate, and governance failures had kept us on the sidelines.

The business was born in the late 1960s and is an amalgamation of various European aerospace and defence companies that were put together over time with the ultimate goal of creating a pan-European champion that would compete with its US counterparts in these strategically important industries. In its commercial aircraft division, the most significant part of its business – which now accounts for 75% of revenue, followed by defence and space with 16% and helicopters with 9% – Airbus reached technological parity with its key American competitor, Boeing, in the early 2000s.

While Airbus (then known as EADS) was listed on the Paris stock exchange in 2000, its full privatisation started in earnest in 2012 when its French, German and Spanish state-owned shareholders agreed to limit their aggregate holding to a maximum 30% of the shares outstanding. By that point, the business was an established duopolist (along with Boeing) in commercial aviation and commanded market share of some 50%.

After decades of outsized investment, it was finally allowed to focus more on commercial priorities. The newly promoted management team at the time signalled this shift in mentality by taking rational decisions relating to its commercial aircraft product cycle: it decided to launch updated versions of its current programmes (known as ‘re-enginings’ due to the application of a new, more capable engine on an aircraft body that was only slightly updated) rather than new, cleansheet designs. The main advantages of ‘re-enginings’ are that they are quicker to execute, carry lower technological risk – which is mainly borne by the engine makers instead of the aircraft manufacturers – and require significantly lower capital expenditure. Still, due to the long time lag in aviation between product launch and entry into service, the impact of these decisions will only start being evident at the end of this decade and even more so in the 2020s.

SECULAR GROWTH

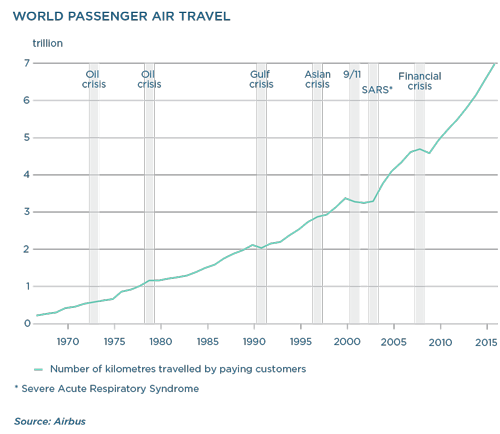

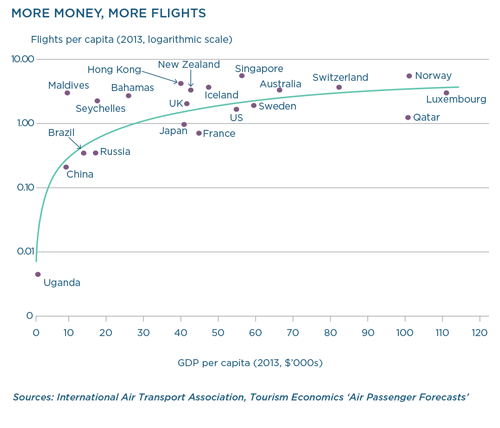

The most important external variable driving the Airbus commercial aircraft division’s long-term revenue growth is, of course, air travel. Ever since aviation became commercialised in the 1950s, air traffic has proven to be very resilient to external shocks. Wars, aviation disasters, natural phenomena, epidemics and economic crises have only temporarily stalled the growth in the number of annual air passengers. Air travel has recovered every time and has correlated well with the growth in countries’ GDP per capita (as is evident from the graph on the following page).

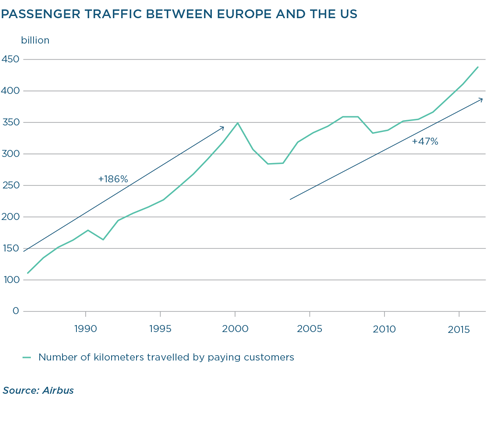

This resilience speaks to the strength of the human desire to explore the world and to maintain personal connections. In fact, it seems that the demand for travel is almost insatiable: markets such as Europe and the US have been deemed ‘mature’ for decades, but keep growing at a reasonable pace as air travel frequency continues to increase.

The best example to illustrate this is the busy North Atlantic air travel market. Unlike other categories where structural growth subsides within a couple of decades, it is hard to imagine an end to air traffic growth in this century.

BACKLOG AND PROFITABILITY

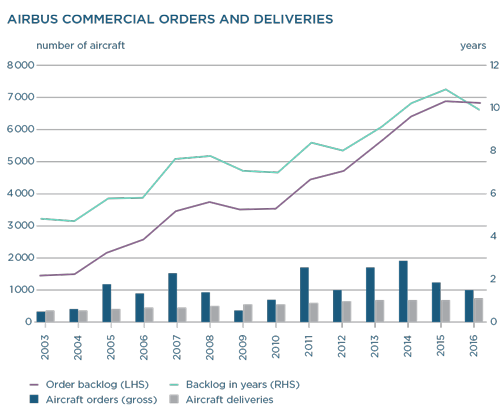

In order to meet the global demand for aircraft, Airbus has been steadily increasing its production capacity. Backed by a very strong order backlog (worth almost 10 years of production at current production rates), the company is adding to its product suite and upgrading some of its current bestsellers. Still, its current earnings are abnormally low. This is due to the development of three new programmes, the A350, A320neo and A330neo. Airbus uses the cost accounting method to compile its financial statements, unlike Boeing which relies on ‘programme accounting’. Airbus incurs the upfront launch costs of a new aircraft programme before the corresponding sales ultimately more than offset these costs over the programme’s lifespan of 25 to 30 years. As the A350, A320neo and A330neo programmes mature, they will not only boost the revenue line, but also reverse the dampening effect they have on profitability and strongly improve free cash flow generation.

On top of this, the company's bottom line is currently affected by currency hedges. Its currency exposure is hedged out for many years in the future, and as a result of the weaker euro, maturing hedges have been expiring in the red. Over time, as hedges unwind, the business should benefit from any US dollar strength: the majority of its revenue is denominated in dollar, while a significant percentage of costs is linked to the euro and the British pound.

RISKS

The A400M military transport aircraft programme has been a problematic remnant from the ‘old Airbus’ era. The company has had to budget provisions of more than €6 billion in aggregate due to cost overruns and capability shortfalls. The resolution of the aircraft’s woes depends on sensitive negotiations between Airbus management and government customers that could take longer than is currently anticipated.

Naturally, the global business cycle will affect aircraft demand (as well as military and helicopter orders), but we believe its large order backlog should insulate Airbus from sharp cyclicality. Moreover, barriers to entry are high: new aircraft from competing manufacturers – Chinese and Russian in particular – appear at least 10 to 15 years away from becoming credible, commercial alternatives to the duopoly’s products.

Although governance has improved materially in the last few years, Airbus faces outstanding investigations on alleged past transgressions. If these were to result in fines, we believe Airbus has the balance sheet to withstand them comfortably. We take governance into account when deciding on the quality of a business and we incorporate our view into the fair value multiple we assign to the company.

VALUATION

The stock trades on 18.5 times its expected 2018 earnings, which may seem like a rich multiple to pay for a European industrial. However, we believe the current price only partially discounts the profitability improvements that Airbus should deliver by the end of the decade, and almost completely ignores a second leg of profit uptick in 2020 to 2025 as new aircraft programmes enter maturity.

Accordingly, Airbus recently became a holding in our Global Emerging Markets Equity and Global Equity (developed market) portfolios. The stock is eligible for both international strategies, as Airbus has more than 55% exposure to emerging markets, both by revenue and by its order book. This is the result of the rise of Middle Eastern carriers and the growth of the Asian middle classes, which have shifted global aviation eastward and increasingly towards emerging markets.

Commercial aircraft manufacturers are investments with very long cycles. In our view, this gives long-term investors such as ourselves an edge. We are able to look at a company’s earnings and free cash flow generation potential many years out – key to appreciate the value we believe lies in Airbus.

This article is for informational purposes and should not be taken as a recommendation to purchase any individual securities. The companies mentioned herein are currently held in Coronation managed strategies, however, Coronation closely monitors its positions and may make changes to investment strategies at any time. If a company’s underlying fundamentals or valuation measures change, Coronation will re-evaluate its position and may sell part or all of its position. There is no guarantee that, should market conditions repeat, the abovementioned companies will perform in the same way in the future. There is no guarantee that the opinions expressed herein will be valid beyond the date of this presentation. There can be no assurance that a strategy will continue to hold the same position in companies described herein.