Quarterly Publication - October 2017

SA on the brink - October 2017

The SA economy might grow by 0.7% this year. If we are lucky. The numbers tell us that there has been very little spending by households, whose incomes are under pressure, and no-one is investing.

The real story is more complicated. Households’ incomes are stagnating because there has been no employment growth, and while inflation is more subdued, it has not compensated for a bigger tax burden. Consumers who can afford to spend have not done so because confidence has plummeted. Investment has not grown because government has an expenditure cap, and its revenues have disappointed. Companies have not invested because profitability has been poor and they, too, are worried about the economy. The latest business confidence data from the Bureau for Economic Research (BER) suggest that 65% of respondents think current conditions are unfavourable.

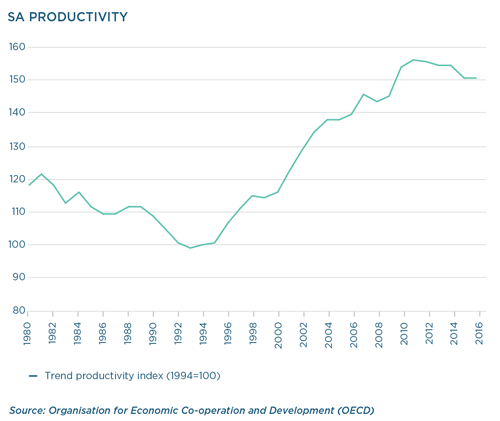

There are only three things that make economies grow: absorbing more labour (creating jobs), investing in better infrastructure (creating capacity) and combining the employed labour and better infrastructure in more productive ways (total factor productivity). These seemingly simple requirements are inherently enormously complex, and rely on an implicit fabric of socioeconomic and political stability, predictability, governance, ingenuity, education and time.

Where does government fit in? Government’s job is not to make economies grow; its job is to implement policies which enable the private sector to invest in growth. These include creating and reinforcing institutions which facilitate, educate, oversee, regulate, implement and police economic and social policies. In practice, the impact of government on the economy is much more complex. Feedback loops between policies and their economic translation often have unintended or unanticipated consequences. Often, it is not even policy, but a lack of policy that can have a damaging impact on the economy. A failure of confidence can have long-lasting and far-reaching repercussions.

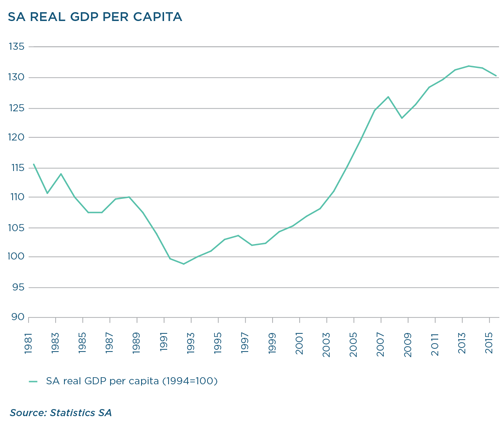

This gives us a framework within which to assess the way in which the economy has grown and evolved since democracy, and a way of articulating some of the challenges we now face. The graph below is the best illustration, showing real per capita GDP since the run-up to democracy, and three distinct periods of post-democracy growth.

1994 – 2001

In 1994, the ANC inherited an economy that was almost bust. Per capita GDP growth had been contracting in real terms for more than a decade amid international sanctions and a collapse in private investment, with an apartheid government which scrambled to create capacity which the private sector would not. The government deficit ballooned to -7.1% of GDP in 1993, and by 1996 debt accumulated to 48.2% of GDP. Inflation surged.

The incoming government liberalised and simplified internal institutions (abolished trade boards and subsidies, etc.), opened up trade with the rest of the world, implemented a new economic framework and initiated a fiscal reform programme (which included the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework budgeting process) to ensure transparency and improve participation. The economy benefited enormously from resurging confidence. Investment boosted productivity and potential growth estimates were revised higher to 3.6%¹.

Still, the period was not plain sailing … The Tequila Crisis in 1995, as well as meltdowns in Asia (1997) and Russia (1998) all rocked SA’s fragile markets and saw growth contract. With few fiscal resources and a central bank with a flexible mandate, the main policy rate surged to 21.85% in September 1998, the currency plummeted and higher inflation followed, peaking at 9.3% year on year in November of that year.

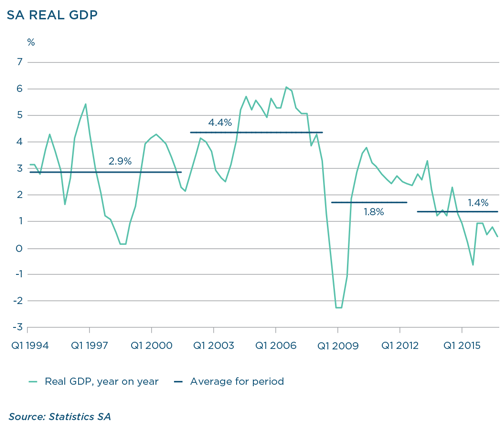

The official implementation of the inflation target from 2000 provided greater transparency and stability to monetary policy. During this time, real GDP averaged, with some volatility, at 2.9%.

2002 – 2009

The 2001/2002 currency crisis led to a spike in inflation and prompted the recently inflation-targeting central bank to raise the repo rate from 13% in September 2001 to 17% a year later. But the weaker currency boosted competitiveness and manufacturing output surged in a world where global growth was accelerating. The modern rise of China in turn raised commodity prices and was the catalyst for a multi-year boost to domestic terms of trade. As SA’s growth momentum increased, job creation improved, credit was extended to a wider proportion of the populace and a combination of conservative budgeting and upside surprises to nominal GDP facilitated a healthy dose of fiscal healing. Gross government debt fell steadily from its 1996 peak to 26% of GDP in March 2009 as the primary deficit moved into surplus. Growth during this period averaged a robust 4.4%.

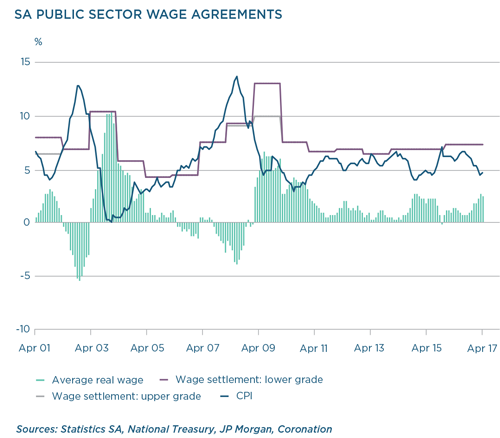

By 2009 government implemented textbook-true countercyclical fiscal policy in response to collapsing growth amid the global financial crisis. Government expenditure surged from 28.7% of GDP in 2008 to 33% by 2016 ... and then did not budge. Much of the increase went to a massive expansion of the government wage bill as the state’s employment rose from 24% of total employment in 2008 to 27%. On top of hiring, civil servants were awarded large employmentadjusted real increases. The massive increase in government employment further boosted the last driver of domestic growth – an accelerated emergence of the middle class.

2009 TO DATE

After an initial recovery (real GDP growth reached about 1.8%), growth has slowed steadily since 2012, averaging 1.4% since that time, but clearly slowing more recently. An absence of sustainable drivers in a weak global economy offers some explanation, as do idiosyncratic domestic events, including a rise in strike activity in 2012 to 2014, a crisis in electricity provision and the drought in 2015/2016. Still, the malaise has persisted even as these factors subsided.

A closer look at the data offers some clues: both household spending and overall capital expenditure have contributed less than before. Households have been under pressure from slow employment growth, spikes in inflation and a growing tax burden. Businesses have scaled down investment in capacity because global growth has been poor, compounded by a weak domestic economy. The most distressing reality though is that confidence levels of both businesses and consumers have tumbled to levels not seen since the early 1990s.

Businesses specifically have cited political uncertainty as a key constraint on investment in the BER’s business confidence survey. Households think future domestic economic conditions will be worse than today. This combination of low employment growth and poor capacity expansion (in SA’s case, this has fallen below capital replacement) has led to lower productivity and a significant deterioration in our estimated potential growth rate. The latest SA Reserve Bank assessment calculates this at about 1.1% for this year.

SA has few levers to pull to generate higher growth: the ‘democratic dividend’ is certainly a thing of our past; a helpful upswing in global GDP will help, but the kind of boost from terms of trade which facilitated employment and investment before is unlikely in a world of high leverage and excess capacity. SA’s own middle class could help, but only if employment, education and confidence improve. In short, we have no low-hanging fruit. Growth from here will require focus, commitment and a meeting of minds that are currently very far apart.

Much hinges on the political outcome of the ANC elective conference in December. There is a huge amount of guesswork, branch counting and slate speculation about the combination of candidates who may be elected to the National Executive Committee, and importantly, the ‘Top Six’. I honestly do not know what the outcome will be. I do know that a continuation of the status quo – the blatant theft, state capture without recourse and utter incompetence at strategic state institutions – is likely to reinforce the domestic constraints on growth. With this comes lower credit ratings, a weaker currency, probably higher interest rates and certainly fewer fiscal options as government finances continue to deteriorate. Still, assuming that this is the only outcome may be risky. Much has changed – the exposure of graft may constrain future fraud and public awareness makes legal recourse more likely.

SA has been on the brink before. Maybe the challenge is bigger and the rot more ingrained. Maybe not.

Importantly, there are people willing to do the ‘right’ thing, possibly even with their branch vote. A small shift in the leadership outcome could make a great deal of difference to key institutions, strategic ministries and regulators. Perhaps most important of all, some indication that politics in SA have shifted will reopen communication between the private sector and government, lifting very depressed confidence and opening the door, even just a crack, for better growth outcomes than seem possible now.

[¹] N Ehlers, L Mboji and M. Smal, “The pace of potential output growth in the South African economy”, South African Reserve Bank Working Paper, Research Department. March 2013