Investment views

Are you not entertained?

How sports content (and fast cars) became frontrunners in the media content race

- How audiences consume content has changed dramatically, and producers are in a fierce battle for viewership.

- The diversity of channels has made it harder for producers to monetise content.

- The exception is sports content for various reasons, including that most people prefer to watch it real time.

- Formula 1 has listed, making it the only truly global sporting franchise that provides investors with access to a top sporting event.

THE REALISATION THAT people attach a great deal of importance to being entertained is not a new one. One of the earliest observations dates back to first-century Rome, when the poet Juvenal decried the ‘bread and circuses’ used by government to pacify and distract the common man as he was slowly robbed of his democracy. In those days, the ‘circuses’ were the extravagant games put on in coliseums featuring violent, sometimes fatal, bouts between gladiators. Thankfully, much has changed since the days of Ancient Rome, but one thing that has endured is our collective love of being entertained – humans have always loved stories and escapism.

What has, however, changed dramatically over the intervening centuries is the media we use to consume those stories, particularly over the past 100 years or so. That change has not been a steady and cumulative force; rather, there have been long periods of relative stability punctuated by the arrival of a new technology that subsequently disrupted and radically reshaped consumption habits. The arrival of newspapers in the 1700s, cinema and radio in the early 1900s, TV in the 1920s and cable TV in the 1950s all fundamentally changed the media landscape.

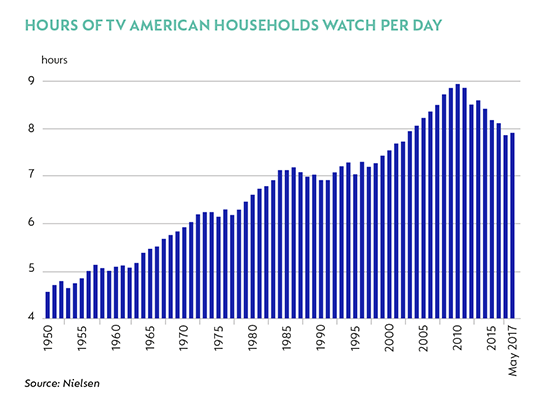

For many decades and the entire latter half of the 20th century, TV was a dominant and pervasive form of entertainment. The amount of time the average American household spent watching TV steadily increased after its mass adoption after World War II, reaching a peak of almost nine hours per day in around 2010. Since then, this number has been declining.

WHAT HAS CHANGED?

How we consume our entertainment is undergoing another tectonic shift, this time brought about by the advent of the internet in the 1990s and the smartphone in the 2000s. This was accelerated by the spread of broadband access and the consequent dramatic decline in the cost of downloading data and rapid rise in download speeds.

Consumers today now enjoy a near tyranny of choice when it comes to how to entertain themselves. The fact that traditional TV viewership is declining does not mean that those missing hours are not being spent on entertainment, but there has been a shift in how people are choosing to allocate their entertainment hours.

Estimates vary, but the average American adult spends more than three hours per day using a smartphone, double the amount of time spent a decade ago. A large proportion of this is spent on web browsing, social media, games or other forms of non-video content. But much is also being allocated to the likes of YouTube, Netflix and other providers of on-demand video content.

THE RACE FOR VIEWERS

The net effect is that the consumption of video entertainment in the US is not declining, but growing. And it is also growing strongly globally. A recent white paper by Cisco (a US maker of IT hardware used to transmit data over computer networks) estimated that global internet traffic has grown by 23 times over the past decade and will triple by 2022. By then, over 80% of this data is likely to be in the form of video content (up from 75% in 2017) and half will be consumed on smartphones and tablets (up from 23% in 2017).

What does this all mean? The global media landscape is shifting dramatically, given the changes in consumer viewing habits that are being enabled by new technology and new players. The creators of video content and the traditional pay-TV distributors of that content are facing increasing competition for eyeballs (as well as so-called ‘cord-cutting’ from consumers cancelling their service) from new ‘over-the-top’ (OTT) players like Netflix, Apple TV, Amazon Prime Video and Hulu that offer video-on-demand (VOD) over the internet.

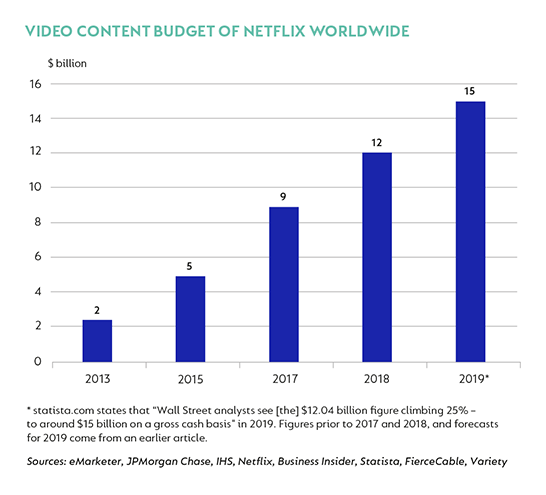

But these new players now find themselves in a content ‘arms race’ and they are spending vast sums of money on creating new video content to establish a beachhead in this new world. Netflix is expected to spend $15 billion this year on original video content, up from only $2 billion six years ago; Apple is aiming to spend at least $1 billion on original content ahead of launching its own OTT service; and Amazon is likely to spend $7 billion this year, up from $5 billion last year.

All of this is great for consumers who now have more choice of what to watch (the number of scripted TV shows in the US has more than doubled since 2010), where to watch it (on TV, internet-enabled TV, smartphone or tablet) and when to watch it. This last point is worth noting for an important reason: the rise of video streaming over the internet intensifies what the pay-TV distributors started years ago with the introduction of VOD technology, namely a reduction in the proportion of TV that is watched live. This means that viewers are now less likely to sit through advertisements, which makes video content less attractive to advertisers.

NOT ALL CONTENT IS EQUAL

There is an adage in the media industry that ‘content is king’. But this proliferation of original video content available on-demand makes it more challenging for content creators and distributors to capture large audiences and monetise their content. There is one notable exception, however: sports content is hugely valuable and becoming increasingly so.

In the US, the fee that pay-TV distributors are charged by ESPN (the largest sports channel) to include it in their offering is around four times that of the next highest fee channel. And channels like ESPN pay sports leagues increasingly large amounts of money for the rights to broadcast their games. For example, National Football League (NFL) broadcast rights have risen by roughly five times over the past two decades (well ahead of nominal GDP growth).

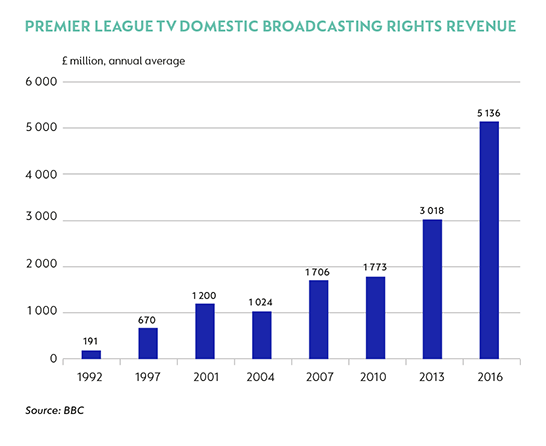

This is not only a US phenomenon: the domestic broadcast rights for the English Premier League have risen by 27 times in 25 years, and the tech giants are also starting to compete aggressively for sports rights. Last year, Amazon renewed a deal with the NFL for the rights to stream 11 of its games for $65 million per year – 30% more than Amazon paid for the same rights in the previous season, driven by fierce competition from its rivals Twitter and YouTube, and almost seven times what Twitter paid for these rights in 2016.

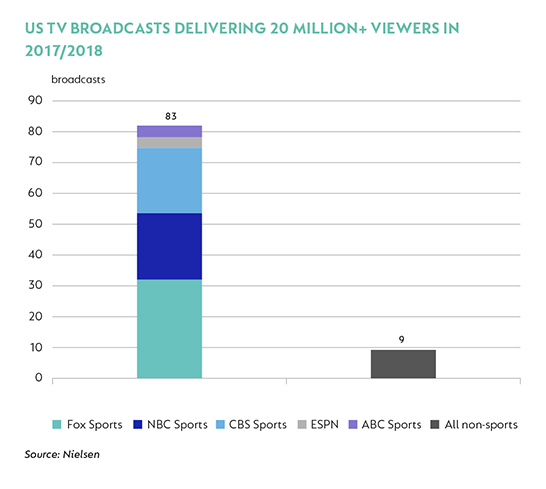

Sports content is attractive for a few reasons. The first is that people (increasingly) love watching sports. In 1998, 25% of the top 100 traditional TV broadcasts in the US were sports events; in 2018 this figure grew to 88%. Second, at the risk of stating the obvious, no new major sports are being invented. Unlike other forms of entertainment, such as TV shows or movies, someone cannot set up a new sport and churn out content to compete with existing sports. Third, most of the world’s big sports have well-established leagues and it is nearly impossible to start a new league that can compete.

This means that the supply of sports content has constraints and is relatively limited versus most other forms of content. Finally, most sports are watched live: sports are viewed live more than 95% of the time versus less than 50% for regular non-sports traditional TV content. What this boils down to is that sports draw large, live audiences who are willing to pay to view them, and thus are highly engaged, making sporting events attractive to advertisers. This is certainly a compelling option in an increasingly fragmented and competitive media landscape. As investors, it would be great if we could capitalise on this.

THE FORMULA FOR SUCCESS?

Unfortunately, there are few options available to investors in public markets to invest in sports content. There are a few publicly listed football teams such as Manchester United and Juventus, but the real owners of sports content (and hence the broadcast rights to that content) are the leagues themselves; there is a limited number of global sports leagues and even fewer that are directly investable. For example, one cannot buy shares in the FIFA World Cup or the Olympics, as they are not listed or private entities, but rather not-for profit organisations. However, fairly recently, one truly global sport has been listed and is now investable: Formula One (F1).

In January 2017, Liberty Media Corporation acquired 100% ownership of the then privately-owned parent company of the F1 Group, which holds the commercial rights to the sport of F1 for the next 90-odd years. The F1 Group was subsequently listed and now trades on the US stock market. F1 is the premier global motorsport series, with a long history and almost 500 million unique viewers in nearly 200 territories watching 10 teams fight it out in around 20 races across five continents every year. F1 is arguably the only global sports league or event other than the Olympics and the FIFA World Cup, but a noteworthy difference is that, unlike the Olympics and the World Cup, F1 happens every year.

PRICED OUT

F1 makes most of its money from broadcasting rights and the fees it collects from race hosts (each roughly one third of its revenue), with the rest coming from sponsorship deals, merchandising, licensing its intellectual property and a few other smaller items. On the cost side, F1’s largest cost of doing business is by far the roughly half of its revenue that it pays to the race teams. Fielding an F1 race team is horrendously expensive – there are no budget caps in the sport and so there is an incentive to spend as much as possible to create the fastest car possible to improve one’s chances of winning.

A mid-tier race team is estimated to spend roughly $150 million per season, while top teams like Ferrari and Mercedes likely spend as much as three times that amount. This means that despite the F1 league paying $1 billion of its revenue over to the race teams every year, most, if not all, teams are loss-making. The high cost of competing makes many teams unsustainable (since the first F1 race in 1950, over 150 race teams have come and gone), deters even large automakers from entering the sport and can make for duller racing on the track as deep-pocketed teams simply outspend the rest of the field.

DRIVING EFFICIENCY

There is reason to be optimistic that the new managers of F1 can better monetise the sport and, potentially, reduce how much revenue flows to the teams. For example, on a per-viewer basis, F1 earns $1 in broadcast rights for every $5 the NFL makes and every $3 the English Premier League earns. There is also room for improvement on sponsorships: when Liberty took over, only 13 of the races had title sponsors and F1 had only nine official partners (versus 47 for the PGA, 34 for the Olympics and 33 for the NFL).

On the cost side, although perhaps easier said than done, if Liberty can successfully negotiate better cost controls, it will improve team economics, increase how much profit it can retain, and possibly even make for a better racing spectacle by creating a more level playing field. Liberty is currently in negotiations with the race teams to make this happen and has some capable people in its ranks working on it.

Beyond this, Liberty is focused on growing awareness of the sport, including a recent 10-episode Netflix documentary and investing in an F1 esports series. After declining in recent years, F1’s global viewership rose by 10% last year. A standalone F1 OTT product is also being rolled out to monetise hardcore fans.

F1 is a very rare and iconic asset, and one of the most watched events on the planet. As an investment, it is a way to capitalise on the heightened competitive environment and demand for sports content discussed above, while also offering levers that can be pulled by F1’s management to improve the sport and strongly grow its revenue and profits. We recently took a position in the F1 Group in our Global Equity Strategy on behalf of our clients. Like the Ancient Romans did with theirs, we will be watching the F1 circus closely.

United States - Institutional

United States - Institutional