Quarterly Publication - October 2017

Europe's Reprieve - October 2017

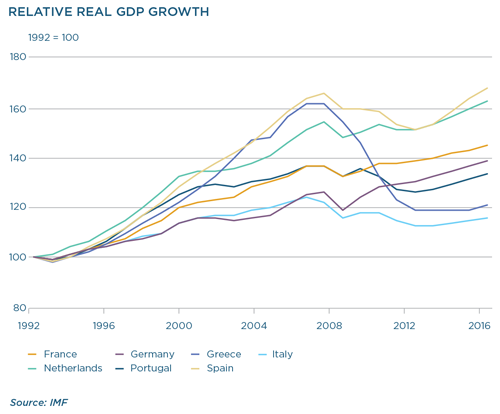

Europe has been the big surprise this year. Reeling from the unexpected decision by the UK to leave the EU, and Donald Trump’s election win in 2016, it was hard not to expect a populist victory in a vulnerable Europe in 2017. Many in Europe have suffered deeply during a decade of slow recovery, and economic hardship has contributed to political outrage, especially against outsiders. Concern about populism was even more pronounced because the global financial crisis, followed by the Eurozone sovereign debt and banking crises, had already triggered a crisis of confidence in the EU and its monetary union. Against this background there was very real concern that the emergence of populist political parties would be the death knell for a weakened Europe.

In Europe, populist parties on both sides of the spectrum have been more visible, more vocal and perhaps more entrenched than in either the US or the UK. The election calendar in 2017 was also unusually packed, with each country’s own populist politicians proposing various, and sometimes extreme, alternatives to the status quo. Still, most offered a common anti-immigration narrative, forcing centrists to adopt it as an electoral issue. The economic implications seemed bleak. And as the polls ahead of the Brexit vote and US election were so misleading, nervousness grew about an adverse outcome in at least one of the elections.

ELECTION RESULTS

The first key European country to hold elections this year was the Netherlands. It has a rather complex electoral system which allows for a broad level of representation in the Binnenhof. Coalitions are common, and it seemed unlikely that populist firebrand Geert Wilders of the Party for Freedom (PVV) would gain a ruling majority. Nonetheless, his strong views on immigration were widely telegraphed, especially since the Netherlands is traditionally one of the more tolerant EU members. Wilders’ campaign called primarily for the de-Islamification of the Netherlands and more sovereign independence, “including from the EU”. On the day, the PVV gained the second-most votes, but failed to attract a meaningful coalition partner.

The elections in France were perhaps the most important and least certain. Emmanuel Macron, running as an independent, campaigned for wide-ranging economic reform and a strengthening of relations with the EU. The campaign of the Republican nominee, François Fillon, was plagued by controversy. But their challenger, the established anti-EU populist Marine le Pen, remained consistently popular in the run-up to the election. Macron’s victory not only secured him the presidency, but his new party, La République En Marche, gained the parliamentary majority. A resounding victory for French Europhiles, with a mandate for muchneeded labour reform within France.

It was supposed to be the most predictable election of the year that ultimately sprung the biggest surprise. The outcome in Germany confirmed that Europe has only seen a political reprieve and not resounding support for moderate politics. As expected, Chancellor Merkel won her fourth term, but there was a significant shift in underlying political dynamics. Instead of a Grand Coalition, Merkel will have to rebuild her coalition with liberal alliances. There is also now a blemish on the political landscape with a swing in support towards the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD). Again, centrist candidates lost support due to immigration concerns.

While the electorate supported European unity, it is clear that deep divisions remain, specifically regarding immigration and fiscal union, and these are close to the surface. Nonetheless, diminished political risk, surprisingly strong European growth momentum, recovering labour markets and a supportive global context are serving a potent cocktail for Europe.

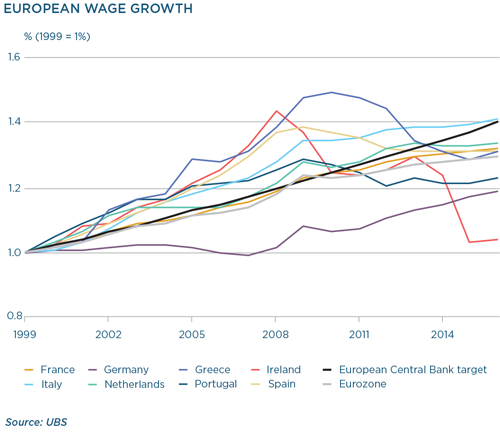

GDP growth may remain comfortably above 2% this year, and is expected to stay at about the same rate in 2018. With unemployment in Europe (currently 9.1%) at multi-year lows and further support for a tightening labour market, there may be a cyclical opportunity to integrate further, to bring Europe from an “imperfect monetary union to a true economic continent” (according to the French finance minister Bruno Le Maire). But the opportunity is more likely to be a window than a door.

EUROPE’S OPEN FLANKS

The path to closer European integration is full of obstacles, on all flanks:

Economic flank: closer fiscal union

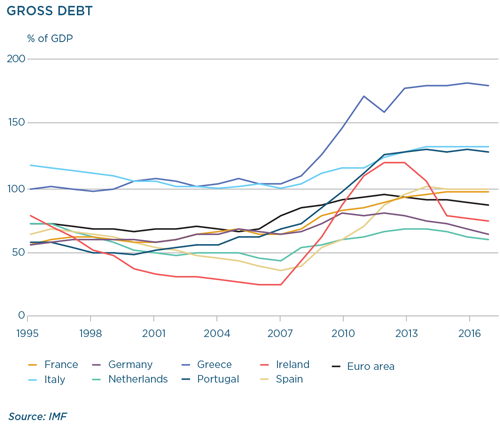

This is arguably the biggest risk factor for the EU. The current monetary union lacks key features crucial for longterm stability, above all greater fiscal union at a centralised level. Members have given up their exchange rates, but the failure to further unify their fiscal policies has weakened the union’s ability to react to shocks. Unfortunately its most powerful (and fiscally conservative) members have weakened the move towards a sufficient centralised fiscal policy. Without it, the EU remains hamstrung in tackling future challenges.

Political flank: immigration

The immigration crisis of 2015 revealed that Europe fundamentally disagrees on immigration politics, which has emerged as a poisonous and divisive political narrative.

No unified vision for Europe

The aforementioned economic and political weaknesses are compounded by a lack of common vision. This, in turn, has led to the emergence of political alternatives in Hungary and Poland that have been moving very far away from the political centre. A new agenda needs to provide potential areas of cooperation, to ensure focus and build momentum.

CONTINENTAL DIVIDE

A first step in rebuilding the European project is recognising the deepening divisions, inequality and ongoing economic hardship following the global financial and European crises. This has undermined trust in EU institutions, threatening the broader European identity and terminating integration efforts. Countries which had to be bailed out have suffered slow and painful economic transitions. The process has deepened the North-South economic and political divisions, and reinforced the dominance of the stronger countries in institutions and policymaking. Externally, immigration, terror threats and attacks, a re-emergence of national identity and concerns about East-West geopolitical uncertainty all challenge the existing framework.

Germany, the biggest economy within the EU, has benefited enormously from conservative policies in the period between 2002 and 2009, especially in the labour market, and after that from the weaker euro. Germany is running a current account surplus at a breathtaking 8.6% of GDP (at the end of 2016), and growing at 2.1% year on year, above its estimated long-term potential. Germany has low government debt to GDP (65%) and is running a small fiscal surplus. It also has the loudest voice in EU decisionmaking.

France’s position has been largely overshadowed by Germany, but regional momentum and revived hope of reform and stronger growth have boosted its GDP to 1.8% year on year. France’s debt levels are high at 96% of GDP, and its deficit is persistent at -2.8%. But for the first time in years, French confidence is on firmer ground and Macron has a very real opportunity to reinvigorate the economy. Credible domestic reform will also boost France’s ability to promote a reform agenda to Europe.

The so-called ‘European periphery’ – Ireland, Spain, Portugal and black-sheep Greece – saw their domestic financial systems buckle under massive debt burdens. In Ireland and Spain, private debt and poorly regulated banking systems were the root cause, while in Portugal and Greece profligate fiscal policy during the boom saw deficits bulge and debt rise. All suffered ballooning current account deficits as debt increased. As the crisis hit these vulnerable economies, the bailout of the banking systems led to a sharp rise in an already large stock of debt. All four sought financial assistance.

Through a painful adjustment, Ireland exited its reform programme, and has managed to recover. The other three are taking longer to recuperate. Still, economic stability in Spain has improved meaningfully, and Portugal too is on a firmer footing. In Greece, the fiscal interventions required to stabilise the sheer burden of its debt has left the economy in an almost semipermanent recession. The situation has become so dire that eight years into its reform programme and seven prime ministers later, the EU and IMF are at loggerheads about how to proceed. The IMF is advocating debt relief for Greece, while the EU, which has already lowered debt service and extended the repayment periods for Greek debt, is reluctant to do more.

THE WAY AHEAD

At this stage, France offers the best options for a new integration agenda. France’s proposal, presented by Macron at the Sorbonne in late September – after the German election – stated explicitly the need for Europe to consolidate against the present threat of populism. Macron called for “the refoundation of a sovereign, united and democratic Europe”. Amongst his wide-ranging proposals were a bigger EU budget to fund investment and provide a cushion against shocks, a simplified European Commission, an EU intervention force with a unified frontier police force, educational initiatives across EU institutions, funding for innovative research and an overhaul of agricultural policy. He fell short of directly proposing a European Monetary Fund with oversight by a single finance minister , but has mooted these in the past. The importance of these proposals is twofold. France, by implementing tough reform at home is claiming its place as a significant driver of EU integration. Also, by offering a wide-ranging menu of reforms, Macron gives Europe options to choose a path forward.

Earlier this year, the European Commission released a report that called for more efficient economic structures, a financial union (including a banking union and a capital markets union), a fiscal union which will promote fiscal sustainability and stabilisation and, ultimately, a political union with democratic accountability, legitimacy and stronger institutions. The report sees these unions slowly evolving in parallel. However, it acknowledges that short-term measures need to be ambitious in order to be meaningful.

The challenge, as always, is getting it done. Of the bigger, more influential European economies, only France really has presidential commitment, with adequate domestic backing, to push the reform agenda. And that is not enough.

STRONGER TOGETHER

It is possible that economic reform in France will see a strong economic revival. President Macron has already implemented labour reform that will go a long way to addressing France’s economic malaise. In doing so he is supporting regional growth, boosting confidence, reinforcing credibility and creating a platform for a new debate on European integration.

But what Europe really needs is for Germany to set aside its fiscal conservatism and take responsibility for the union and the role it plays. It needs to make a bigger economic commitment to the stability of the EU. Unfortunately, Germany’s election outcome does not give much hope – despite the possibility of a more liberal, pro-Europe coalition, Germany remains fiscally conservative.

For many young Europeans, their only experience of being part of the EU has been miserable – high unemployment, fiscal constraints, poor wage growth, ongoing risk of economic crisis, banking fragility, systemic risk and external threats to their safety. There is a major risk that these voters opt out rather than integrate if nothing changes. Stronger economies may help counter the risk, but current growth will be put to the test soon: the next two years bring a host of fresh elections to the European calendar. If current growth falters, this optimism fades.

Global (excl USA) - Institutional

Global (excl USA) - Institutional