Financial Times, beyondbrics: Nigerian banks suffer in oil storm

27 January 2015 - Peter Leger

The following contribution by Peter Leger, Head of Global Frontier Markets, was published on the beyondbrics blog of the Financial Times on 27 January 2015.

So you thought a six-month break on a desert island looked appealing and spent long hours in silent meditation, reflecting on self-actualisation, harmony and humanity’s ceaseless race to consume the planet. Now you’ve just made the return journey to find that the oil price collapsed from over $110/barrel to less than $50. Peak theorists having turned into piqued theorists. You didn’t see that coming. And, frankly, neither did we. Nor did we expect to see the Swiss franc jump 28% – in a single day – as it did recently. The lesson being that extreme volatility has to be an assumption when building portfolios, and doubly so when investing in frontier markets, where volatility is often amplified.

For now, the main question is what an oil price that remains below $50 will mean for investments in Africa. We have good news and we have bad news.

First, the bad news. For Nigeria, oil at $50 is extremely challenging. And Nigeria tends to be large in any Africa fund out there. While Coronation’s Africa portfolios are significantly underweight in Nigeria (at around 20% of fund exposure), this is little consolation as that market is still very important to us. And while we have a naira currency hedge in place that helps dull the pain, some discomfort has been endured – with the risk of more to come. Why are we concerned?

Nigeria is an oil economy with very restrictive capital flows. To date, the exchange rate has been managed by the central bank, with a number of measures taken to control pressure on the currency, including a step-change weakening of the exchange rate. Restricting the ability to take capital out of the country in the hope that the oil price will recover is not a viable strategy. Our sense is that pressure is building and another step change in the exchange rate is likely. We have hedged 20% of our currency exposure and won’t consider removing this hedge despite the naira’s significant depreciation.

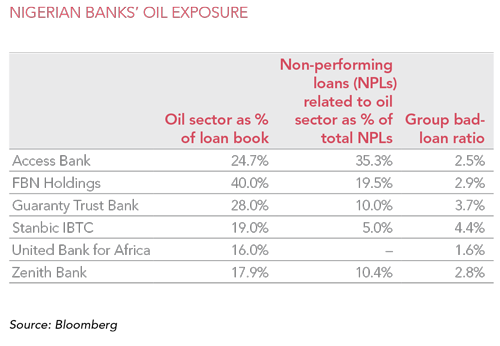

The Nigerian sector most at risk, other than oil companies themselves, is the banking sector. The banks’ total loan book exposure to the oil sector ranges from 17% to 40%. Yes, 40%. To make matters worse, the bank with 40% exposure (First Bank of Nigeria) has the largest loan book in Nigeria. Its exposure to the oil sector is double the central bank’s maximum limit (20%) allowed to any sector. Currently, bad debts in the oil sector are low, but we don’t believe that this will persist. And the very sharp drop in share prices over the last three months suggests that we are not alone.

The Nigerian banking sector’s over-reliance on oil is nothing new, and we have so often expressed our concerns about this distortion that our regular readers may be stifling yawns. We do, however, think that valuations have now sufficiently discounted a large amount of bad news and, with prices trading well below half of book value for a number of banks, this has us interested. There are many dynamics to consider. Firstly, a further risk of currency depreciation must be taken into account. Where will oil settle and for how long? Elections take place in February and are expected to be colourful. The banks’ books are in much better shape than during the crisis of 2009 due to stringent central bank controls. And, on the whole, banks are well capitalised, although regulations around this are tightening further, suggesting that equity will be issued at lower prices. But on balance, now would be the time to buy Nigerian banks, not sell them.

On to the good news. Some countries will benefit considerably from lower oil prices. Top of the Africa list is Egypt. An International Monetary Fund report in January 2013 shows that in 2011, Egypt’s energy subsidies were the largest in the emerging market universe, at over 10% of GDP. It has already started cutting energy subsidies and raising prices. This will go a long way to reducing the pressure on its finances. The likes of Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe will also benefit. This is significant as energy is a large component of spending in those countries.

Commodity markets tend to take longer than most markets to self-correct. Supply and demand dynamics are long in duration, and weather dislocations in prices for much longer than investors have the patience for. We have estimated a normalised price for oil of $78 a barrel for quite some time. Short-term prices look likely to drop further, but with time, market dynamics will be self-correcting. And with this, there are some very attractive returns to be made. Getting this one right will be a major differentiator, and we have to invest calmly through this storm. A return trip to that desert island might be just the thing.

Global (excl USA) - Institutional

Global (excl USA) - Institutional