Economic views

Recoupling, but on uneven terms

- A global economic outlook

The Quick Take

- Global growth is resilient but uneven as investment in AI and technology fails to boost the stagnant labour market, and tariff-related uncertainty remains

- The full impact of tariffs is yet to be felt by the US consumer, and we can expect households to come under more pressure in the months to come

- Political volatility is intensifying, threatening confidence, stability, and growth

- SA is off to a positive start with better-than-expected growth, contained inflation, and a strong rand, but risks remain

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The global economy enters 2026 at a sensitive inflexion point. Growth has proven to be unexpectedly resilient through one of the sharpest trade policy shocks in decades, yet the expansion is increasingly disconnected. Capital expenditure (capex) – narrowly concentrated in AI-linked technology – has accelerated, while labour demand has stalled. Inflation has fallen from post-pandemic peaks but remains stubbornly above target in much of the developed world. Fiscal policy is no longer tightening, but nor is it meaningfully expansionary at the global level. Monetary policy is easing, but towards neutral rather than stimulus.

This year will be about economic realignment – between capex and hiring, between output and income growth, and between growth and inflation dynamics. The risk is that this recoupling happens through slower growth rather than stronger labour markets. Asset prices are vulnerable to a correction. The opportunity is that policy support, easing financial conditions, and continued investment in AI allow the expansion to broaden without reigniting inflation.

Our base case is for global growth to experience a soft patch early in 2026, driven by weaker consumption dynamics in the US due to delayed tariff pass-through and weak real income growth. This will be followed by a modest re-acceleration in the second half of the year. In Europe, growth is set to accelerate as fiscal stimulus picks up pace, while Chinese activity is still heavily reliant on exports and vulnerable to weaker US consumer spending. The distribution of risks is wide, asymmetric, and increasingly political.

GLOBAL GROWTH: RESILIENT, BUT INCREASINGLY UNBALANCED

From shock absorption to fragility

Global growth held up better than expected in 2025, despite a dramatic escalation in US tariffs. In fact, 2025 marks the fourth consecutive year that global growth outcomes exceeded expectations, despite a series of shocks which would, historically, have led to weaker activity. These include a cost-of-living crisis, interest rate shocks, and a multidecade increase in tariffs. Global GDP growth looks set to average around 2.5%-3% in 2025, with a similar pace expected in 2026. That headline stability masks important shifts beneath the surface.

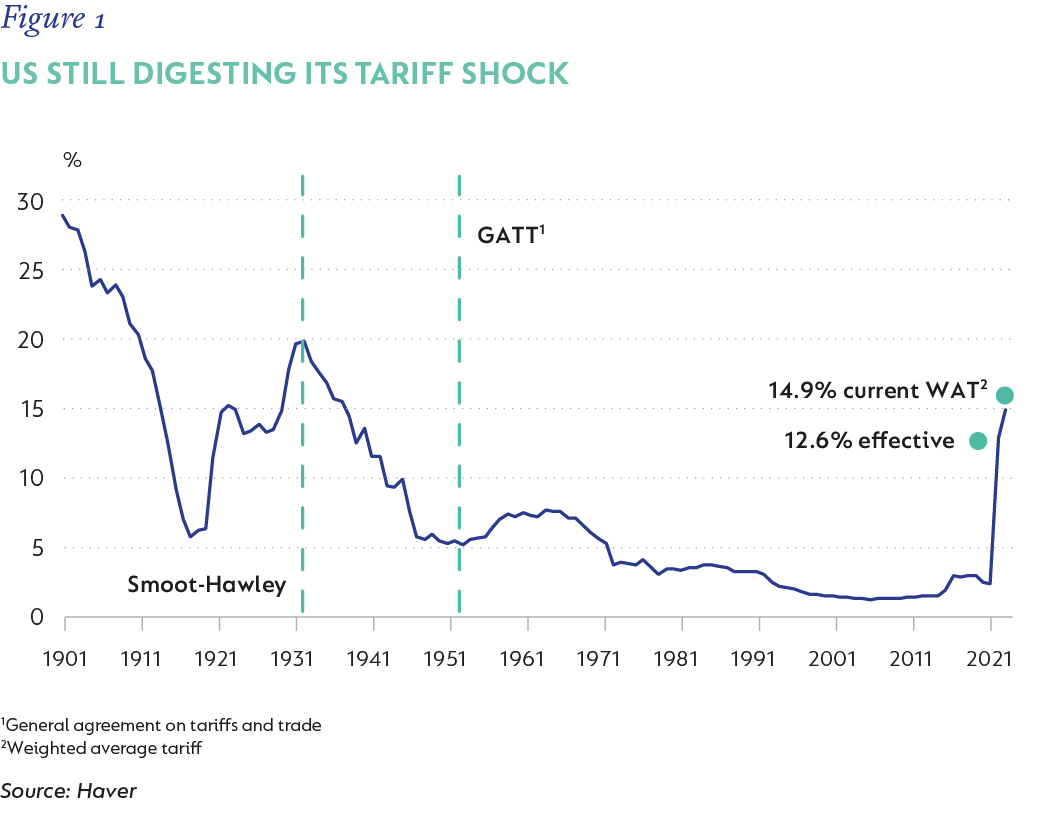

Part of the explanation lies in the delayed and diluted transmission of the 2 April Liberation Day trade shock (Figure 1). The near-term hit to activity was buffered by a combination of tariff exemptions, back-and-forth negotiations, US-Mexico-Canada Agreement compliance, a lack of broad retaliation, and corporate margin absorption. Successive front-loading of imports and investment further flattered growth in 2025. But this has also created a hangover risk for 2026, particularly in manufacturing (recent PMI data appears to confirm this dynamic). The full impact of the tariff shock is probably still to come.

The unusual decoupling: capex up, jobs down

One of the economic surprises of 2025 was a sharp acceleration in global business investment – driven almost entirely by technology. At the same time, developed-market employment growth practically stalled. Unfortunately, investment didn’t translate into improved labour market conditions; instead, labour markets have continued the downward trend.

The quality, or breadth, of growth matters. If weak hiring reflects temporary uncertainty, labour demand should improve as policy clarity improves, possibly supported by monetary easing and/or fiscal impulse.[1] If it reflects structural substitution away from labour (AI traction), income growth will lag output for longer, amplifying distributional and macro risks.

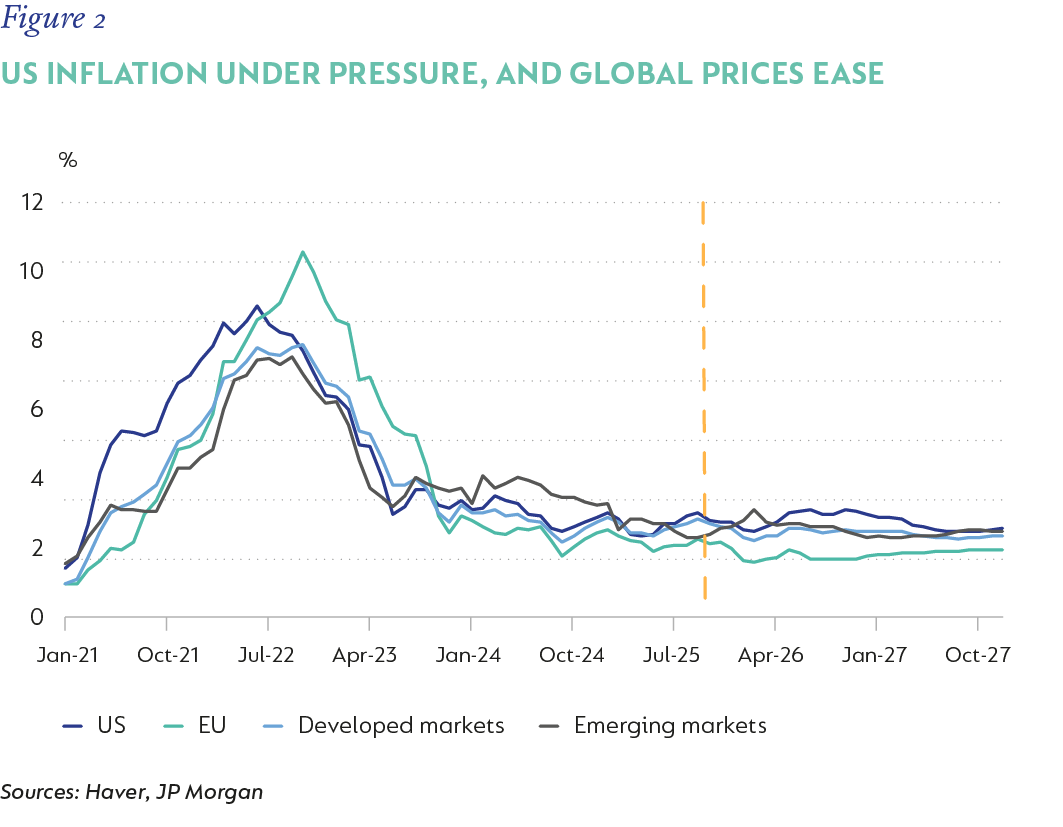

A global disinflation with US exceptions

Inflation has clearly turned the corner since 2022, but the last mile is proving difficult. Outside the US, headline and core inflation in much of the developed world is approaching target. Services inflation remains elevated, but forward-looking wage indicators suggest gradual normalisation through 2026. This would provide central banks in Europe and parts of the emerging market complex with room to ease, if necessary.

The US is the outlier. Tariffs have reopened a wedge between US inflation and that of its developed market peers (Figure 2). Data decomposition suggests that only a small proportion of the potential tariff impact has passed through to consumer prices, with companies absorbing much of the hit. A shift in this dynamic would see US core inflation remain at around 3% or higher through much of 2026.

The implication is not renewed inflation acceleration, but inflation persistence. This matters for policy reaction functions and real income dynamics, and could certainly see the Federal Reserve Board’s stance become more cautious.

In the UK, inflation has also been sticky, but a sharp deceleration in inflation in November opened the door for another rate cut by the Bank of England in December. Goods disinflation was the key driver, and, while this is likely to persist given strong Chinese export deflation, sticky wages are likely to balance the prospects for further policy easing.

MONETARY POLICY: EASING TOWARDS NEUTRAL, NOT STIMULUS

The end of restrictiveness

The global monetary cycle turned meaningfully in 2025. While further easing is expected in the year ahead, the uneven growth dynamics will render decisions highly data dependent in both developed and emerging markets. Overall, we see policy rates gliding towards neutral, not below it.

There is a wide divergence of views on the Federal Reserve. Our baseline is a further 25 basis points (bps) in easing, taking the upper limit to 3.5%. This will largely depend on labour market dynamics in the early part of 2026, but will likely be limited by inflation persistence and a relatively short-lived moderation in growth momentum.

Elsewhere, the picture is cleaner. In the EU, inflation is closer to target, and the case for neutral rates is stronger as growth is set to accelerate. Japan remains the exception, with rising inflation, a weak yen, and policy set to continue a gradual normalisation from decades of ultra-low interest rates.

FISCAL POLICY: SUPPORTIVE LOCALLY, NEUTRAL GLOBALLY

Front-loaded, not transformative

In aggregate, fiscal policy should shift from drag to mild support in 2026 – despite expansionary moves in key economies.

In the US, there is some near-term stimulus through tax cuts and shutdown reversals, but this is offset by State and local consolidation, fading industrial policy support, and tariff revenues that act as a tax on consumption (although there was a boost to coffers that helped in 2025).

Germany and Japan stand out for more meaningful fiscal easing. Germany’s planned fiscal stimulus is expected to add about 50bps to GDP growth over 2026 and 2027, as the implementation of both infrastructure and defence spending picks up. China continues to rely on targeted, front-loaded stimulus, although there are recent indicators that Beijing may expand targeted investment in priority sectors such as advanced manufacturing, technology, and education.

At this stage, though, the message is clear: fiscal policy will cushion the cycle, not drive it. Structural deficits are entrenched, and political constraints limit further expansion.

Debt dynamics and fiscal constraints

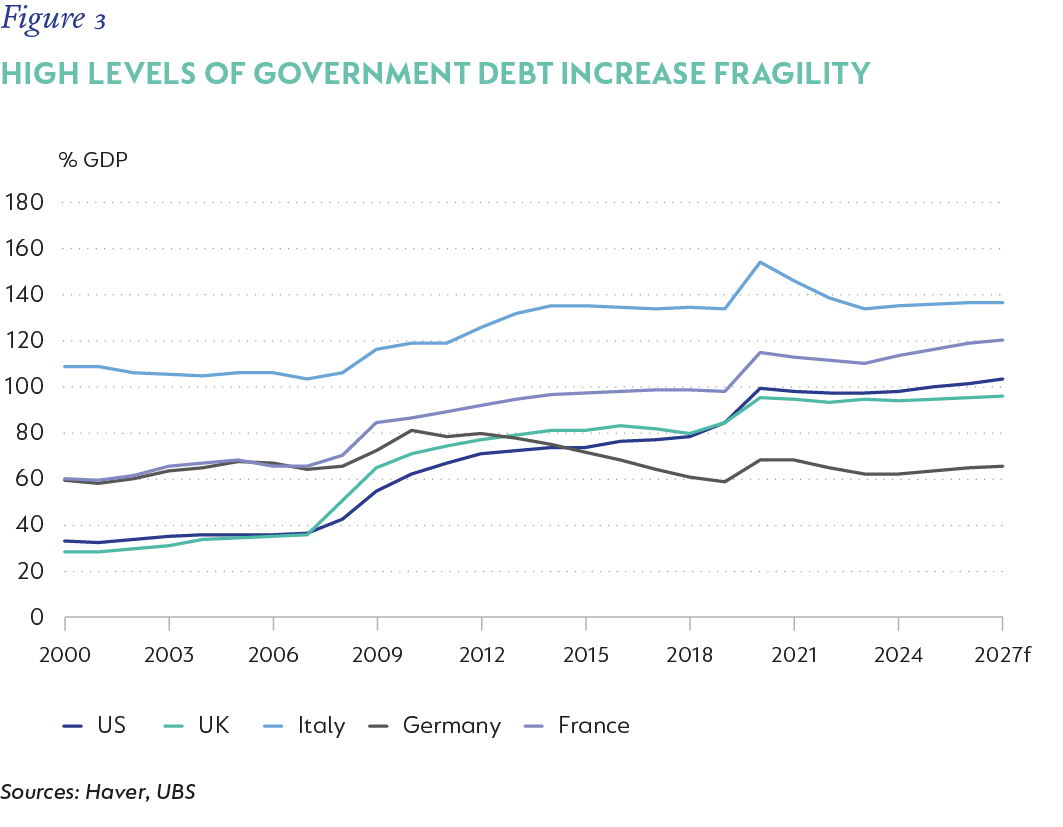

Global debt levels are elevated, and debt dynamics increasingly constrain fiscal headroom. Latest IMF data suggests global debt ‘stabilised’ at c. 235% of GDP, of which public debt accounted for 93%, in 2024.

There are strong divergences in debt dynamics between countries (Figure 3). The US position is vulnerable, and it is expected to run large headline and primary deficits for a long time. While growth remains resilient, rising interest rates have raised the cost of relatively short-term debt. US funding will remain high, which is likely to maintain pressure on yields. With large expenditure commitments, US debt is rising and leaves the fiscal position vulnerable.

Elsewhere, the risks vary: Italy has returned to its commitment of running primary surpluses, which should help stabilise debt, while Germany’s fiscal expansion will see its strong position deteriorate at the margin.

Taken together, high and rising global debt not only increases economic fragility; it also implies growing uncertainty about fiscal sustainability in key economies, which will keep pressure on risk premia in times of uncertainty.

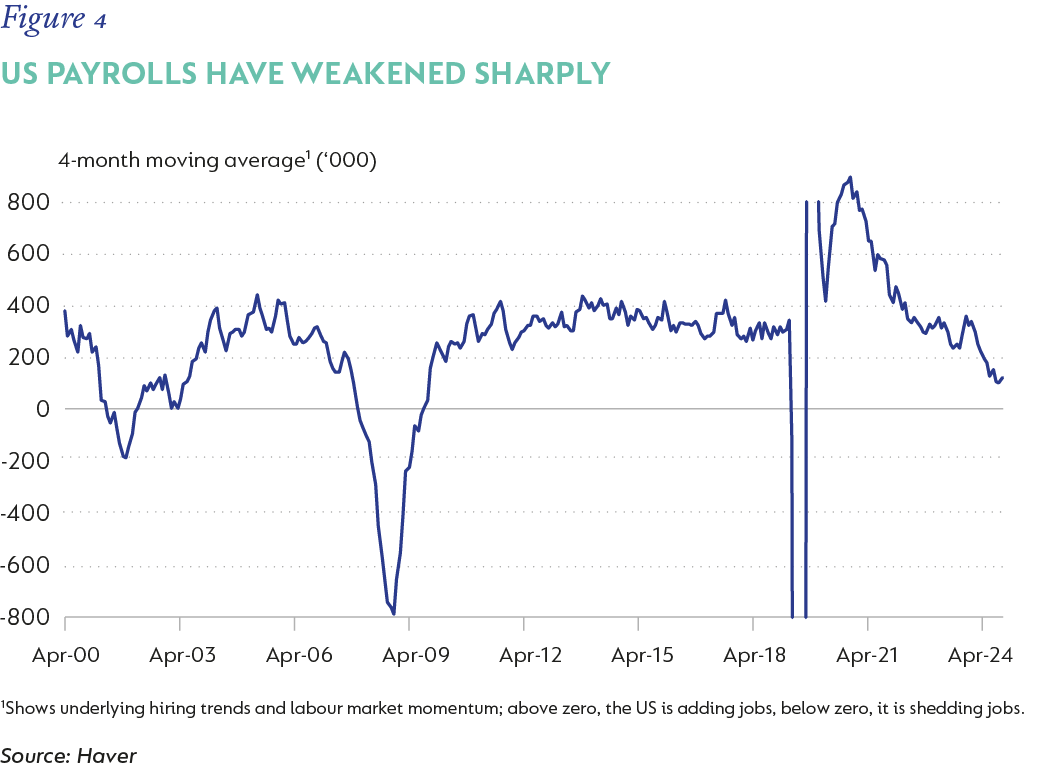

US labour markets and income: the fault line of 2026

The outlook for the US labour market will be pivotal for policy direction in 2026. Figure 4 illustrates that labour dynamics weakened throughout 2025, with job openings falling, payrolls slowing, and a 30bps uptick in the unemployment rate to end at 4.4%. While this ‘low-hire, low-fire’ dynamic held for much of the year, job cuts picked up in the fourth quarter.

It is possible that heightened uncertainty related to the impact of tariffs, AI, US policy, and political events kept businesses cautious and restrained with respect to investment and hiring. However, it is also possible that, as tariffs continue to impact the economy, household consumption may weaken. This would place renewed pressure on margins at a time when the underlying labour fundamentals are considerably weaker than a year ago.

The central question for 2026 is whether labour demand rebounds after a ‘soft patch’. If hiring picks up as fiscal and monetary support kicks in and uncertainty fades, income growth should stabilise, and the expansion can broaden. If not, the economy risks sliding into a low-confidence equilibrium with persistent inflation and weak demand.

RISKS: ECONOMICALLY ASYMMETRIC WITH HEIGHTENED POLITICAL UNCERTAINTY

Downside risks dominate the near term

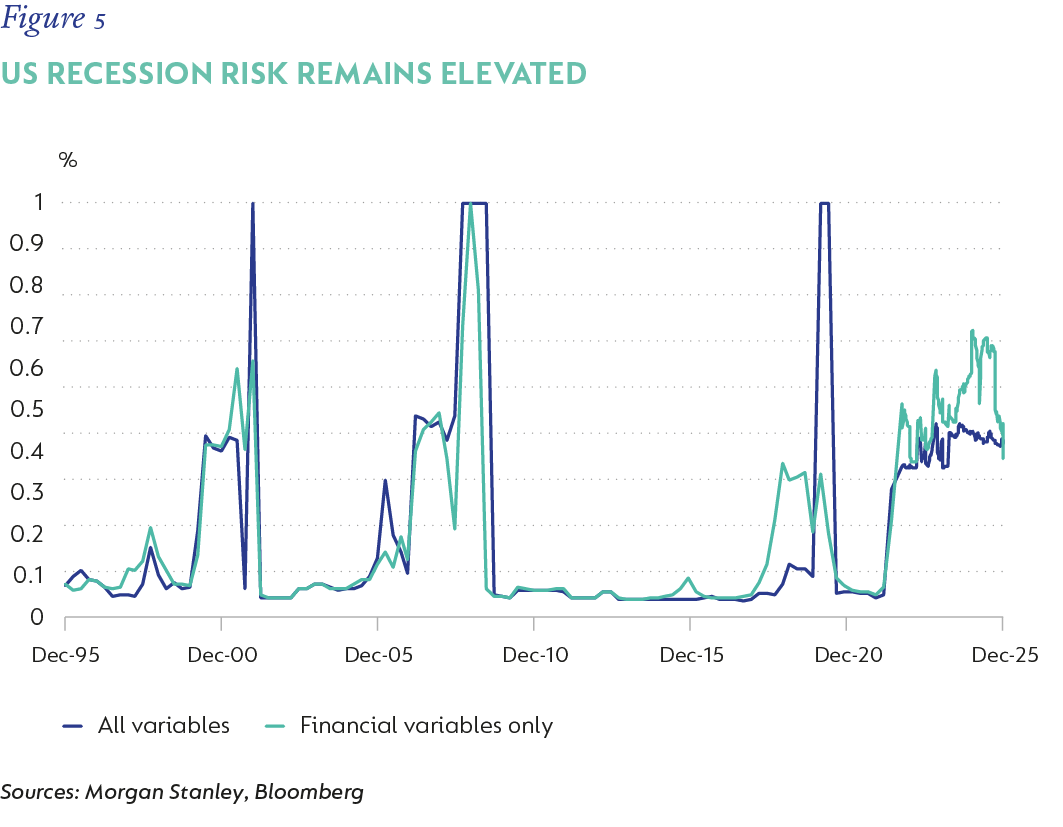

Despite expectations of some realignment of global growth dynamics led by the US, there is still a not-insignificant risk of a US recession (Figure 5). This reflects the fragility created by weakening labour markets and increasing income pressure as and when tariff pressure builds.

Key downside risks include:

- Faster-than-expected tariff pass-through to the consumer

- A sharper-than-expected labour market correction

- A financial shock, such as elevated equity valuations or mounting weakness in the US housing market

- Political interference in monetary policy (Fed interference, interest rate pressure)

AI has been the dominant investment theme of the cycle, but its macro impact remains highly concentrated. That is, a small number of firms globally account for most of the spending. It is possible that AI spending will boost domestic demand, notably in the US, more than productivity in 2026, with limited near-term spillovers. That said, productivity gains from AI will take time. History suggests that general-purpose technologies require sustained, broad-based investment before lifting aggregate productivity. For now, the gains are firm-specific, not economy-wide.

This tempers the “AI boom” growth narrative. It supports earnings growth in technology and related sectors, but does not yet justify a step-change in potential growth.

Upside risks appear narrower

Upside scenarios hinge on US consumer spending smoothing through ongoing margin absorption, savings drawdowns, and credit utilisation, alongside faster productivity gains, stronger fiscal spillovers, or a rapid improvement in business confidence. These are plausible but seem less likely in the near term.

Political uncertainty can have an outsized impact on confidence. The year has started with an unexpectedly decisive US action against Venezuela’s president, the broader regional and global implications of which will take time to evolve. Without doubt, this intensifies uncertainty about the evolving role the US will play in geopolitics.

2026 could prove to be a tipping point for Europe, which faces a confluence of pressures: ongoing external pressure from Russia, China, and the US, while internally weak, with a challenged and deeply divided leadership. The UK is at risk of another change in leadership (think five Prime Ministers since 2016), with a heavy schedule of local elections set to provide some indication of shifting sentiment.

While there is a fragile hiatus in the Middle Eastern conflict, this does not represent any permanent peace, and emerging markets are finding alternatives to traditional Western trading partners. This implies ongoing heightened political uncertainty, locally and externally, and uncertainty is the enemy of growth.

South Africa: Starting on a firmer footing, economic prospects improving

After a very uncertain start, South Africa ended 2025 on a much firmer economic footing than it began.

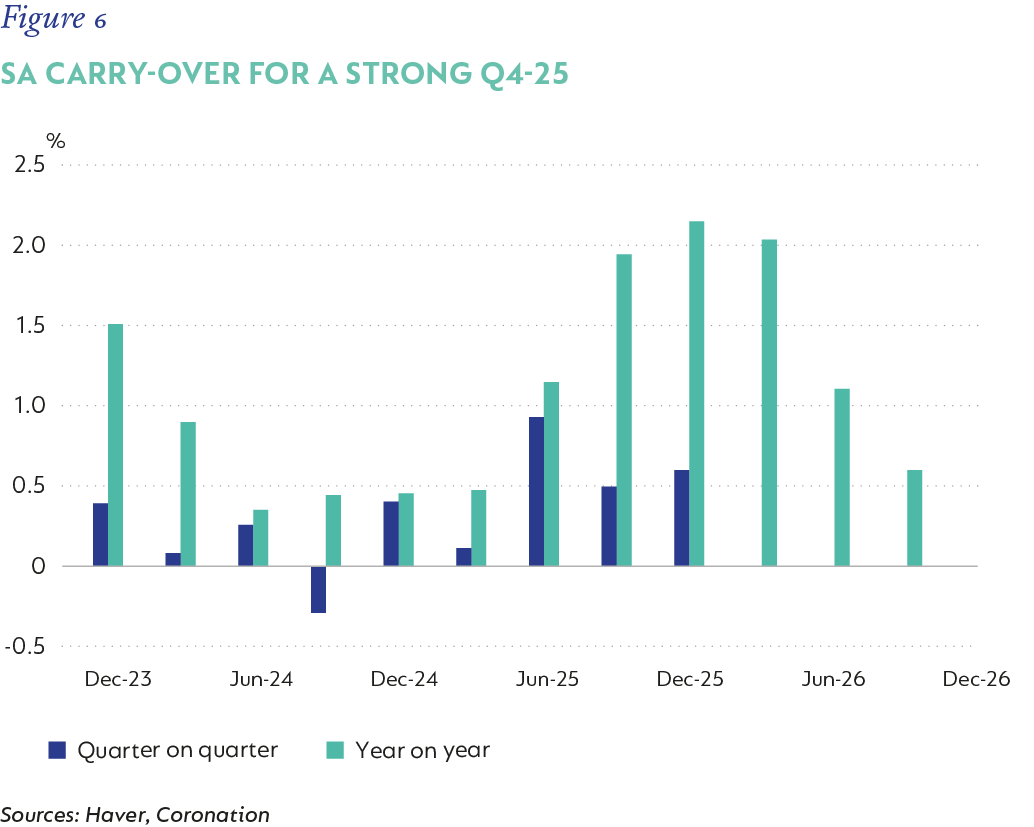

We expect growth of 1.6% in 2026. GDP growth looks set to surprise consensus to the upside, despite the weak start to the year. Undermined by global and domestic uncertainty, GDP growth was 0.1% quarter on quarter (q/q) in the first quarter of 2025, following a disappointing fourth quarter in 2024 (Q4-24) at 0.4% q/q. A decent upside surprise in the second quarter of 2025, with real GDP growth of 0.9% q/q and 1.1% year on year (y/y), followed by 0.6% q/q and 2.1% y/y in the third quarter (Figure 6).

Tracking data suggests momentum was sustained in Q4-25, with the full year likely to see real growth of 1.4%. Importantly, a strong finish bodes well for 2026 – with a statistical spillover of 0.9% in our base case. We are encouraged by an improvement in important forward-looking confidence indicators in key sectors in late 2025. Notably, the Bureau for Economic Research showed a marked improvement in construction sector confidence in Q4-25 to an 11-year high, supported by significantly improved activity and profitability. Business and consumer confidence also improved into year end.

Inflation undershot expectations for most of 2025. A combination of weak domestic demand, the rally in the currency, low oil prices, modest food inflation, and, more recently, outright deflation in some core goods prices helped lower consumer inflation from an average of 4.4% in 2024 to an estimated 3.2% in 2025. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) used this ‘opportunistic disinflation’ to lower its preferred inflation target to 3%, with the formal change finalised by the Minister of Finance at the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement in November.

Prospects for inflation to remain low in the year ahead are good: the rand has performed strongly and remains underpinned by favourable terms of trade, while global oil prices have moderated. Together, this allows for two large fuel price reductions early in the year. Low food prices look well supported by the large maize crop and good summer rains, and imported core goods prices should continue to benefit from a combination of ample global supply and a resilient currency.

Food and fuel are critical drivers of headline inflation. Keeping inflation low depends on containing rental and other services inflation, with the risk that, as the economy recovers, it generates renewed pressure on housing costs. We see a modest recovery in rental inflation, with upside risk in 2027. Administered prices that sit well above the 3% target remain a challenge, and wage settlements have yet to reflect the SARB’s new objective.

In this context, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) eased the policy rate by 75bps over three meetings in 2025, and should be able to cut at least another 50bps in 2026. A moderation in inflation expectations into end-2025 should contain the MPC’s perceptions of upside risk to its baseline.

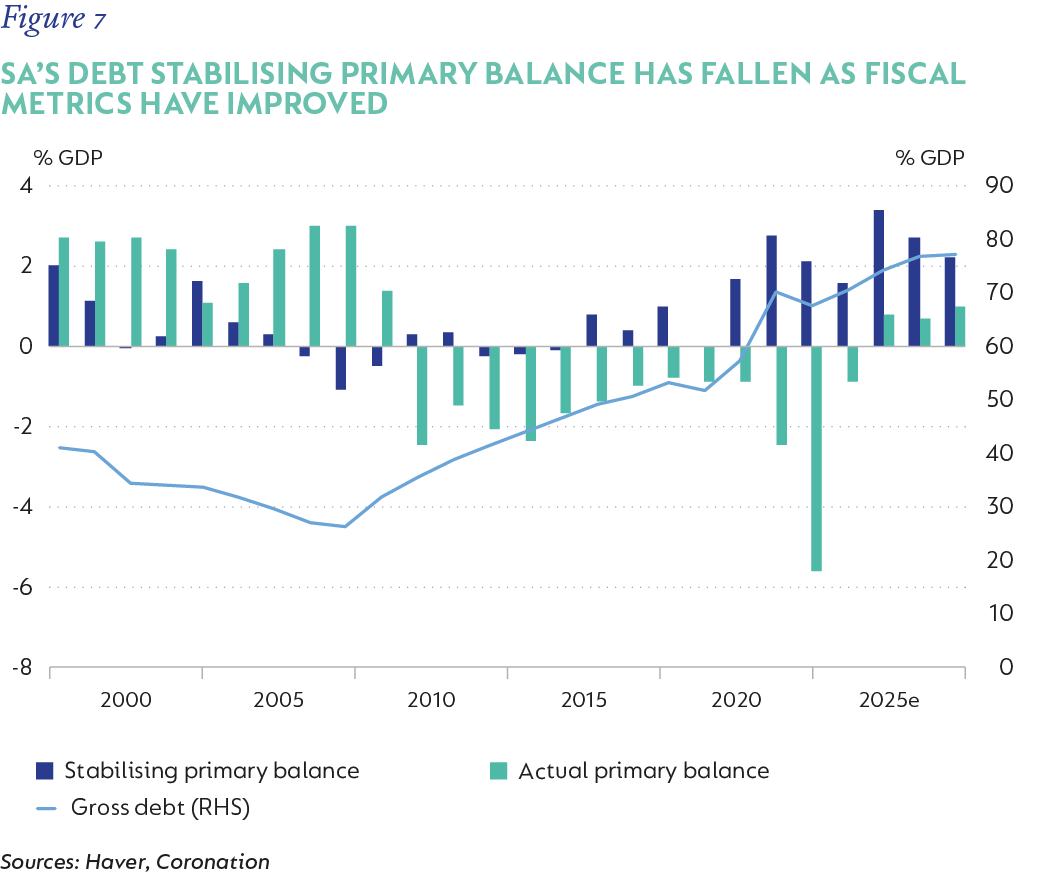

National Treasury fought hard to fulfil its commitment to a rising primary surplus and the stabilisation of debt to GDP in the current fiscal year (Figure 7). Two Budget false starts, derailed by the need to engage in a more consultative process than was the practice before the advent of coalition politics, resulted in a delayed start to the fiscal year.

To date, revenues have been well supported by VAT, personal income tax, and, more recently, evidence of a recovery in corporate profits, while spending has caught up in the later months of the year. We expect the final deficit to marginally undershoot National Treasury’s in-year forecast, at -4.3% of GDP.

Looking ahead, fiscal dynamics should benefit from the ongoing commitment to primary surpluses, as well as from the impact of lower inflation on indexed expenditure and borrowing costs. However, demands on the expenditure envelope remain considerable: the wage bill is still large and somewhat unpredictable; State-owned enterprises and municipalities require considerable reform; and shifting political dynamics cannot be eliminated as risks to the fiscus, where the position is still vulnerable.

Domestic politics was noisy in 2025, and the noise is likely to get louder in the build-up to the 2026 local elections and key party elections over the next two years. Noisy politics is a risk to the fragile recovery in confidence and growth.

CONCLUSION: A YEAR OF TRANSITION, NOT TRANSFORMATION

2026 is shaping up as a bridging year – between post-pandemic normalisation and a more balanced, synchronised paradigm. Growth is likely to remain positive, but at a pace determined by the balance of inflation persistence, fiscal limits, monetary support, and labour market adjustments.

The global economy is not heading for collapse. But neither is it returning to the pre-Covid playbook. Recoupling is coming – but it will be uneven, contested, and politically charged.

For investors and policymakers alike, the message is clear: resilience should not be mistaken for robustness.

[1] Fiscal impulse references whether government policy is supportive or restrictive of growth over time

Global (excl USA) - Institutional

Global (excl USA) - Institutional