Economic views

The eye of the storm

“The president can't change the country on his own. But what can he do? He can give an example.” - Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelenskyy; President of Ukraine

The Quick Take

- The watery post-pandemic dawn was short lived, and now storm clouds mar the horizon

- War in Ukraine will have complicated and long-lasting economic and geopolitical repercussions

- The complex nature of surging inflation makes effective policy setting difficult

- SA is benefiting from the export boom, but the real challenge remains stronger, reform-led long-term growth

THIS YEAR STARTED on a positive note. Two years after locking down, most developed economies had recovered their pre-pandemic levels of output. Despite the emergence of Omicron, disruptions to work, living and travel were generally less than during previous Covid-19 variants, policy responses less rigid and output less affected. In the US and Europe, household consumption was well-supported by high savings and tight labour markets and to varying degrees ongoing policy support. Growth was recovering well, and economic forecasts for the year ahead remained robust – if off the post-pandemic bounce of 2021. Monetary policy settings – although on notice for tightening – remained accommodative.

The outlook was not without challenges:

- global supply constraints remained tight, and, with them, amid loose policy settings and very strong demand, inflation continued to surprise on the upside;

- belatedly, the world’s major central banks had started to acknowledge that inflation is likely to be an enduring challenge;

- emerging markets in general have found it harder to return to pre-pandemic norms, with elevated levels of unemployment and indebtedness looking set to persist; and

- growth in China was visibly slower, with the outlook complicated by regulatory tightening and a zero-tolerance Covid policy.

These remain.

The February invasion of Ukraine by Russia has materially rearranged these challenges and is forcing us to reimagine the years ahead.

While the path to any kind of conflict resolution is hidden at this stage, several clear positions are emerging:

- A near-term negotiated ceasefire is unlikely, raising the risk of a long-drawn-out stalemate.

- Russia’s integration into the global economy has ended – some economic relations may persist, but these will be limited, and sanctions will probably continue well into the future.

- Global political dynamics have shifted meaningfully and abruptly – cementing a much closer alliance between the ‘West’, NATO, Europe and the UK, and a repositioning of opposition countries.

- Given Russia and the Ukraine’s contribution to global commodities trade, one of the consequences will also be that the shape and timing of energy reform globally has now changed, and commodities are likely to remain expensive.

INFLATION, BUT WITH GROWTH BUFFERS – FOR NOW

The most immediate economic shock is the impact on already-constrained global supply via sharply higher commodity prices. Combined, Russia and Ukraine’s contributions to global trade is relatively small, but they are important exporters of critical commodities, and not just oil and gas, but agricultural commodities, fertilisers and some industrial metals. According to the International Grains Council, Russia is the world’s largest wheat exporter, while Ukraine is the fourth largest, and the third largest corn exporter. Russia also supplies palladium and high-grade nickel. This is being exacerbated by China’s rolling Covid lockdowns, which are intensifying bottlenecks and shortages.

The broader economic repercussions are likely to be unevenly distributed across economies, although where prices are set globally (commodities), inflationary pressure will be impossible to avoid. The US, for example, is relatively closed and more flexible in its supply and demand for goods and services, growth dynamics are positive, and the labour market is tight.

Europe, by contrast, is geographically closer to and more integrated with both Russia and Eastern Europe where there is greater risk of spillover, and its reliance on Russian energy is a significant vulnerability. But, here too, there are considerable buffers in place, with low unemployment, high levels of savings and sufficient fiscal resources to provide a fillip. So, in general, revisions to forecasts to date have been bigger for inflation than those to growth expectations and are concentrated in 2022.

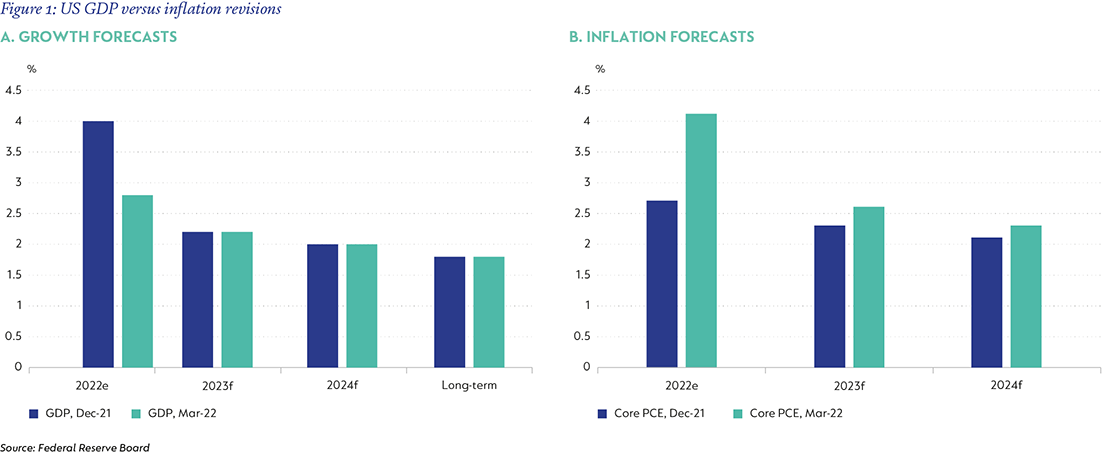

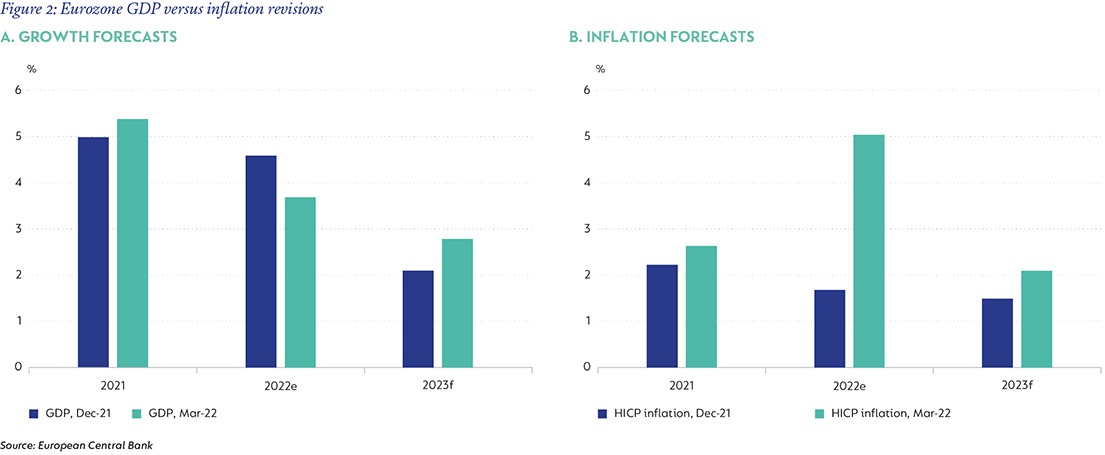

In March, the US Federal Reserve Board (the Fed) revised its core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation forecast to 4.1% for 2022 (from 2.7% in December and 2.6% for 2023 (Figure 1a)). Growth is expected to slow as a result of lower real incomes and weaker consumption, but the 2.8% real GDP forecast for 2022 is still relatively robust and is expected to hold above 2% in 2023 as labour markets remain resilient (Figure 1b). In this context, upside risk to inflation is likely to see the Fed accelerate its rate hikes to include 50 basis points (bps) increments.

In Europe, with its much closer proximity to the conflict and greater exposure to the sharply higher gas prices, inflation is set to accelerate more strongly and growth to slow more sharply. Current forecasts imply growth below 3%, markedly down from expectations of over 4% at the start of the year and about 2.2% in 2023 (Figure 2a). Inflation (as measured by the Harmonised Consumer Price Index [HCPI]) is expected to peak above 8%, as the spike in gas prices is embedded in the numbers, with risks to the upside as supply disruptions could adversely impact a wider range of goods and services (Figure 2b). Despite the elevated risks, the European Central Bank (ECB) continues to signal only gradual policy normalisation, with the first rate hike expected by the end of the year, and 25bp incremental tightening through 2023 being the most likely scenario at this stage.

While growth buffers in both regions are expected to provide some offset for inflation-related real income erosion, a combination of sustained inflation and higher policy rates is a growing threat to this delicate balance.

WINNERS AND LOSERS

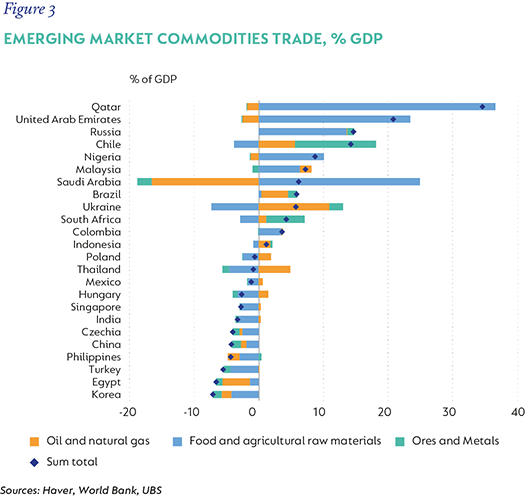

Previous commodity shocks have also created relative winners and losers, depending on the impact of relative prices on their terms of trade. Through this lens, Asia is the biggest net commodity importer and is therefore more vulnerable to higher prices, while Latin America, and MENA are the biggest net exporters. By commodity type, oil and gas typically form the largest share of trade, with the big net exporters, unsurprisingly, being Russia, Chile, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia. On the other end of the spectrum, the most significant emerging market net importers of fuel are Turkey, Egypt, the Philippines and India (Figure 3). These economies are most likely to suffer large, and perhaps constraining, balance of payment challenges, should oil prices remain elevated without offsetting financing flows.

In the ‘middle’ there are a handful of emerging market countries with more diverse export baskets, including those exporting agricultural produce. Concentrated in Latin America, these include Brazil, Mexico and Colombia as well as South Africa (SA). Here the benefit from the current rise in prices may be concentrated in gains to the current account but should reverberate to benefit these economies more broadly if sustained.

SOUTH AFRICA, A ‘WINNER’?

SA is almost uniquely placed here. With deep, liquid and investable markets, SA’s export basket comprises both agricultural commodities, and metals and ores, as well as coal, where prices have risen significantly, enough to offset the rise in the price of oil, which SA imports.

The avenues through which the economy benefits from this tailwind run primarily through export earnings and government revenues. Unfortunately, the ‘sails’ the domestic economy has to catch these positive tailwinds in order to amplify their economic impact have diminished through time, as there is no longer adequate infrastructure to do so. Specifically, the compromised electricity sector limits the expansion of production in response to higher prices; rail and road transport inefficiencies also limit companies’ ability to increase production and realise higher export prices. Nonetheless, the extended rise in terms of trade should prolong the economic recovery that gained traction in 2021, not just through trade and revenue, but also through support for income and consumption.

The SA economy grew 4.8% in 2021, after contracting 6.4% in the 2020 Covid year. Last year’s recovery was badly interrupted by the Gauteng/KwaZulu-Natal unrest which erupted in the third quarter, materially exacerbating the weak employment situation and stalling growth momentum that was already impacted by shutdowns related to the Covid Delta variant. Activity recovered in the fourth quarter, with the economy growing 1.2% quarter on quarter across a broad base, supported by household spending and exports which were the strongest contributors to the recovery.

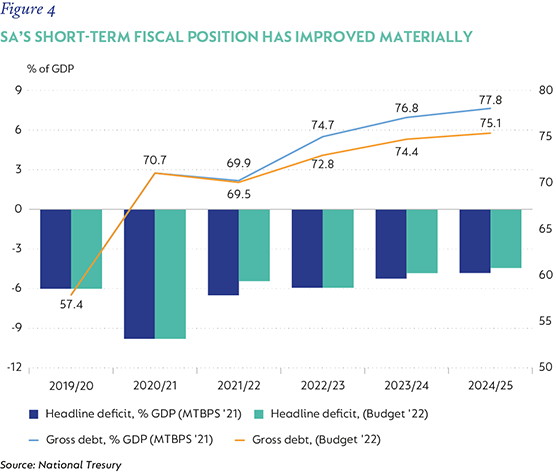

Importantly, the fiscal position benefited materially from these growth dynamics. Against expectations as late as the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) in October 2021, the revenue over-run announced in February 2022 was R65 billion, and the deficit for the 2021/2022 fiscal year is expected to shrink from -9.9% of GDP in 2020/21 to -5.8%, almost a percentage point less than the October estimate of -6.6% (Figure 4). In line with this, government’s debt stock – although much higher than before the pandemic – should moderate slightly. Again, this is an outcome that is much better than earlier expectations, putting government finances on a somewhat less fragile footing.

We expect growth to top 2% in 2022, with upside risk to this estimate. Activity data for the first quarter of 2022 is strong, and the reopening of the economy paves the way for a broader-based recovery later in the year. There is also room for progress in realising reforms to contribute positively to growth, notably the eventual auction of high frequency spectrum, the opening Bid Window 6 of the Renewable Energy independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPP) in April, and renewed efforts by Operation Vulindlela in the Presidency and the private sector to overcome red tape hindering companies’ ability to invest in up to 100 megawatts of private power generation. The weak labour market remains a significant drag, despite the return to normal of aggregate compensation, although, here too, there is potential for some improvement. Rising inflation and policy rates, however, are a gathering headwind.

SA’s inflation outcomes have, until recently, been more benign than seen elsewhere. The resilient currency (helped by the strong external position) limited the rise in imported inflation, while low domestic pricing power coupled with low food and services inflation, have provided a strong anchor for both headline and core measures. However, higher commodity prices imply a less positive story going forward. Fuel prices reached 29.4% year on year in February, and are set to accelerate further into mid-year off a weak base. While some moderation may come thereafter, we expect global oil prices to remain relatively elevated, limiting the disinflationary base.

Food inflation is a growing concern. SA is a net exporter of agricultural commodities, but a net importer of wheat and agricultural inputs like fertiliser. Domestic supply dynamics are still positive, and this helps limit price pressure, but if grain prices remain high for an extended period, livestock farmers may opt to cull herds and flocks, which could ultimately push meat inflation up too, extending the time that food inflation remains high. We have revised our food inflation forecast up to reflect these dynamics, but still see some risk of prices being higher than our elevated expectation.

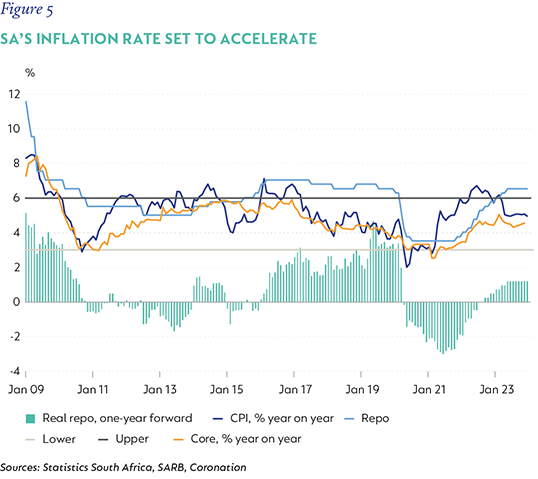

The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) started normalising the repo rate from its accommodative position in late 2021. To date, 75bps in rate hikes have been implemented and the repo rate is 4.75%. The meaningful deterioration in global inflation outlook of the past six to 12 months, coupled with rising domestic pressures, is likely to see the Monetary Policy Committee continue a steady pace of rate hikes, with the risk that tightening is accelerated in the near-term in line with less favourable outcomes and deteriorating inflation expectations (Figure 5). While we don’t see either the rise in inflation and its impact on real incomes or the baseline tightening in monetary policy as likely to have a significant impact on growth in the near term, the clear risk is that these combine to a much tighter policy environment domestically, at the same time that global growth comes under increased pressure.

THE REIMAGINING

This baseline implies a relatively benign glidepath, given the dark clouds we can see. But the shape of challenges outlined above will inevitably change. Most immediately, inflation may be high for much longer than current forecasts anticipate. Should policymakers be forced to respond aggressively, growth will slow. Countries that run large deficits could become dangerously constrained as funding costs rise. High levels of debt increase fragility, and emerging markets in particular are vulnerable.

In SA, the biggest challenge remains stronger growth. We have been lucky that terms of trade windfalls have shored up fiscal and external vulnerabilities, but these will fade, and our ‘reimagining’ may well be a return to low growth, higher inflation and an unsustainable fiscal position. In the eye of the storm, the urgency of enabling reform is even greater than before.

Disclaimer

SA retail readers

SA institutional readers

Global (ex-US) readers

US readers

Global (excl USA) - Institutional

Global (excl USA) - Institutional