Investment views

Not another scary movie

What just happened?

The Quick Take

- In spite of a quick succession of US bank failures, we don’t believe it poses a global systemic risk

- Inadequate banking sector regulation of US banks outside the top 10 nullified post-GFC checks and balances

- The low interest/low inflation environment of the 2010s and 2020s saw US banks running significant interest rate mismatches in their asset:liability mix resulting in a blowout when the Fed aggressively hiked rates

- This is a US bank issue, and we think that it has resulted in a buying opportunity of banks elsewhere rather than a crisis

In March, the world was once again shaken by a significant bank failure in the US. Despite the fallout from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008/2009 still being fresh in people’s memory and a whole host of new bank regulations having been implemented since then, the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and, shortly afterwards, Signature Bank, roiled financial markets around the world. Then, by the weekend after SVB was put into curatorship, Credit Suisse, the 167-year-old Swiss banking giant, was hastily shoehorned into a shotgun wedding with UBS. This quick succession of concerning failures saw investors and regulators around the world asking whether this was the start of another banking crisis*. Equity markets, and especially bank share prices, came under immense selling pressure as a result. That leaves investors with the question: is this the beginning of another 2008 style global banking crisis? We would argue not.

THE START

The basic principle of banking is to borrow money from depositors and on-lend it to clients, thereby earning a spread, in other words the difference between the deposit rate and the lending rate. There is, however, also a timing issue. Borrowers typically want the money for a fixed time period matching the period of the asset they are buying. Short term for a consumer loan, medium term for a car loan and long term for a property loan. On the other hand, depositors generally always like to be able to access their money whenever they want to.

Banks have operated in this maturity mismatch environment since the inception of banking. This was an area of focus after the GFC and various new metrics and measures were introduced to reduce the risk of bank runs where depositors demand their deposits and the banks are unable to meet these demands because they have invested in illiquid, long-dated, opaque loans. At that time, the key rule proposed and adopted by the Basel III banking community was the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR), where a deposit-taking institution rates the quality of its deposits from good (small, individual deposits) to risky (large, concentrated deposits from sophisticated financial organisations), based on the principle of how ‘sticky’ these deposits would be in a crisis.

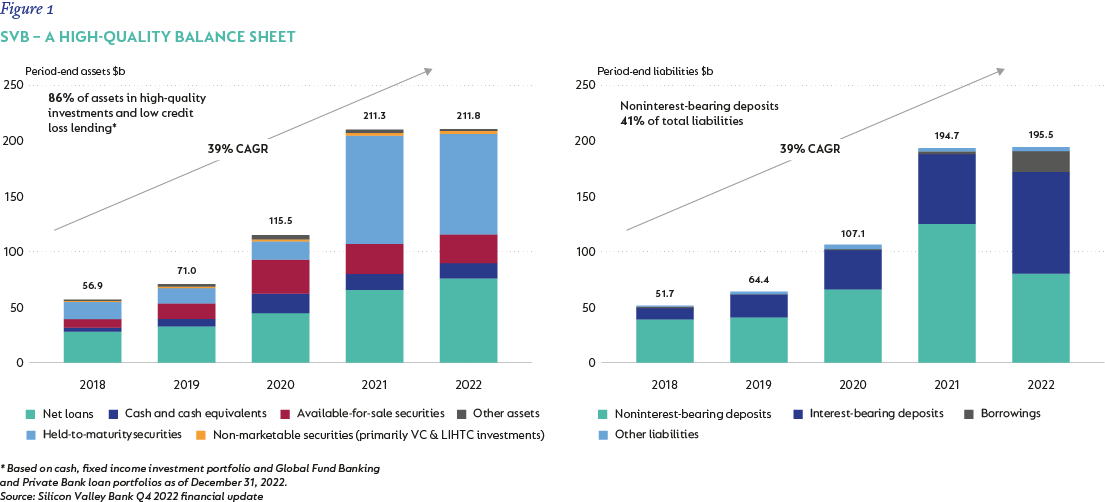

The US, however, given aggressive lobbying, decided not to implement this rule in line with the rest of the world. They finally, in 2021, implemented a form of the NSFR, but once again due to lobbying, only applied it to the top nine banks in the market. SVB was the 16th largest bank in the US with a balance sheet of roughly $200 billion (R3.6 trillion!) – see Figure 1.

On the other side of the deposit funding is what kind of assets and loans the bank invests in. As the GFC was driven by complex derivatives based on poor-quality collateral, one of the key outcomes of the 2008 crisis was to grade the quality of assets that banks invest in. Simply put, poor-quality and illiquid assets would require more stable funding, but high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) would require significantly less funding, because the theory was these assets would be easily realisable and would not incur a loss on realisation. There was therefore every incentive for banks to invest more of their assets into HQLA, and the most easily available and highest quality HQLA was sovereign bonds – aka: debt issued by your own government. And what government could be safer than the US government, the owner of the world’s reserve currency, the US dollar? Figure 1 above from SVB’s most recent presentation proudly talks to a quality balance sheet!

THE MIDDLE

Most of the preceding decade (the 2010s) was marked by exceptionally low interest rate levels. Many countries recovering from the GFC kept interest rates artificially low to allow governments to fund the various recovery plans. During this period inflation was well behaved, allowing these interest rates to be maintained at very low levels. Then Covid struck and interest rates were pushed even lower, going negative in many European countries and very close to zero in most others. In this environment, all investors were incentivised to take on more risk in order to eke out a slightly better return than zero.

One of the ways to get a yield pickup was to take on more duration risk. Essentially this means to lend to someone for a longer period, as you could typically earn a higher margin for doing this. One of the easiest and supposedly lowest risk ways of doing this in the US was to lend more money to the government. The longer the loan period, the higher the interest rate. And, because the loan was considered a HQLA, you didn’t have to hold a lot of capital or as much short-term liquidity against these loans, thus allowing for more gearing. Some amount of this kind of lending is acceptable, but SVB really pushed the boat out, and no one was watching them.

The bank went through a period of spectacular growth during Covid, with its deposit base expanding from $62 billion in the first quarter of 2020 to $198 billion by the first quarter of 2022 – that’s an increase of 219%. This spectacular growth being driven by its position as banker to Silicon Valley startups, all of which attracted huge amounts of capital during the Covid years. Without any real demand for loans, they invested more and more of the deposits into government and government guaranteed debt, which went from $27 billion to $127 billion (that’s 370%) over the same two-year period. A number of other smaller and mid-size banks did the same, but nowhere near to the same extent, but, because the regulator wasn’t focusing on them, they could get away with a major maturity mismatch.

THE END

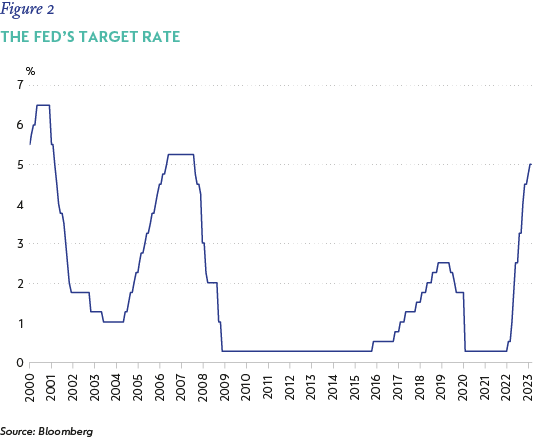

Nominal government bonds have a fixed interest rate, and in the US, even their homeloans are all fixed-rate loans as opposed to most other markets where loans are floating-rate loans or very short-dated fixed-rate loans. What this means is as much as you are not taking credit risk when lending to the US government, you are taking interest rate risk. This is the risk that you lock in a low interest rate on your loan, and are then exposed to rising interest rates paid to depositors in the interim. As discussed, during the Covid period interest rates went to zero or negative in the short term and the yield on US 10-year bonds went as low as 50 basis points (bps) during the peak of the Covid crisis. This means that if you bought a government bond at that time, you locked in a return of 50bps for 10 years. Since March 2022, the Federal Reserve Board (the Fed), being very concerned about spiralling inflation, has hiked overnight interest rates from 0.25% up to 5% increasing the price of short-term money from 0% to close to 5% (Figure 2). If you locked in a return of 50bps and are now facing a funding cost of 500bps, you are in trouble.

Recognising that in an environment of much higher interest rates a yield of 50bps is unattractive, the prices of government bonds were falling as short-term interest rates were rising, reflecting the difference in return that you could earn. It didn’t mean you weren’t going to get paid back the full loan amount at the end of the term (credit risk), but it reflected the fact that you were losing out on the time value of money (interest rate risk). Because banks are impacted by sentiment, one of the key accounting fundamentals is that loans that are being held till maturity do not have to be marked to market. This prevents short-term moves in interest rates from causing volatility in their income statement and worrying investors. However, given the size of the portfolio of government bonds on the balance sheet of SVB, it was easy for depositors to work out that if they did mark to market the value of their government bond portfolio then the entirety of the bank’s capital would be wiped out. This startled its concentrated base of Silicon Valley startups and venture capitalists who started withdrawing their deposits as fast as a mouse click would let them. This transformed ‘unrealised losses’ on a held to maturity portfolio into ‘realised losses’ as SVB was forced to sell this HQLA to meet the outflows.

As they recognised more and more losses, the spiral of outflows picked up and the bank was put into receivership on 10 March 2023. But fear was spreading, and depositors and speculators had already moved onto the next target, Signature Bank in New York, which had none of the same exposures as SVB, but did have a crypto platform that had been losing deposits. As depositors withdrew cash, the Fed stepped in and placed Signature in curatorship. At the same time it guaranteed all bank deposits held by the two failed banks in order to allay depositor fears, and also provided unlimited liquidity lines to all US banks in order to try prevent depositors from panicking and pulling their funds. This ultimately slowed and stopped the crystallisation of losses for those banks that had similar bond portfolios and also reduced the pressure on liquidity in the US banking system. Shortly afterwards the assets and liabilities of SVB and Signature have been bought by other banks.

REPERCUSSIONS

Just a week after the SVB and Signature meltdowns, regulators approved a UBS buyout of Credit Suisse at a fraction of its net asset value and with a painful $17 billion wipeout of its tier one debt. This is despite the fact that its balance sheet did not face any of the asset liability mismatch that affected SVB. The problem that Credit Suisse faced is that in a banking crisis, depositors and speculators always look for the next weakest bank, and as it had been suffering through years of mismanagement as well as bad lending and risk controls, the Swiss banking icon was an obvious candidate.

The final nail in its coffin was when during what seemed a fairly benign Bloomberg interview with the Chairman of Saudi National Bank he was asked if he would put more capital into Credit Suisse, and his answer was an emphatic ‘No’ (because of regulatory issues that would see their stake cross important reporting thresholds). This was taken by the market as a vote of no confidence, and the bank immediately saw a similar run on deposits starting, forcing the Swiss National Bank to effectively push through the UBS merger over the weekend of 19 March. After some further aftershocks and volatility, markets have settled down as investors and depositors recognised this was not a repeat of the GFC, but instead a very localised US banking issue.

Share prices of banks, however, have all come under pressure during this period, and have not recovered all the losses incurred since the panic started. SA banks, which are completely delinked from any of these concerns, all came under selling pressure, despite all of them reporting outstanding results during this same volatile period. Perversely enough, the driver of the strong SA bank earnings in this period, and expected for the year ahead, is exactly the same factor that resulted in US banks incurring losses, that is: rising interest rates. SA’s big banks are tightly regulated and run very professional asset liability committees, which ensure that they do not get caught out by significant shifts in interest rates. For the most part, the banks use the rise or fall in interest rates as a natural hedge against their credit losses. We remain very comfortable with our SA banking position and have in fact added through this period. Despite the issue with Credit Suisse, this remains a particularly American-only banking crisis. America has over 4 400 separate banks, the majority of which have been operating outside of the intense regulatory scrutiny that the top 10 US banks, and most other regions’ banks, operate under. Since the Fed made available liquidity facilities, we have seen the crisis abate, and, for the last two weeks, US banks have actually been paying back some of this excess liquidity. Outside of the US, this has been a great opportunity to buy banks given the unique US-specific centricity of this crisis.

* Since publishing, US regulators took control of First Republic Bank on 1 May 2023 and sold its assets to JP Morgan Chase, guaranteeing depositors access to their money. We believe that swift action by regulators and the banking sector has prevented contagion

Disclaimer

SA retail readers

SA institutional readers

Global (ex-US) readers

US readers

Global (excl USA) - Institutional

Global (excl USA) - Institutional