Economic views

A pause to re-evaluate

- “the united states has become the largest source of geopolitical uncertainty in the world. it's an extraordinary development.” - Ian Bremmer on X

The Quick Take

-

Global growth risks rising: H2-25 will be defined by whether weakening data due to tariffs and policy uncertainty are offset by resilient demand. US growth is set to slow, inflation remains sticky, and monetary easing is uneven across regions.

South Africa: political strain, weak growth: the GNU has struggled to deliver reform. Structural constraints and policy uncertainty have stalled investment and are likely to keep growth below 1% in 2025, with only modest improvements in 2026.

Policy Asymmetry: Europe's looser fiscal and monetary policy mix contrasts with US constraints as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act increases fiscal fragility.

In a presentation at the start of the year, I outlined Five Themes for Twenty-Five – a framework for interpreting the macroeconomic environment, identifying the risks likely to shape outcomes, and understanding how these might influence asset prices. These included the economic implications of a new round of protectionist US trade policy; the path of global government debt – notably in the US; the persistence of inflation in both developed and emerging markets; the market impact of elevated geopolitical risk; and whether 2025 might finally offer South Africa a structural growth inflection.[1]

By mid-year, some contours have become clearer. Global growth has proved more resilient than expected, despite the reintroduction of meaningful uncertainty. Inflation remains sticky – especially in the US – while Europe and emerging markets are seeing more consistent disinflation. Fiscal risks, particularly in the US, have intensified. Tariffs, geopolitical conflict, and fractured sentiment have all contributed to an unusually complex and asymmetric macro environment. These dynamics are unlikely to fade in the second half of the year.

TARIFFS: A LARGER SHOCK THAN EXPECTED

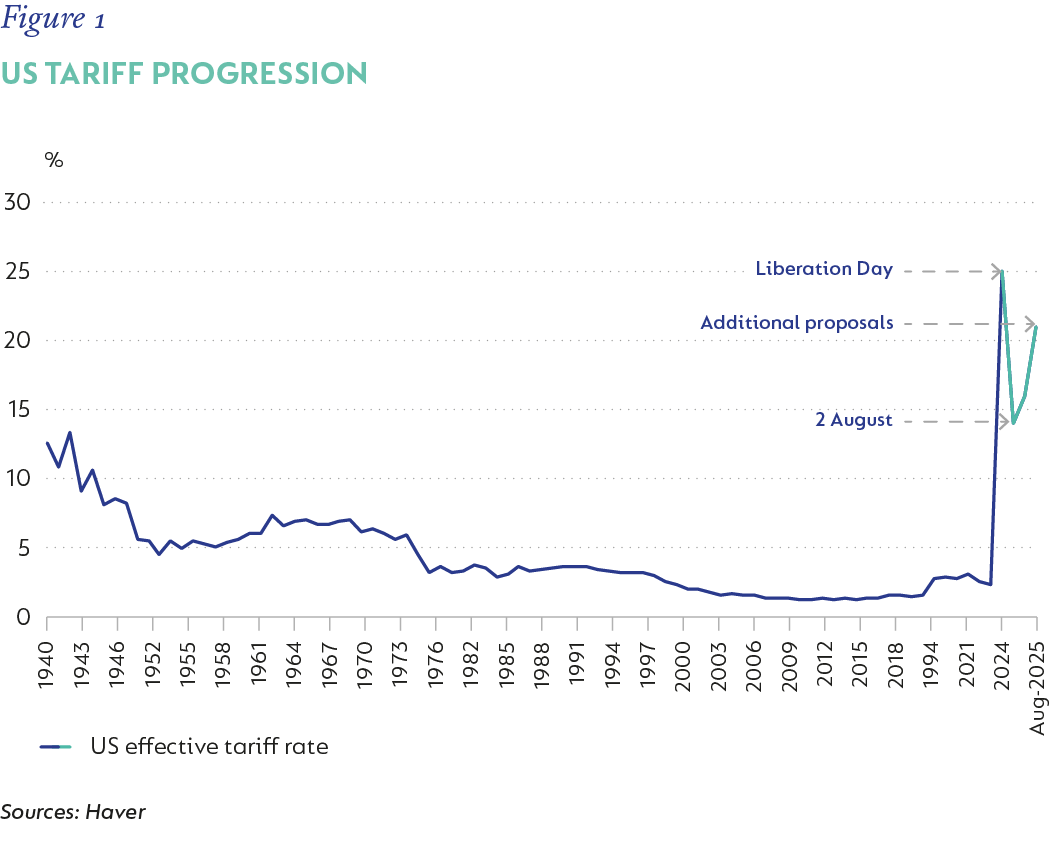

The most significant surprise of the first half of 2025 (H1-25) was the scale of the 2 April ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs. The average US import tariff jumped from 2% to over 25%, before moderating to 16% following a temporary pause. As the July deadline came and went, negotiations continue, as does the uncertainty surrounding what an end-tariff regime may look like. Should additional measures on Canada, Mexico, and Brazil materialise, that rate could move towards 21% (Figure 1).

Although investor focus has since waned somewhat – as some “tariff fatigue” has set in, policy risk remains front and centre. Under US trade laws, sections 301 and 232 provide the administration with legal cover for further escalation over the duration of the current US presidential term, though risks remain two-sided: a partial US-China agreement could trigger some rollback. Meanwhile, pending court decisions (businesses/various states vs government) as to the validity of President Trump invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act continue to cast uncertainty over existing measures.

In assessing the likely impact of these significant increases in import tax, the ability of corporates and consumers to absorb tariff shocks will be critical, particularly as signs of pass-through to inflation are starting to emerge. Available data suggests that there has not been a significant drop in goods export prices to the US – one way in which exporters could try to hold market share by absorbing the tariff. This implies that the shock will be taken on margin by US importers or passed to consumers.

Nevertheless, tariffs are contributing to a visible divergence in global data.

HARD VS SOFT DATA: THE GREAT DISCONNECT

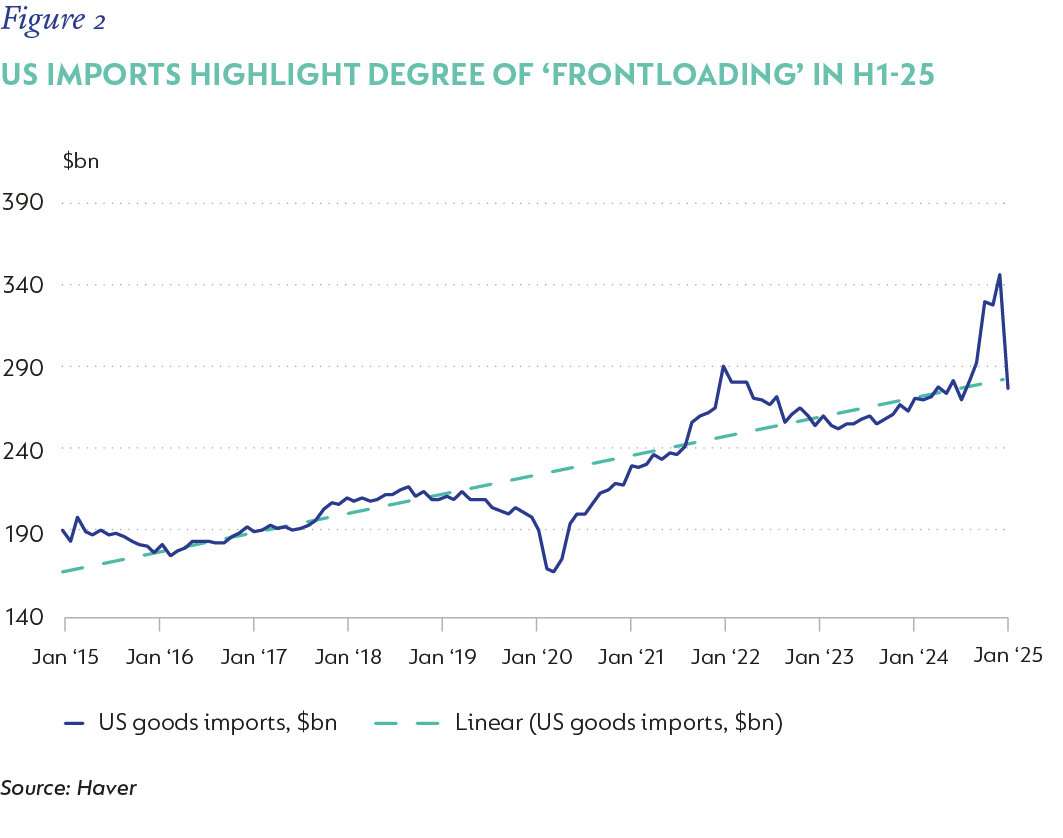

This divergence has emerged as a key theme: hard data, such as GDP, employment, and production, have held up reasonably well; while soft data, which include sentiment and survey-based indicators, has deteriorated. The gap between the two is now the widest in decades. UBS estimates that while hard data imply global growth of roughly 3.6% this year, including the impact of frontloading of trade, which was evident in the first quarter of 2025, soft survey data point to something closer to 1.3%. The frontloading of US imports (Figure 2) will likely unwind in the second half of the year (H2-25); however, forward-looking data does not yet clearly signal a slowing in goods manufacturing, which makes the timing of this unwind more difficult to estimate.

We expect a “tug of war” between weakening macro data resulting from the tariff shock and the underlying resilience of the US and global economies to be the theme of H2-25. As the impact of higher import prices puts pressure on the margins of importing companies in the US, both investment and labour markets should loosen. At the same time, rising consumer prices as a result of the tariff shock are likely to undermine real incomes, and thus consumer spending, which is the biggest driver of US growth. It is unclear, too, how the escalation of immigration policies in the US might undermine US growth momentum. We expect US growth to slow sequentially through H2-25, with the third and fourth quarters returning annualised growth at 1.0% and 0.5%, respectively. While a US recession is not currently our base case, the risk of a recession over eighteen months has certainly increased.

The euro area is projected to follow a similar pattern – bottoming in the second half of the year and rebounding into 2026. Here, the impact of the European fiscal stimulus is emerging as a significant tailwind. Global trend growth should re-emerge in 2026, which will become a more dominant narrative for asset pricing in the second half of the year.

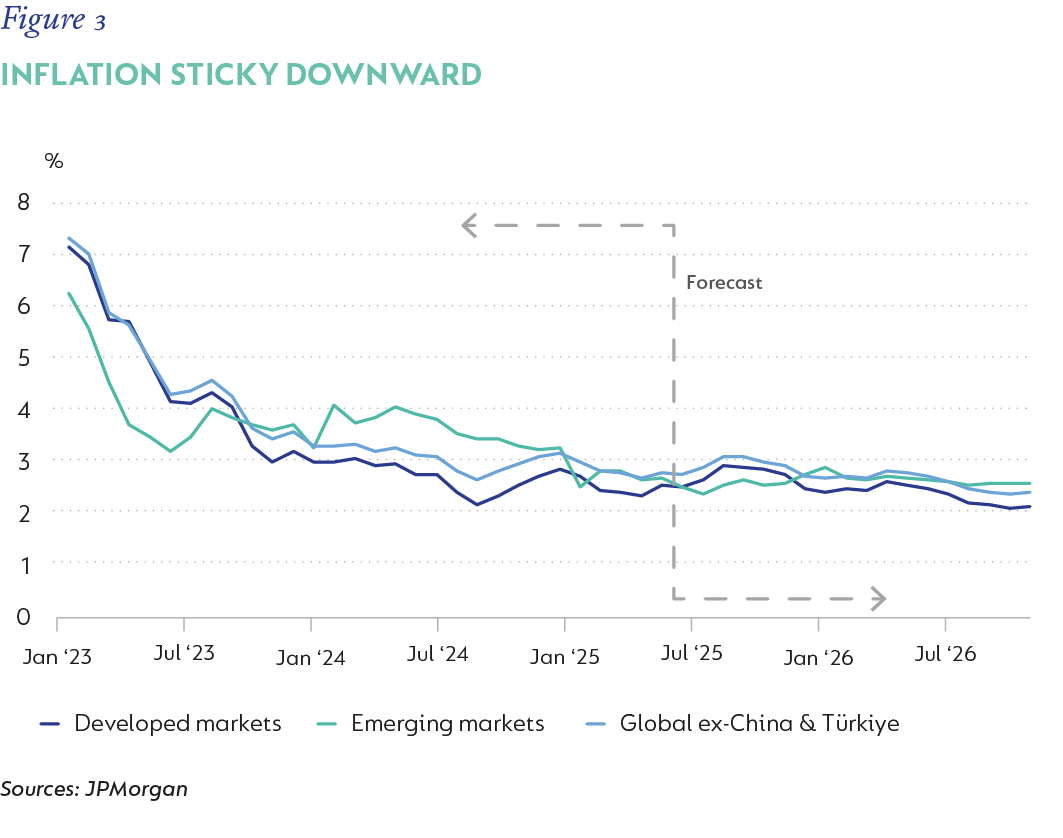

INFLATION: STICKY AND UNEVEN

Disinflation in developed markets has slowed. Developed market aggregate headline inflation fell just 0.3 percentage points between December and June (Figure 3), with much of the move driven by energy prices. Core inflation in the US remains stubborn – services inflation has decelerated modestly, but the June CPI print showed core goods inflation surprising to the upside, likely reflecting early tariff pass-through. In the near-term, US inflation is expected to reaccelerate, with core inflation moving towards 4% year on year (y/y) by the end of the year, before moderating towards target in late-2026. While the Federal Reserve Board (Fed) has held policy rates steady year-to-date, with resilient data and intensifying policy uncertainty, we expect weakening activity data to allow the Fed to ease in H2-25, with 50 basis points (bps) of cumulative rate cuts in the baseline, and room to move further in 2026. We expect the terminal Fed Funds rate to settle around 3.5%, which is above the Fed’s long-run estimate, consistent with a “higher for longer/incomplete cutting cycle” regime.

In contrast, inflation in Europe and the UK is expected to converge more consistently toward central bank targets. This should be aided by weak growth and a stronger disinflation impulse from currency appreciation. The European Central Bank’s policy easing path is further along, with 25bp cuts at each meeting through H1-25 and at least one more priced before year end, taking the deposit rate to 1.75%. The Bank of England has cut more cautiously, but further easing of the base rate by 25bps to 4.0% is likely by year-end.

ASYMMETRIC POLICY AND FISCAL REFLATION

Policy asymmetry has become more pronounced. Europe’s policy mix – looser fiscal policy and easing monetary conditions – stands in contrast to the more constrained US policy posture. The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) in July materially raises fiscal sustainability risk in the US and will see larger deficits and bigger issuance in coming years (starting immediately, given the lifting of the debt ceiling embedded in the Act). Forecasts produced by the Congressional Budget Office and the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget show US deficits in the range of 6.5% to 7% of GDP for at least the next decade under the OBBBA, and government debt rising from 98% currently to 127% by 2034 (from 117% forecast previously). Should the provisions in the Act not expire as currently written, this could be higher. The large cumulative deficits, coupled with high existing debt stock, make the US fiscally fragile and at risk of weaker growth outcomes. We expect borrowing costs to come under more pressure over time. While this is not an immediate threat to easier monetary policy, the large increase in issuance and a more vulnerable fiscal position do complicate monetary policy considerations over time.

In Europe, the ReArm Europe plan, a 4.5% of GDP defence and security initiative, combined with Germany’s domestic stimulus amounting to 21% of GDP over twelve years, marks the largest coordinated fiscal expansion in more than a decade. Growth is expected to benefit, with German real GDP seen lifting to 2% in late 2026, and an aggregate recovery in EU GDP growth to just below 2% over the same timeframe.

Within emerging markets, we expect growth to slow further in H2-25, with the biggest impact in Asia, where frontloading had the most positive impact in H1-25. Chinese growth is still very vulnerable, although a bottoming in real estate activity and further anticipated fiscal stimulus should provide a fillip. Emerging market GDP is seen slowing from just below 4% annualised in H1-25 to 2.5% annualised in H2-25. With limited fiscal space and inflation pressure, which is expected to keep moderating, emerging market central banks should be able to ease further in coming months.

GEOPOLITICS AND THE AI VARIABLE

In addition to economic uncertainty, there are two very visible non-macro forces shaping outcomes. First, geopolitical risk remains acute. In Ukraine, the front lines have largely stabilised, but the war remains attritional, with limited progress by either side. In the Middle East, Israel’s conflict in Gaza has entered a protracted phase, with no clear political resolution in sight. There are growing concerns of regional spillover, especially following renewed tensions along the Lebanese border and in Syria. For oil markets, the implications have been mixed: while geopolitical risk has contributed to a modest risk premium, supply disruptions have been minimal so far. Should either conflict escalate materially – particularly if Iranian production is affected – upward pressure on prices could re-emerge quickly.

Second, the artificial intelligence (AI) theme continues to broaden. Further productivity and efficiency gains are likely, but so is sectoral disruption.

SOUTH AFRICA POST-ELECTION: A FRAGILE COALITION AND STALLED GROWTH

The formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU) in mid-2024 prompted a spike in confidence, with surveys and markets anticipating that a more balanced political arrangement would mobilise greater policy and economic efficiency. While the outcome avoided a more volatile populist coalition, the resulting configuration has been politically combustible. Tensions have emerged between GNU partners over contested legislation, ideological differences, and unresolved local government dynamics – most notably in Gauteng. Although national structures have held, the absence of a unified policy front has weakened the GNU’s ability to execute on core economic reforms.

These political tensions peaked in H1-25 when the Democratic Alliance opposed the National Budget in February. This led to a protracted revision process and sequential delays in the tabling of the legislation and materially raised public uncertainty about the budgeting process and the ability of GNU member parties to continue to cooperate politically. The ultimate Budget dialled back on a proposed VAT hike in the original iteration but raised revenue through economically painful personal income tax adjustments, while raising spending on State employees. We expect National Treasury to hold firm on delivering primary surpluses, but in the absence of sustained, stronger growth and lower borrowing costs, we do not think a debt peak in the current year can be sustained over time. That said, we see room for the fiscal position to be better-than-expected in 2025/2026, given the delayed start to spending this year.

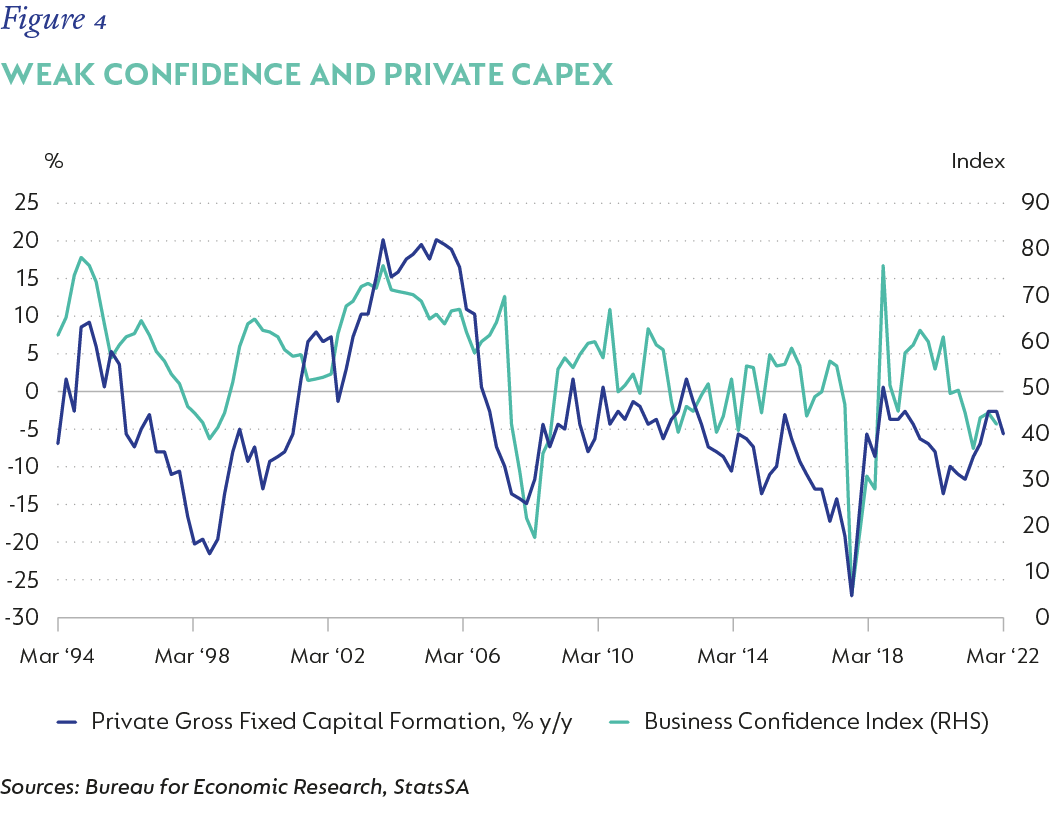

GDP growth was disappointingly weak in H1-25. After sequential growth of just 0.4% y/y in Q4-24, growth was 0.1% in Q1-25. Tracking data suggests an acceleration to c. 0.6% quarter on quarter in Q2-25, but the year is expected to grow just 0.8% in real terms. Positively, Operation Vulindlela continues to provide a roadmap for reform, but progress has been slow and patchy. Structural constraints – including power vulnerabilities and logistics failures, weak municipal capacity, and poor infrastructure delivery – have continued to limit growth. Compounding these structural constraints is a lack of sustained investment. Gross fixed capital formation remains well below pre-pandemic levels, and private sector confidence, while initially buoyed by the GNU outcome, has since waned (Figure 4). We do expect the pace of reform to accelerate with planned investment picking up in coming quarters, but this is more likely to be delivered in late-2026 than before. We expect GDP growth of 1.4% in 2026.

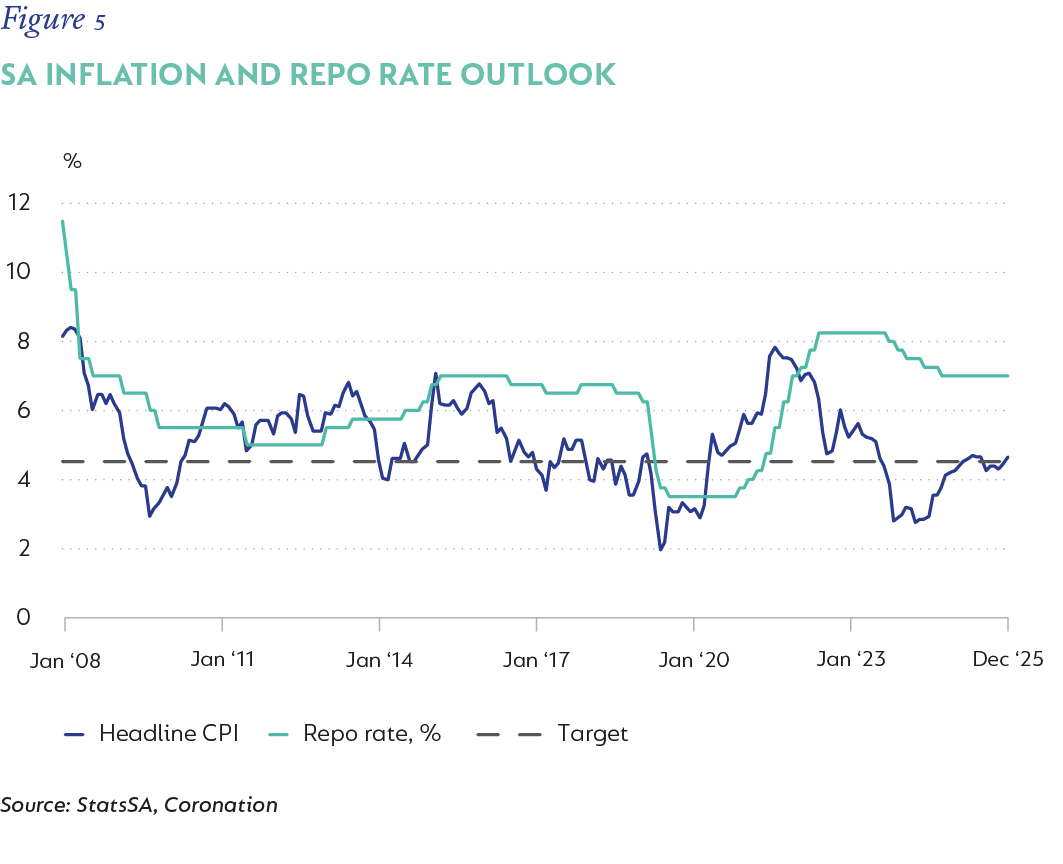

Within the weak growth environment, price pressures remain subdued. Headline inflation has been below the lower limit of the 3%-6% target, and well below the South African Reserve Bank (SARB)’s mid-point objective. Contained food prices, weak core pressures, and the falling oil price have all contributed to the moderation. With this in train, the debate about lowering the target is very much at the fore. South Africa’s inflation target of 3%–6% remains wide by international standards and is considered undemanding by peer comparison. A formal review conducted by the SARB concluded that the current band lacks credibility and is not sufficiently anchored in price stability. A shift to a 3% target – with a narrower tolerance band – could help reduce inflation expectations and the required nominal policy rate. At this stage, we believe the National Treasury is still working on its own assessment, and while it may be opportunistic timing to lower the target while inflation is low, a formal announcement is more likely in late H2-25.

SOME RELIEF FOR BORROWERS

A lower target does not limit near-term opportunity for lower interest rates. The real policy rate has been restrictive for a long time, while growth and inflation dynamics warrant an easier policy stance. We expect inflation to average 3.5% in 2025 and 4.4% in 2026 and see scope for a further 25bp rate cut in July, taking the repo rate to 7.0% (Figure 5).

In sum, South Africa’s weak post-election growth reflects deep-seated structural challenges and an uncertain political environment. However, macro policy refinement – including a lower inflation target, and more clarity on the status of the debate about a fiscal anchor – could provide a foundation for restoring credibility, reducing borrowing costs, and supporting growth, when accompanied by reform execution and greater policy coherence.

CONCLUSION

The interplay between slowing growth, still-elevated inflation, asymmetric monetary responses, and an evolving fiscal landscape will define the second half of the year. With policy normalisation unlikely to be complete – especially in the US – and tariffs adding another layer of complexity, investors may need to reassess the scope for a true pivot. At the same time, the resilience of global growth and the structural AI-led demand story offer some offsetting support. How these conflicting forces balance will determine whether 2025 concludes in a slump (recession?), or a softer landing.

In South Africa, the formation of the GNU was a critical step in preserving democratic continuity – but without meaningful policy execution, it has been insufficient to reignite growth. The structural impediments remain intact: energy, logistics, institutional capacity, and fiscal rigidity, with little evidence of sufficient progress in achieving stronger growth.

Yet within this environment, we see incremental reform efforts as positive and anticipate a modestly more supportive monetary policy stance to lift growth into 2026.

[1] A point where the outlook for long-term growth improves based on a pickup in underlying structural factors in the economy

United States - Institutional

United States - Institutional