Economic views

Emerging markets face a fiscal endgame

Vulnerabilities increase the risk of longer-term damage

- Covid-19 was an amplifier of existing systemic risks in emerging markets

- Recovery certainty around the world is waning as second-wave infections threaten

- Emerging markets will suffer painful growth shocks, but governments’ fiscal positions will be defining

- SA’s economic and fiscal dynamics compare poorly, highlighting the urgency of credible strategies

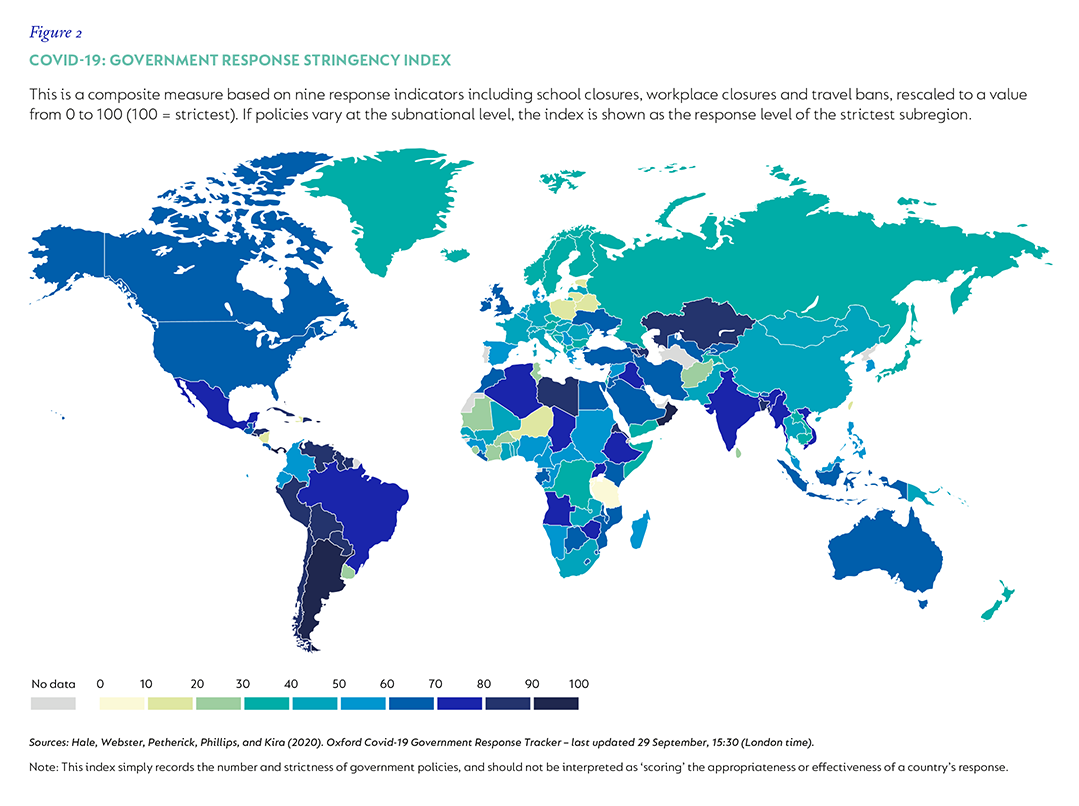

IT’S NINE MONTHS since China imposed a national hard lockdown on its economy. Starting in Wuhan in January, and spreading outwards, by the end of March the borders were closed, streets were empty and factories quiet. Most households could have only one person leave, once a day. The skies were empty. Only China was this strict. While containment was not as harsh elsewhere, there has been some form of closure in most countries as the pandemic spread through Asia, into Europe and the US, and then into antipodean emerging markets.

China’s economic growth bottomed in the first quarter of 2020 (Q1-20), with GDP growth falling by an unprecedented 6.8% year on year (y/y). Since then, Covid-19 infection data officially show that infections have collapsed (12 new daily infections at the time of writing), which means that China has effectively contained the pandemic for now. Mobility data show that China is broadly back to normal – retail, vehicle and property sales, as well as fixed asset investment, are all recovering. Outside of cross-border travel (but including internal travel), China is returning to pre-Covid levels. China is also benefiting from the re-awakening of demand elsewhere, with export growth supported by demand for personal protective equipment and high-end electronics. Official estimates show GDP accelerated to 3.2% y/y in Q2-20, and available activity data suggest decent momentum has built in Q3-20. This should see China’s GDP return to pre-Covid levels by next year, if sustained.

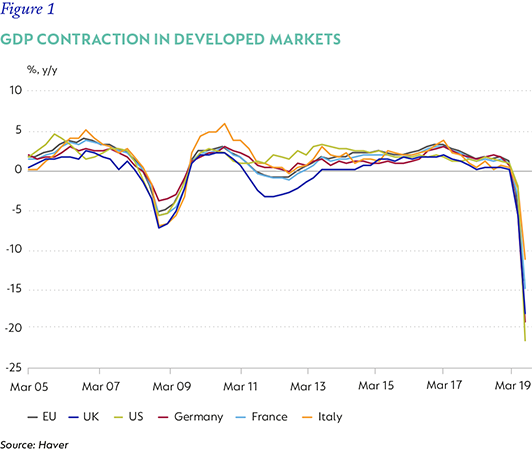

This is not what we see elsewhere. Most advanced economies initially implemented some form of lock-down, and aggressively increased fiscal and monetary support for healthcare systems, households and corporates. Despite this, the severity of lockdown and the associated collapse in activity have resulted in GDP growth contracting 21.5% y/y in the US in Q2-20, 13.9% y/y in Europe and 18% in the UK.

While Q2-20 was undoubtedly the nadir of economic activity for most countries outside China, ‘second waves’ of infection in a number of countries have prevented a return to more normal mobility, and economic activity is slowing again. Both the economic damage and fiscal cost of ‘wave one’ are still unknown as the next wave approaches. Early signs of an economic rebound in the second half of 2020 were relatively good, but momentum has started fading, raising the risk of a Q4-20 ‘double whammy’ as growth falters as containment strategies intensify.

EMERGING MARKET VULNERABILITIES INTENSIFIED BY COVID-19

Within emerging markets, things are even more uncertain because the pandemic is not yet contained. While the efficacy of testing regimes varies greatly, available data show daily infection rates are still rising in many emerging markets and under-testing suggests these could be much higher. An inability to contain the pandemic limits the scope for recovery and raises the risk of repetitive lockdowns. The longer this continues, the more it delays any recovery and increases the risk of longer-term damage.

GDP data in emerging markets broadly mirror what has been seen in developed markets, with a record collapse in activity in Q2-20, and some Q3-20 rebound. But the policy tools that are available to emerging markets to help mitigate the impact of the pandemic on their economies are more limited than those of their advanced peers. So, while the economic impact is likely to last longer and be very painful in emerging markets, with yet-unknown social and political repercussions, the place of lasting vulnerability for most emerging markets will be fiscal policy.

EMERGING MARKET WINNERS AND LOSERS ARE ABOUT RELATIVE FISCAL OUTCOMES

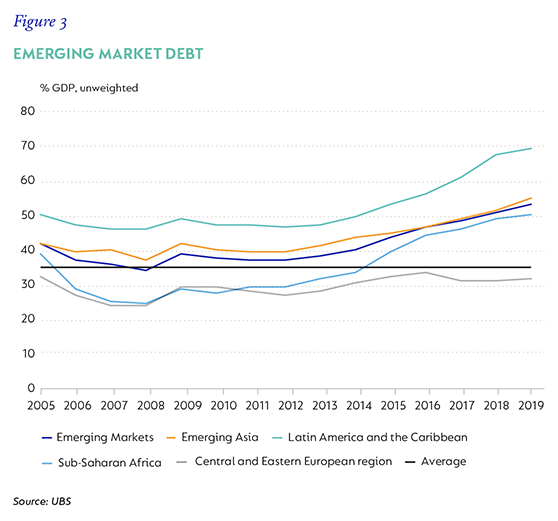

The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic happened when many emerging markets were already fiscally vulnerable – GDP growth was weak throughout 2019 as incomes, profitability and revenues were all under pressure. In many countries, fiscal policy had already turned counter-cyclical, while debt positions were well above pre-Global Financial Crisis levels. Indeed, the IMF estimates that average debt to GDP in emerging markets was 38.8% in 2009, up to 53.3% in 2019 and will add another 20 percentage points of GDP in 2020, as the combination of fiscal support and revenue loss sees deficits balloon and debt ratchet up.

Looking ahead, it’s hard to see any economic ‘winners’ emerging from the pandemic. Many economists talk of economic scarring; the idea that the painful economic injury imposed by the pandemic will have lasting, and visible, effects. There are, however, economies that will fare better in relative terms. Broadly, these will be those with shared characteristics that include:

- the realised ability to grow somewhat faster than prevailing borrowing costs;

- those with lower existing debt stock, which will help keep borrowing costs down;

- those with the capacity to ramp up production for manufactured and industrial goods, should demand (internal and external) recover; and

- those with credible governments, and fiscal and monetary authorities.

This may seem like a wish list. However, economies with these areas of resilience will be better able to attract funding and to sustain low interest rates, which will allow for some recovery in nominal growth. Their currencies should benefit from smaller current account deficits, or surpluses, and low inflation should allow policy rates to remain low. There are relatively few emerging markets that enjoy this happy combination of factors. Among them are China, which for now is already on a path to recovery; some North Asian economies; and Central and Eastern European economies such as Hungary and Poland, which both benefit from their proximity to large markets and access to related supply chains. These countries also have lower starting debt positions, and benefit from lower funding costs.

CASE BY CASE

However, for some of the other big emerging markets, the challenges are varied and significant. I discuss a few below:

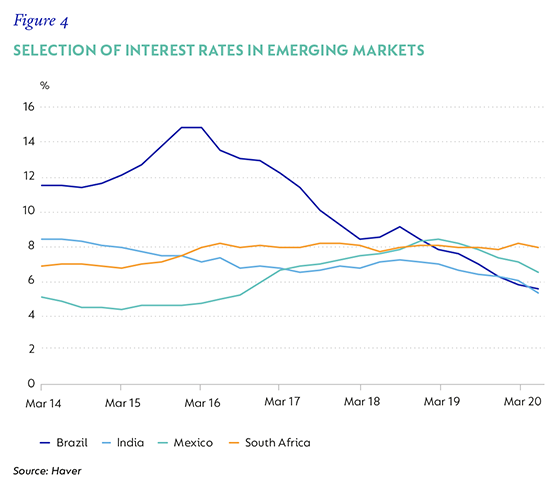

India has not been able to contain the pandemic, and recent infection statistics put India among the most affected countries currently. India was also already in recession when the pandemic hit. Financial sector fragilities have undermined credit lending, and support from the government last year had already helped increase the fiscal high at 72.2% in 2019, and borrowing costs are being contained by heavy support for the government by the national banks. India’s ability to see a strong acceleration in economic activity will be key to its recovery, but while the pandemic spreads and lockdown remains tight, the prospect of recovery is further delayed.

Mexico has also had issues with testing, and unofficial estimates suggest both infection and mortality rates may be considerably higher than official data suggest. Here, too, growth was already weak heading into 2020, undermined by a change in domestic economic policy and the trade dispute with the country’s biggest external source of growth, the US. While some of this risk has receded with the signing of the United States-Mexico-Canadian Trade Agreement, domestic growth strategies are not yet certain enough to sustain a strong recovery.

President AMLO’s commitment to fiscal consolidation, while necessary longer term, has limited fiscal support in the pandemic. This could see Mexico’s fiscal position in better relative shape than its emerging market peers listed here, but ongoing support for loss-making state oil company Pemex is a considerable future risk, as is a slow growth recovery.

Brazil also entered the pandemic on a fragile footing, with slow growth and the highest stock of government debt of the countries listed here, at 92% of GDP. Again, infection rates have not been contained, and government’s pandemic strategy has attracted much criticism. Commitment to pension reform has helped lower borrowing costs, but as growth falters, there is reasonable concern whether this will hold. Here, too, banks have been a considerable support of government’s borrowing needs.

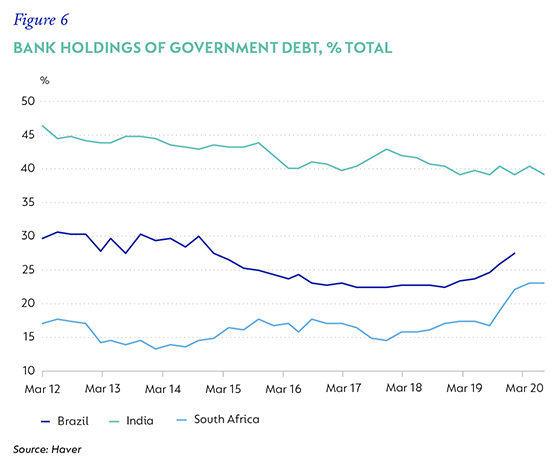

No economy will emerge from this pandemic in a better position than it went in, and for most, the economic challenges that existed before will be exacerbated by the crisis. However, in all the above countries, as in many developed markets, governments have still been able to continue borrowing from financial markets at relatively low interest rates. This is owed in part to globally low yields, especially in developed markets; in some cases, to the direct intervention of the central bank in funding the government; and in other cases, notably in Brazil, India and China, to the State-owned banks buying government bonds.

… WHICH BRINGS US TO SOUTH AFRICA

For now, infection rates have slowed, based on reasonably good testing practice and a hard lockdown early on. But South Africa does not enjoy the mitigating conditions listed above. Instead, it faces a unique set of economic and policy challenges, and very few have been caused by the pandemic:

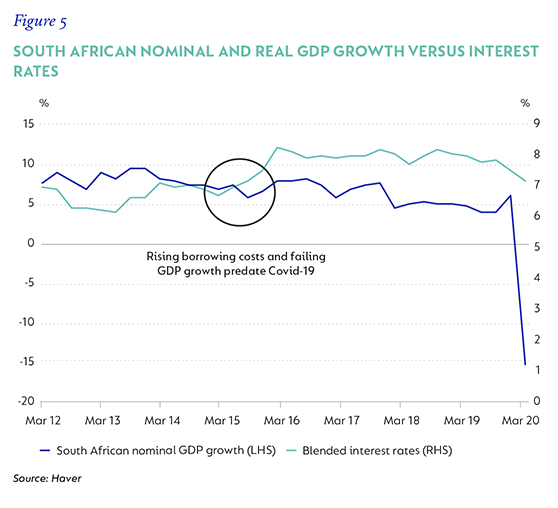

Growth – in real and nominal terms – has been slowing since 2013, when investment started to taper off, undermined by failing confidence, unrest and the reallocation of fiscal resources from investment to wages. As we stand, investment has contracted in real terms in three of the past four years, and took 11.5 percentage points off GDP growth in the Q2-20 crisis depth. Recovery is limited by electricity constraints – South Africa’s global ranking is poor as a result of its unstable energy situation.

Government’s financial position was already vulnerable and increasingly on an unsustainable path, undermined by three things: 1) revenue that was not as resilient as budgeters expected – for the reasons outlined above – and exacerbated by state capture; 2) expenditure, mostly on wages, State-owned enterprise (SOE) bailouts, and increasingly on debt service costs, was unable to adjust fast enough to falling revenues; and 3) economic policy has not been an enabler of economic growth. In addition, unlike several of its emerging market peers, even the riskier ones highlighted above, South Africa does not enjoy low borrowing costs. Despite aggressive interest rate cuts by the central bank, government bond yields remain very high. In fact, the spread between swaps and government bond yields has widened, which means that domestic corporates can borrow at a lower onshore rate than the (supposedly) ‘risk-free’ government can.

This in part reflects the fact that in countries like Brazil (as well as India and China), the local banking system is much more supportive of State financing needs – where there are State-owned banks that own a lot more government debt than is seen in South Africa. They also have much less debt held by foreign investors. But it clearly also reflects the market’s scepticism about government’s ability to put the country and its balance sheet on a more sustainable path. As elsewhere, banks have accumulated government bonds, but they have done so where returns make sense, and they are unlikely to provide the kind of backstop seen elsewhere.

As a result, there have been several calls for the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) to step in and more aggressively accumulate government debt to help alleviate the high cost of borrowing. The SARB has in fact intervened in the market since March but has been increasingly less present as financial dislocations eased. In August, the SARB bought just R350 million of government bonds. Importantly, the Monetary Policy Committee has been at pains to clearly articulate its view that high market rates reflect a long build-up of fiscal risk that does not have a monetary solution.

The biggest challenge is that the underlying debt dynamics are very problematic. Government needs to change the drivers of these, where possible, to ensure a more sustainable policy trajectory. Without this, any intervention will only yield temporary results, if any.

If the SARB intervened aggressively without fiscal commitment to remedy the root causes of its weak position, the risk of foreign investors losing faith is material. South Africa relies on foreign funding, and while holdings have dwindled, they are still significant. In the event that they peter out further, the SARB would have to absorb some or all of the 29.9% of domestic debt foreigners hold, as well as the new issuance. It’s hard to see where that would end, and the SARB understands this – heavy intervention could easily become a Pandora’s policy box.

The currency would be the main casualty, and ensuing inflation would not only further undermine the SARB’s credibility but also efforts to manage long-term rates as the curve reprices. If it’s then forced to raise policy rates (or the market reprices short rates), the fiscal impact may be even worse, given the increase in short-term borrowing that would then need to be rolled.

CONCLUSION

A credible, targeted growth strategy, coupled with a sensible and durable commitment to moderating expenditure growth, is needed to reprice government risk. There are signs that government and its social partners in the private sector, including unions, are working towards this. It is not clear that whatever emerges will be enough, soon enough. There is a healthy and deserved scepticism about the government’s commitment to implementing new fiscal and economic initiatives because there have simply been too many that were either grossly ineffective, poorly implemented, or mothballed.

It may be that the crisis is yet to come. Government’s ability to fund a R700 billion shortfall this year looks as though it will be met. But large consecutive shortfalls in the region of R400 billion to R500 billion will be much more challenging. This reinforces the urgency with which these issues must be addressed, and the steepness of the South African yield curve suggests that within emerging markets, South Africa’s case is among the most critical.

United States - Institutional

United States - Institutional