Economic views

South Africa: The politics of economic reform

- We all know that South Africa needs to grow to deliver the social and economic commitments of the NDP.

- We also know how to do this and have several good, comprehensive policies in place to guide a growth path.

- The recent changes to Cabinet and more pragmatic approach to private sector partnerships demonstrate a marginal shift in the right direction.

- However, politics seems to stand in the way of the country fully implementing these strategies.

IT DOESN’T REALLY matter who you talk to, South Africans agree that we need the economy to grow. Growth really is the most important ingredient in achieving the National Development Plan (NDP)’s stated aims of limiting inequality, reducing poverty, and ensuring a more inclusive economy. Growth is also critical to ensuring the fiscal sustainability that allows government to provide goods and services to those in need, including good quality education, healthcare, and income support. The past decade of growth failure materially damaged our ability to do so, and the pandemic has deepened the hole. In the second quarter of this year, unemployment reached 34,4% - the highest rate ever. President Cyril Ramaphosa’s Cabinet changes and the more pragmatic approach to private sector partnerships are signs that these problems are recognised. To understand whether these slight improvements will bring us closer to the NDP’s goals, we need to unpack the context.

WHY WE NEED FASTER GROWTH

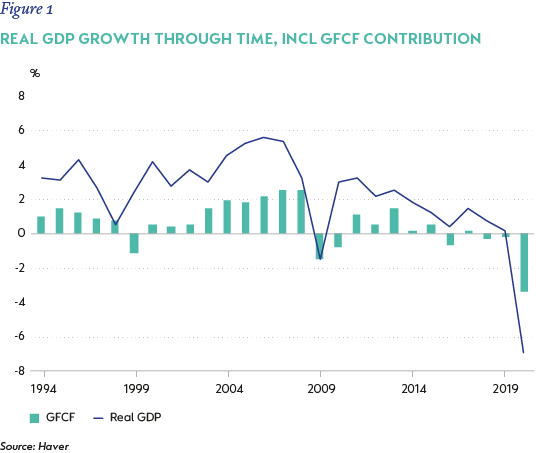

We understand some of the necessary steps needed for us to grow faster. To start, we need to raise the rate of investment. Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) amounted to 15.4% of GDP in 2020, from a decade average of 19% - which was already off-peak. Figure 1 below shows the contribution to the rate of growth from GFCF. Investment typically drives employment and facilitates gains in productivity. Looked at differently, without investment there is little sustainable employment growth and, productivity, which relies on efficient infrastructure, systems, and institutions, fails. Increasing the rate of investment is easier said than done, but we cannot achieve sustainable, inclusive growth without it.

Helpfully, we also have several strategic and well-considered policy documents aimed at delivering precisely this outcome. The NDP 2030 states that in order to raise living standards, we need to increase employment, incomes and productivity, and achieve a social wage and good-quality public services. The South African Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan, presented to Parliament by President Cyril Ramaphosa in October 2020, states clearly that there “is consensus amongst the social partners that there should be substantial structural change in the economy that would unlock growth and allow for development.” It further states that the end goal is to pursue an infrastructure-led economic reconstruction and recovery that will stimulate various sectors of the economy.

Former Finance Minister Tito Mboweni’s “Towards an Economic Strategy for South Africa” lists the fundamental building blocks needed to raise long-term growth. He highlights the need for specific and “deliberate” actions across a range of fronts, specifically identifying that the growth reform agenda needs a five-pronged approach including both practical and ideological shifts in the direction of policy. The five drivers are 1. modernising network industries to promote competitiveness and inclusive growth; 2. lowering barriers to entry and increasing competition; 3. prioritizing labour-intensive growth; 4. implementing flexible industrial and trade policies to improve competitiveness; and 5. using regional growth to promote export competitiveness.

These five priorities explicitly address significant hard and soft inhibitors of growth - and this is where the politics comes in.

WHY DID GROWTH FAIL?

Average real GDP has been just over 1% per annum for a decade. In real per capita terms we have gone backwards. Tempting as it may be to blame political failure (and many politicians should be held accountable), the answer is more complicated. In part, there are some very practical challenges which are intertwined with more nebulous, and, at times nefarious, influences that are harder to overcome.

The past decade’s growth stagnation was the result of a complex set of interwoven events, policy decisions and both intended and unintended related consequences. In 2008, South Africa ran out of electricity. Rolling blackouts have been undermining our output since then and have had a devastating impact on productivity. In the period to follow, uncertain energy availability was joined up with a significant increase in political uncertainty.

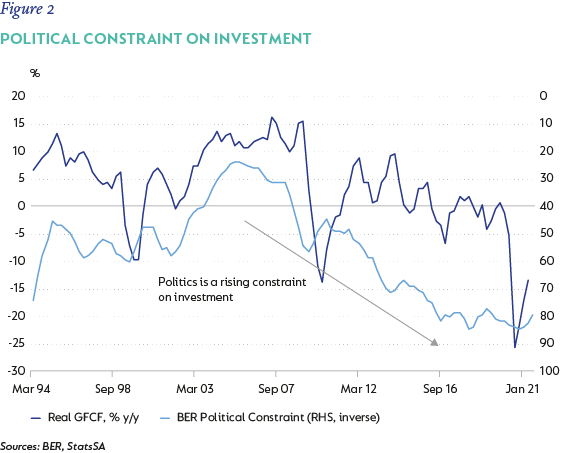

The combined burden of political uncertainty (an umbrella term for all the political unknowns, charters, regulatory changes and Cabinet reshuffles, to name a few) squandered resources, unnecessary red tape, an incapable State, inflexible labour markets and the systemic failure of State-owned companies to deliver on their mandates, all materially affected costs, sentiment, and economic opportunity. Investment slowed and productivity collapsed. Getting even some of these ingredients right should go a long way to reducing another critical constraint on investment – the high borrowing costs which reflect growing wariness about the sustainability of governments fiscal position (figure 2).

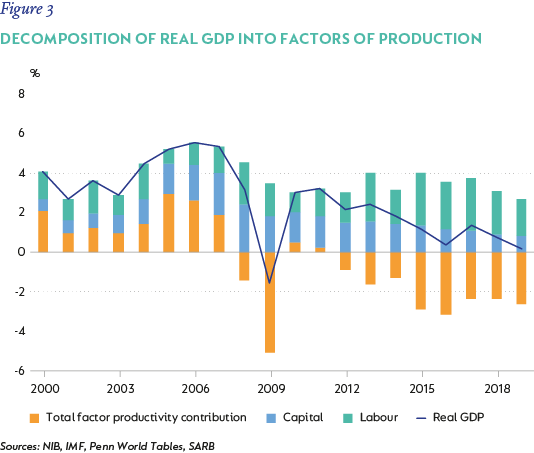

If we decompose the GDP growth of the past decade into factors of production, as illustrated in figure 3 below, we can see that through time, periods of high capital growth (investment) have been accompanied by strong gains in both employment and productivity. The collapse in investment since 2012 has seen a persistent loss of productivity, which in turn was a material detractor from GDP growth. Employment was stickier as the State expanded the civil service, but the contribution from the private sector also fell. This dynamic is not sustainable.

If we could add back the productivity growth lost since 2009, real GDP could have compounded at an annual rate of 3.3% (from 2009 - 2019) over the past ten years, instead of the 1.7% we achieved.

The role of political leadership in achieving better growth outcomes by addressing these elements cannot be emphasised enough. Cabinet’s ultimate role is to create the enabling legislation required to ensure its departmental objectives are met and that they align with a national agenda (currently the NDP). Ministerial clusters (such as Infrastructure Development, Economic and Employment, Governance and Administration) are supposed to ensure the alignment of government-wide priorities and to facilitate and monitor the implementation of priority programmes. Despite pockets of great effort, there has been very little success in this regard. So, when President Ramaphosa announced his new Cabinet at the end of July 2021, the expectation was that - following the slowing in growth recovery in the second quarter of 2021 and the July unrest - new emphasis and capacity would be given to the leadership of critical Departments.

NOT SO FAST

When measured against the five priorities for achieving better growth, the reshuffle, and the events which followed provide mixed evidence of delivering on the commitments of the NDP. We have a new Minister of Finance, which arguably we didn’t need. But former Minister Mboweni has always been clear that his participation was temporary, and Minister Enoch Godongwana may yet bring much-needed energy to the hard-working souls at the National Treasury. Understandably, his style will differ from Mboweni’s, but, in his words, the “direction of travel will be the same”. He is likely to focus on growth, committing publicly to an active growth strategy that is focused on public investment in infrastructure, accompanied by structural reforms. If he holds the line on current expenditure (wages), an in-the-trenches approach to boosting growth is to be welcomed. We need both growth and expenditure consolidation to reduce long-term borrowing costs and help achieve the economic and social commitments of the NDP.

The appointment of a new Minister of Communications and Digital Technology is an opportunity for great improvement. Minister Khumbodzo Ntshavheni is expected to free spectrum and facilitate better communications capacity. Addressing degradation of critical national water and sanitation infrastructure will take time but capacity here too should improve with Mr Senzo Mchunu as the new Minister of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation.

But only three new ministers were appointed, and only two were fired (to have one reemerge in a more senior position). Elsewhere, there is not yet a visible shift in narrative. Incumbent ministers have not noticeably moved to align with the other actions, and there hasn’t been much reduction of red tape, any move towards reform of labour legislation, or the active facilitation of increased competition. Embedding these actions requires a new way of thinking, and it seems as though the Cabinet is still largely staffed by old thinkers.

More broadly, the amendment of regulations governing the embedded generation limit increase is slowly emerging, but still feels like a reluctant move, and much is still uncertain. Along similar lines, the announcement that Transnet will seek private partners to help run its ports is encouraging – and an acknowledgement of the need to introduce private efficiencies – but, again, comes with great uncertainty not only about the current state of these entities and their component assets, but also the terms on which such partnerships may operate. Although these moves are encouraging, they remain opaque. It is hard not to be just a little wary of undue optimism.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR GROWTH GOING FORWARD?

We need to acknowledge that the staggering unemployment rate is a crisis. Achieving growth at rates we have foregone in the past is the least we need to start to address this tragedy. Recent moves are a start – enabling energy production by the productive sectors should add considerably to growth momentum, both investment, overall output and by improving confidence. A more pragmatic approach to the private sector’s involvement in the provision of critical network services is another positive move, but we need to embrace all five drivers of growth, quickly, to have a chance of achieving the goals of the NDP. +

Disclaimer

United States - Institutional

United States - Institutional