Investment views

Bond outlook

Hope must make way for action

The Quick Take

- 2022 proved a tough year for investors as global macro events saw global bonds and equities down significantly

- Globally inflation is on a downward trajectory; SA likely to follow suit with prevailing conditions supportive of a lower repo rate next year

- SA’s position remains precarious; accelerated policy reform and private sector economic participation are essential to achieve the growth needed

In the Chinese zodiac, 2022 was the year of the ‘Water Tiger’. Tiger years have the potential to be explosive, since, by their nature, the Tiger is a ferocious, impulsive, and quick-tempered animal. In retrospect, financial markets didn’t diverge much from this prognosis. The combined effect of the Russia/Ukraine war, aggressive monetary policy normalisation and the lingering effects of Covid-19 yielded a bleak landscape for investors. This precipitated a fall of c. 18% in both global bonds and equities during the year.

South Africa (SA) fared relatively better than its counterparts during much of the year, despite the worst bout of loadshedding on record. December, however, brought fresh political concerns as the ‘Farmgate‘ scandal threatened to derail President Ramaphosa’s presidency and his campaign for a second term as ANC president. Fixed income instruments recorded a torrid year, with the entire local asset class underperforming cash, which returned 4.82%, over the period. SA 10-year bonds closed the year at 10.86%, almost 100 basis points (bps) higher than the close at the end of 2021 and a level not seen since the onset of the Covid crisis in March 2020.

Despite a high starting yield, the FTSE/JSE All Bond Index (ALBI) generated a total return of 4.26%, which was not only below cash but also marginally behind inflation-linked bonds (ILBs) that delivered a total return of 4.54%. In dollars, the ALBI was down 2.38% in 2022, which is significantly better than global bonds, with the FTSE World Government Bond Index down 18.26%.

2023 is the year of the ‘Water Rabbit’, which is a sign of longevity, peace, and prosperity in Chinese culture, meaning 2023 is predicted to be a year of hope. South African’s have been holding onto hope since President Ramaphosa took over the helm of the ANC in 2017 and the country in 2018. However, the pace of reform implementation has been disappointing and, if it were not for some very good luck over the last two years in the form of higher commodity prices and the restatement of GDP to a higher base, SA might well have found itself in a debt trap.

HANGING IN THE BALANCE

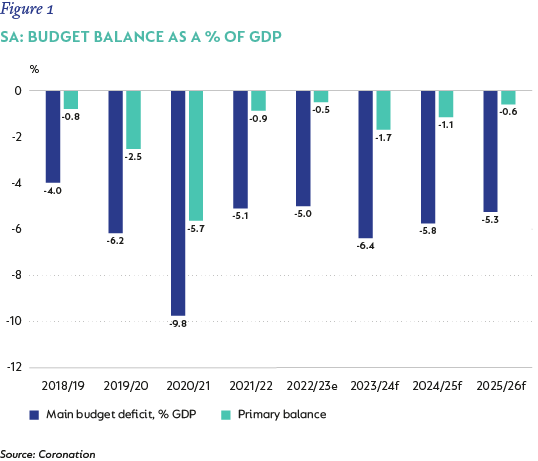

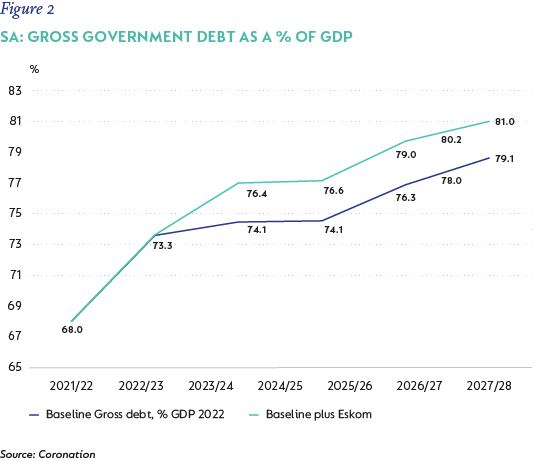

Government finances remain delicately placed as the primary balance is expected to stay in deficit until at least 2025/2026, reaching a debt load of c. 80% of GDP (refer figures 1 and 2). Financing costs remain well above nominal GDP and the only permanent solution is for the country to generate real economic growth of between 2.5% and 3.0%. That level of growth cannot be generated by government alone and reforms need to be accelerated to allow the private sector into the economy in a more meaningful way. In the energy sector, private generation can reduce the pressure on Eskom and increase the growth potential of the economy.

Other critical infrastructure such as roads, rail and water are in dire need of renewal and current government finances are not well placed for the magnitude of spending required. The private sector has the expertise, willingness and means to alleviate the pressure on government and increase employment opportunities in the economy through these projects. The ANC elective conference in December 2022 has bolstered the hold that President Ramaphosa and his allies have on the ruling party. Let this year’s hope be that the time for talking has passed and the time of doing is upon us or else the financial projections below could also become a mere hope.

INFLATION SET TO SUBSIDE

Global inflation and growth are widely expected to decelerate this year. US inflation, which was stubbornly high over 2022, is expected to average 4% this year from 8% in 2022. SA inflation should also follow a similar path and return to the midpoint of the band by end 2023 and is set to average 5.2% in 2023. The market’s expectation for the repo rate has also moderated, with a peak of 7.5% in the first quarter of 2023 (Q1-23), with no cuts priced until early 2024. However, SA growth is expected to decline from above 2% in 2022 to around 1% for 2023.

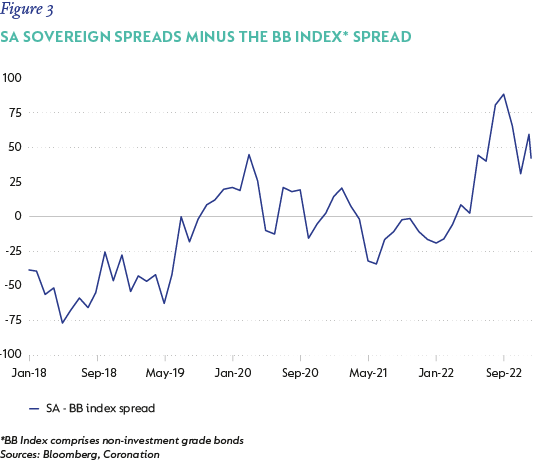

The combination of decelerating global inflation, local inflation closer to the midpoint of the range in the fourth quarter of 2023 (Q4-23), and below-trend growth should, however, start to see expectations for a lower repo rate by end 2023. We view a normal repo rate in the rate of 6.5%-7%, which implies the start of a gradual easing cycle in Q4-23. Despite this normalisation in front-end rate expectations, SA 10-year government bonds still trade at quite elevated levels. The implied credit spread for SA bonds still trades at around 50bps above their equivalently rated counterparts (Figure 3).

SA’S YIELD CURVE - A DIVERGENCE

The SA yield curve remains an anomaly. Beside the fact that yields remain very elevated relative to cash, the SA yield curve remains among the steepest yield curves in the emerging market universe. A key reason for this is the fact that National Treasury continues to issue in the very long-end (>10 years) area of the curve due to the fear of being unable to roll over debt in the event of a crisis. The weighted average maturity of outstanding debt in SA remains among the longest in the world, at 11.34 years. This is significantly better than some developed market countries such as the US that has an average maturity of 6.04 years.

Credit spreads in SA remain very tight due to reduced issuance and an abundance of cash looking for a pickup relative to short rates. National Treasury did issue R50 billion of floating rate notes (FRN) in 2022 to supplement their issuance programme at levels of three-month Jibar + 130bps (currently trading in the market at three-month Jibar + 75bps). Even assuming cash stays at 7.5% and they are forced to issue at credit spreads of 130bps above cash, this still equates to a level of 8.8%, which is almost 2% lower than where the current 10-year bond trades. Another hope is that we see more use of the FRN programme to substitute for current fixed rate issuance, which could reduce the pressure on the 10-year area of the yield curve.

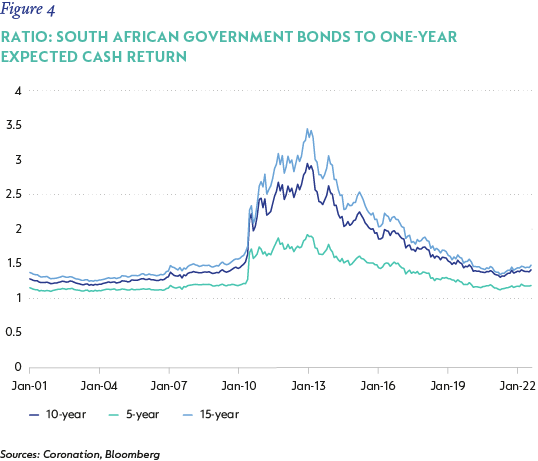

Figure 4 illustrates the ratio between the yields on various bonds (five-, 10- and 15-year) relative to expected one-year forward cash rates. It is clearly observable that the ratio between five-year bonds and cash have returned to pre-Covid levels, however 10- and 15-year bond ratios to cash remain elevated. Historically, 10-year bonds have generally traded at a 10% premium to the five-year ratio. Even if we assume that should now be double, given the deterioration in fiscal accounts, and assume cash in one years’ time will sit at 7%, then 10-year bonds should trade somewhere in the range of 9.5%-10%.

These two simple arguments on SA’s implied credit spread and the shape of the yield curve lead to the conclusion that SA 10-year bonds remain attractively priced and should trade in the range of 50bps to 100bps lower from a yield perspective.

SA CORPORATE CREDIT CURRENTLY UNATTRACTIVE

Corporate credit is an incredibly effective tool that can be used to enhance both the yield and longer-term performance of fixed income portfolios. However, it is important to understand that yield is earned over a multi-year investment horizon, and a long-term focus is essential when analysing and investing in the asset class.

The SA credit market is more nuanced than international credit markets, with significantly lower issuance and hence much lower liquidity, making it predominantly ‘buy and hold’ in nature. This accentuates the need for the rigorous interrogation of credit quality and appropriate compensation in valuation for holding these instruments. In the years following the Global Financial Crisis, credit has been employed as a significant driver of fixed income portfolio returns, but the types of instruments employed have become more complex and less transparent with regards to the actual risk they carry. This requires investors to spend more time scrutinising not only the credit quality of their investments, but also the instruments through which they lend to these entities.

We believe that the corporate credit spreads currently on offer are not attractive, and do not reflect their inherent risks. As such, we have been allocating away from credit and allowing our investment in credit to become less material in our portfolios for quite some time. However, with the recent repricing of global rates and credit markets, we believe these offer an attractive opportunity for investors.

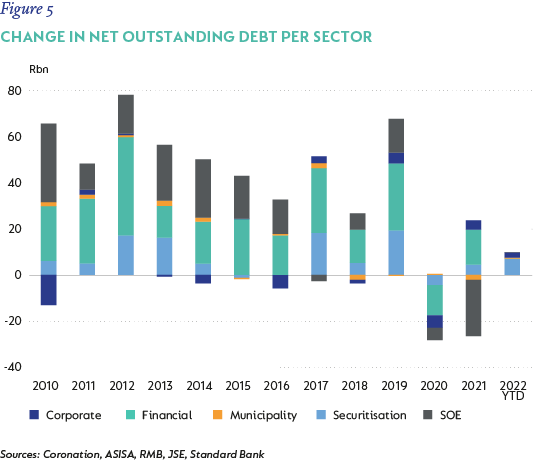

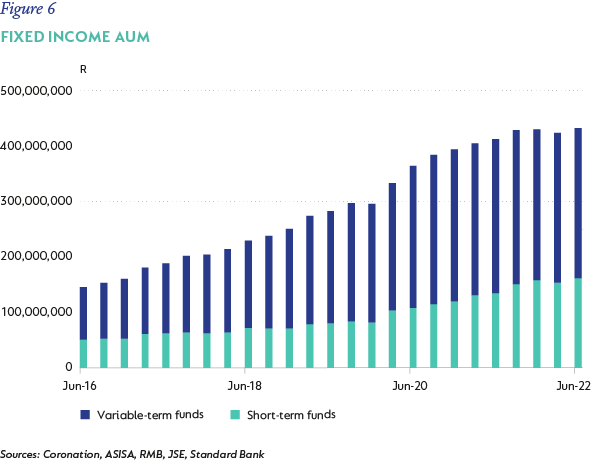

The local credit market has been influenced by a shortage in supply and an increase in liquidity. Issuance this year has been net negative, and according to data from the Association for Savings and Investment South Africa (ASISA), savings continue to accumulate. A supply/demand imbalance of this magnitude continues to distort fundamental credit pricing (see figures 5 and 6).

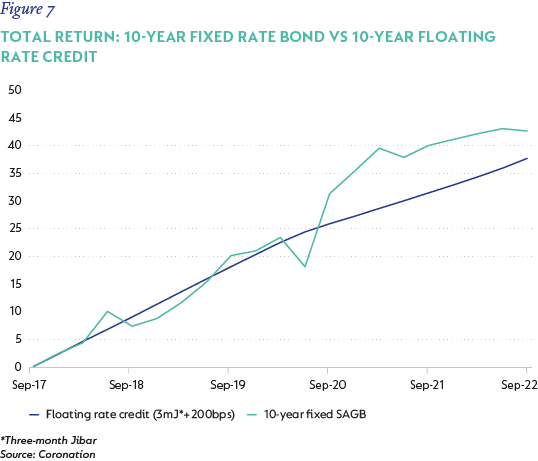

In our view, SA government bonds (SAGBs) offer a much better allocation opportunity, albeit with more volatility Figure 7 shows that over the last five years, fixed rate bonds have comfortably outperformed floating rate credit for investors who have been willing to stomach the additional volatility.

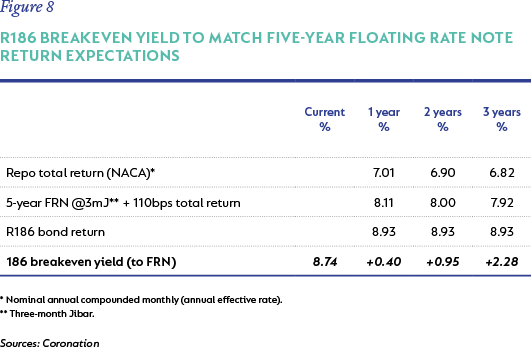

And, going forward, we still firmly believe this to be the case. If we look at the expected returns of a five-year government bond versus a five-year bank credit instrument set out in Figure 8, government bond yields would need to widen significantly over the next three years to underperform.

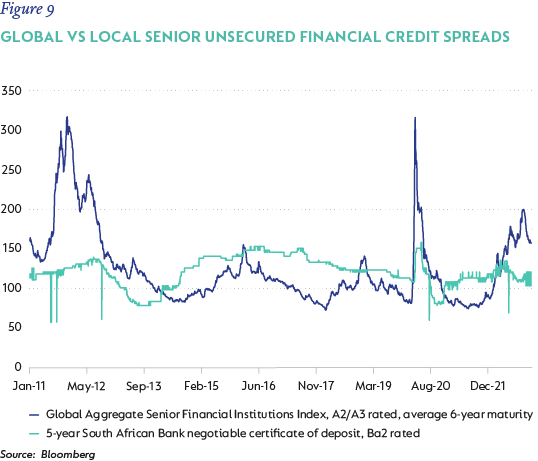

Offshore credit is an asset class where we can achieve better returns for similarly priced risk. Figure 9 shows that better rated, international banks are trading at a wider credit spread relative to our domestic bank issuance. In a year where risk assets have been roiled by market turmoil, SA bank credit spreads have tightened.

Low levels of issuance and tightening credit spreads have created a guise of safety when it comes to investing in the local credit markets. We believe that allocating significant amounts of capital to the local credit market is unwise and would represent a substantial opportunity cost in the face of attractive valuations in other, more liquid asset classes. SAGBs and offshore credit markets, despite being more volatile, offer considerably better prospects over the longer term.

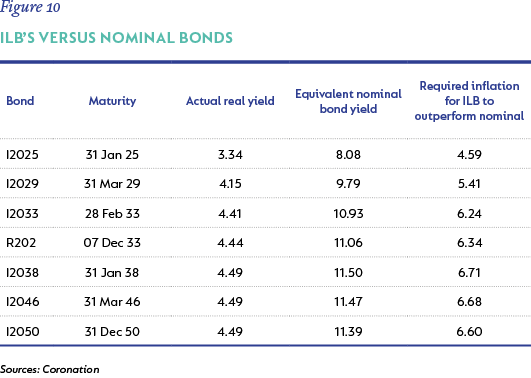

ILBs, like nominal bonds, continue to trade at elevated levels. One can attain returns of between 3%-4.5% after inflation when investing in the SA ILB market. In a world of cheap valuations, the limiting factor is cash and one has to be careful, as with credit, when assessing the relative attractiveness of the various asset classes. Although the real yields on offer are quite attractive, the required inflation for ILBs to outperform nominal bonds remains high, specifically for ILBs with maturities of greater than six to seven years (I2029) – see Figure 10. We therefore continue to favour ILBs with a maturity of less than seven years for allocation within a bond fund.

THE YEAR AHEAD

The global environment will remain in state of flux for at least the first half of 2023 as the battle between monetary policy normalisation, slowing global growth and sticky inflation continues to wage on. Risk sentiment has recovered slightly since the severe bout of risk aversion in the second half of 2022, but SA faces its own challenges – both politically and economically. Loadshedding, crumbling local infrastructure and souring local sentiment have precipitated the need for swifter reforms and increased private sector involvement. The valuation of SAGBs should provide a reasonable buffer, as they have been already, since they trade at significant discount to fair value. We continue to advocate an overweight position in SAGBs, low or no allocation to corporate credit and believe short-dated ILBs still warrant a place in portfolios.

Disclaimer

SA retail readers

SA institutional readers

Global (ex-US) readers

US readers

United States - Institutional

United States - Institutional