The importance of institutions - July 2016

It is hard to deliberate on the key constituents of a functioning society and economy when you are hungry. And it is even harder to believe in the importance of these institutions when the same society or economy has failed to provide you with an education, or a job, or the means with which to feed your family.

There is a wide range of institutions that support societies, incorporating structures that defend property rights and the legal framework, including the court system; the political system and the framework within which government operates; institutions which regulate economic and financial stability; and those that provide social insurance and safeguard security (including the police and military). As such, these institutions make up the fabric within which citizens, businesses, political parties and the economy operate, and provide a framework of rules, social norms and understood processes that are both explicit and implicit.

State institutions are an economy’s primary facilitator of social and economic development. Research shows that these institutions can be a major source of growth; effective institutions aid investment in physical and human capital, in research and development, and in technology. Institutions also have an important redistributive role to play in the economy – they make sure that resources are properly allocated, and ensure that the poor or those with fewer economic resources are protected. They also encourage trust by providing policing and justice systems which adhere to a common set of laws. Properly functioning institutions are a signal of a well-managed economy, enabling governments – and businesses – to borrow money more cheaply. In turn, higher growth and lower borrowing costs give governments the resources to spend on social needs as well as on investment into infrastructure, health and education.

The reverse is also true. Failed or ineffective institutions undermine trust, raise the cost of doing business and increase the cost of government borrowing, limiting the ability of government to spend. If a government does not carefully manage its expenditure, rising borrowing costs can quickly lead to a debt spiral from which recovery is difficult, and where everyone suffers, but the poor the most.

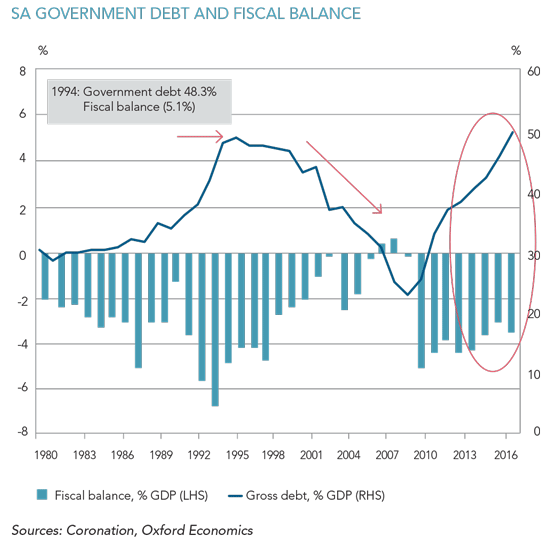

One of the biggest challenges for the first democratic government in SA was stabilising and reinforcing a very weak economy. The government inherited an enormous stock of debt and a budget framework with persistently large deficits. Ongoing massive government spending fuelled a large external deficit too, and the currency was vulnerable and prone to weakness. Inflation was rampant and interest rates volatile. Wealth and economic resources were highly concentrated along racial lines, and for the majority of the country, basic needs were not met. All of these issues reflected a failure of state and economic institutions under the apartheid government.

At the time, the ruling ANC government took the tough decision to rein in spending, to recapitalise the state pension fund (which had been plundered), and to create a transparent long-term budgeting process which anchored fiscal policy to a sustainable path.

A new constitution helped provide the framework for other institutions, and a commitment to growing, entrenching and protecting these institutions helped restore confidence and steered the economy onto a better growth path and a fiscally strong position. Over time, this commitment helped lower funding costs. Ratings agencies acknowledged the progress and upgraded their sovereign ratings for SA well into investment grade. The state was now able to spend on social grants, to provide basic services to the poor, to reduce its debt and fund its spending at more reasonable levels.

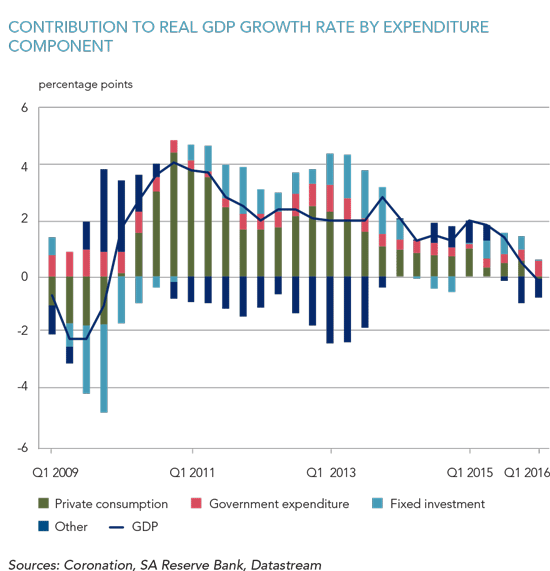

There has been considerable slippage in some economic institutions since the global financial crisis. Fiscal policy has much less flexibility because after government increased spending to alleviate the impact of the recession, it never really reduced it again, borrowing in order to finance the spending and adding steadily to the country’s debt stock. Consolidation of the deficit has been very slow because expenditure – mostly on wages – has grown so fast.

Policy uncertainty has also played an important role in undermining the effective functioning of domestic institutions; ranging from delays in the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Act, uncertainty about a possible (though likely) national minimum wage, conflicting information about the status of the nuclear programme and state policy on electricity provision, as well as the effectiveness of state-owned enterprises. This can be seen in very weak employment growth (outside of the state), and the slow recovery of private sector investment.

A range of challenges – from unemployment, poverty, inequality, Eskom’s capacity constraints, the ability of the state to provide adequately for the ravages of the drought, to disastrous decisions around tourism policy, immigration and emigration – have fuelled social unrest and service delivery protests, which have intensified as the economy struggled to grow. These are all reflective of institutions which are not functioning effectively.

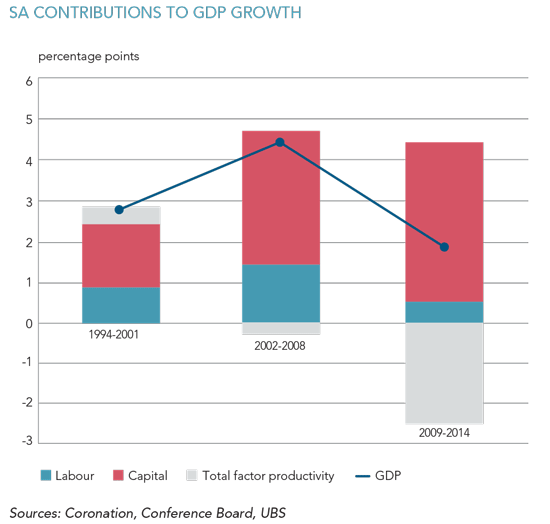

Against this backdrop, it is unsurprising that SA’s economic growth has slowed so much, even without the devastating drought and the negative impact of falling commodity prices on the mining sector. The long-term drivers of growth – capital expenditure, employment and gains in productivity – have all weakened and remain markedly below the precrisis levels. Ratings agencies responded to an increase in sovereign risk with downgrades to SA’s outlook at the end of last year.

There is a glimmer of light. National Treasury has managed to consolidate its fiscal deficit, beating its 2015/2016 fiscal target of -3.9%, and delivering a deficit of -3.3% despite the weakness in economic growth. A hard line on expenditure helped. National Treasury is also overseeing a number of programmes to remove the constraints on doing business, including a review of port tariffs, concessions on the new visa requirements, tender and procurement reviews. All of this should help. Elsewhere, Eskom has managed to increase both maintenance and capacity, eliminating blackouts and the associated disruption on economic output. A review of labour market constraints – notably introducing ongoing negotiations to agree on a strike ballot – is underway. These efforts have been enough to stave off ratings action from all three agencies, and kept the country’s sovereign ratings just inside the limits of investment grade.

It is clear that the effective functioning of SA’s institutions is a crucial precondition for economic growth. The vagaries of factors such as weather, global shocks and commodity prices cannot be avoided, but institutional strength is the responsibility of all people in a democratic system. The path to sustainably raising economic growth is littered with tough choices, and the process is not easy. But history shows us that there is no more effective way of helping societies improve the lives of their members, especially those most vulnerable, than through economic growth.

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional