Quarterly Publication - October 2017

Bond Outlook - October 2017

The performance of many fixed-income asset classes over the last quarter has masked increasing divergence in longer-term market expectations, resulting from heightened levels of uncertainty. Uncertainty is a familiar bedfellow of investors, and increased uncertainty historically manifests itself in asset prices. SA finds itself at the arduous intersect of extraordinary global and local uncertainty. Globally, the direction of monetary policy, the impact of unwinding quantitative easing and increasing political disruptions continue to obscure the macro picture. Locally, the outcome of the governing party’s leadership race and more importantly, its effect on policy implementation, remain crucial for the struggling local economy. Despite all of this, SA assets have continued to defy the gravity of local fundamentals.

This past quarter saw the All Bond Index (ALBI) gain 3.7%. Its returns for the year to date and over a rolling one-year period, at 7.8% and 8.2% respectively, are both well above cash. While the yield of the long-term section (12 years and longer) of the ALBI is well above 9.5%, it has been the three to seven-year area of the bond curve that provided the best performance year to date and over 12 months. The shorter end of the bond curve has been anchored by expectations of a lower repo rate, which was eventually cut in July.

In addition, strong emerging market bonds have buoyed local bonds. Over the previous quarter, the ALBI’s performance in dollar (-0.6%) was behind that of the JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index (+2.4%). Still, the ALBI’s performance year to date (+7.8%) is in line with emerging markets (+8.8%). Over a rolling one-year period, the ALBI (+9.1%) is far ahead of the emerging market index (+4.2%). SA’s high yield relative to its emerging market peers has helped attract foreign capital and prevented any material widening in yields (capital loss), thus far.

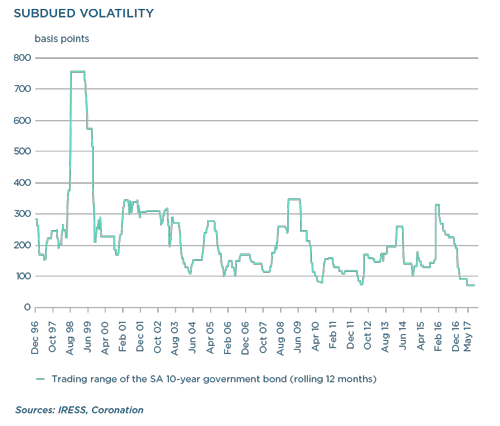

The SA 10-year benchmark bond started the quarter just above 8.8%, touched a low point of 8.4%, but spent the majority of the quarter between 8.5% and 8.6%. Despite the elevated levels of uncertainty, bond yields have not been volatile. Over the last year, the benchmark bond’s trading range (the difference between the highest and lowest traded yield) has narrowed steadily to below 100 basis points – the lowest level in the last 20 years. This hardly seems to reflect a high level of uncertainty.

There are a few interlinked reasons that explain these low levels of volatility in the local bond market. First, it is important to distinguish between volatility and uncertainty. Volatility occurs when uncertainty suddenly materialises in definitive actions that impact asset prices. Since the Nenegate crisis, there has been an increase in uncertainty, but not an increase in definitive policy actions that have had an actual impact on underlying asset prices. Also, the market holds very different views on the implications of possible policy actions, providing very little guidance as to how asset prices should/could behave.

To us, the major concern is that the prolonged lack of definitive policy actions will further undermine a lacklustre economy, eventually triggering a stark reaction from the market. At the moment, the current subdued volatility is feeding an underlying complacency about possible market outcomes. Over the last year, low levels of volatility have allowed investors to safely earn the yields offered by local bonds. But stability begets instability – investors extrapolate current stability and expect that things will always remain fine. The slightest unexpected negative event may then trigger an overreaction, and the ultimate outcome may be much more dangerous. There is only one way to protect our investors against this risk: by only investing if the underlying assets are cheap enough to withstand any short-term deterioration in fundamentals and/or volatility.

So, are SA bonds cheap enough? One way of determining the fair value of SA government bonds is by doing a calculation (demonstrated below) featuring the global risk-free rate (US 10-year bond rate), the inflation premium required when investing in local assets (the difference between expected SA and US inflation) and the riskiness of SA as a borrower (SA’s credit default spread).

All inputs used in the following calculation come directly from the valuations implied by the markets. For instance, the 10-year US and SA inflation rates are implied by the 10-year nominal and inflation-linked bonds.

It is evident that SA government bonds are expensive relative to their fair value. One could argue that market expectations for SA inflation are too high and should be closer to between 5.2% and 5.5%, but similarly, the current level of the US 10-year bond probably should also be higher (perhaps 2.8% to 3%), given the impending unwinding of the US quantitative easing programme. Also, the absolute level of the SA credit spread may require extra scrutiny: the current level could be more reflective of the global ‘risk-on’ environment, and not SA’s precarious fiscal situation.

The key takeaway remains that SA government bonds are somewhere between fair value and expensive. In the short term, the global backdrop remains supportive, with growth pushing higher, inflation heating up (but contained) and global yields remaining complacent. However, local valuations do not offer any margin of safety against bad news. It is therefore difficult to justify a long/overweight duration position in the SA 10-year bond yields.

So why are SA 10-year bond yields continuing to trade at more expensive levels?

To start with, the market expects more interest rate cuts. Consumer inflation has moved lower and is expected to remain well behaved over the next two years. Meanwhile, the faltering economy is growing well below its potential, which has lowered both the SA Reserve Bank’s and the markets’ expectations of short-term rates in the first half of the year.

Following the SA Reserve Bank’s repo rate cut in July, the market expects the repo rate to move lower by another 0.5% over the next six to nine months. This has enhanced the attractiveness of SA bonds relative to cash and acted as a strong anchor for the bond market, keeping the upside on yields well contained. There has, however, been a much larger force keeping SA bond yields trading at expensive levels.

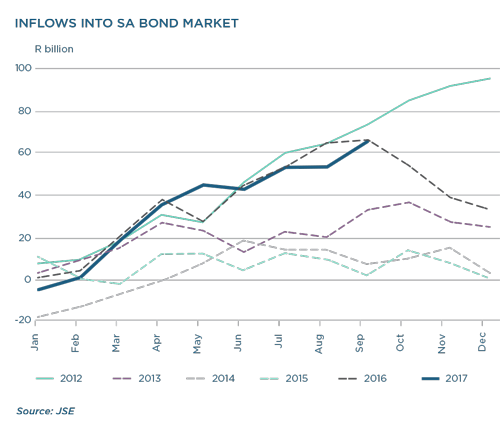

Foreign inflows into the local bond market have been substantial this year, at approximately R70 billion. This ferocious buying spree is almost on par with the pace of accumulation seen in 2012 when SA was included in the Citigroup World Government Bond Index (WGBI). But in 2012, the outlook for the economy was much better. In addition, SA’s credit metrics were much healthier and among the strongest of its emerging market counterparts, whereas now SA is staring down the abyss of subinvestment grade.

SA is currently benefiting from a flow of capital towards emerging market bonds. The market expects that global inflation will undershoot targets in the shorter term, that the unwinding of quantitative easing will not have much of an impact and that developed market bonds will remain well behaved. Unfortunately, all of these assumptions are based on shorter-term outcomes that can dissipate quickly. Market expectations for US rate hikes are still materially below what the Federal Reserve (Fed) is guiding – to such an extent that the current market pricing of the long-term Fed target rate is 1% below the Fed’s own guidance (1.75% versus 2.75%). Investors are buying emerging market (and SA) bonds because they offer much higher yields, but the underlying assumptions about US yields are either very stretched or at risk of being too optimistic.

Also, consider that if SA were to be downgraded to below investment grade, it could result in the mandated selling of R120 billion to R150 billion worth of SA government bonds by passive trackers of the Citigroup WGBI. It is quite difficult to see the current pace of inflows continuing to contain yields if that event were to occur – especially in light of the fact that the SA government also needs to fund itself to the tune of R180 billion to R190 billion every year. Foreign inflows need not reverse, but just abate, for the yields of SA government bonds to succumb to the supply dynamics.

The underlying mix of factors driving the current level of yields in the SA bond market is concerning. Low volatility has increased complacency, supported by aggressive shortterm inflows into the bond market. This has created an eerie feeling of stability despite a steadily deteriorating local backdrop. Meanwhile, the international environment is becoming less friendly for carry trades. Yet investors continue to revel in delusions fuelled by the accommodative global monetary policies of yesteryear.

Local bonds are at levels deemed to be on the expensive side of fair value, and do not offer a sufficient margin of safety if one of the short-term supportive factors should fall away, or the economy suffer a further deterioration. We remain cautious in our approach to investing in the local bond market. Only when bond yields are cheaper than fair value and offer an adequate buffer against expected adverse volatility will we look to deploy capital meaningfully into the asset class.

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional