Business & Industry views

Making value judgements

When it comes to your retirement fund, are you receiving good ‘value for money’? How would you even know?

- The retirement industry is about delivering value for money to its members

- Assessing value for money is not an exact science – informed judgement is required

- Costs are critically important and should be commensurate with the scope and quality of service provided

- Regulation, consolidation and improved transparency have increased our understanding of both value and cost

VALUE FOR MONEY (VFM) is ultimately about deciding whether the benefit (i.e. the value) of buying something justifies the cost (the money). But we know that making VFM decisions is almost never straightforward. If you are buying a new smartphone, do you go for the cheapest option that does the job, or do you pay more for one with better features? What features are important to you? Is it size, build, battery life, display, camera, or perhaps it is the brand? And once you have an idea of how features compare, how do you weigh these up to decide which phone is best for you, given your needs and the price?

A RELATIVE GAME

With any purchase, value is in the eye of the beholder. Creating a shortlist is usually easy – discard the items that don’t have the features you need and the ones that are unaffordable. But once you have that shortlist, you need to make a judgement call. We also know that it’s very difficult to ever really know if you have maximised value for money – after all, nobody likes to miss out. Even though VFM is not an exact science, this does not mean that trying to evaluate VFM is pointless.

A VFM assessment is an important exercise, particularly for big financial decisions. To do this, you need a framework for making a decision that helps you to evaluate the importance of features and benefits, and how much you are prepared to pay for them.

THINGS TO CONSIDER

When it comes to saving for retirement, VFM is deceptively simple – invest in order to maximise after-fee outcomes, which include financial and non-financial returns. However, the devil is, as always, in the detail:

- The players: There is a range of different roles within the retirement industry. These include fund sponsors, trustees, lawyers, auditors, administrators, consultants, investment managers, regulators and so on. Each of these provide and charge for their respective services, and together they form the retirement value chain.

- No crystal ball: When you buy a smartphone, you know what you will get – push X (or ask Siri/ Alexa/Google to do it for you) and Y will happen. However, when it comes to investing, the future is inherently unpredictable, and it is impossible to make a decision that will, with absolute certainty, maximise your future after-fee outcomes.

- Fees are easier to understand: The difficulty with measuring VFM means that many commentators tend to look to past returns and narrow in on costs because this is the most predictable and measurable component of VFM. While we fully agree that inappropriately high costs can have a detrimental impact on retirement outcomes, we feel that the simple focus on fees alone does not provide a meaningful and accurate assessment of VFM.

- Price check? A big challenge in assessing VFM is comparability across offerings given the different ways in which providers charge for their services. The industry has put in place measures to help improve transparency and comparability – more on this below.

VFM AND RETIREMENT SAVINGS

So how do you assess VFM when it comes to retirement fund matters? First, you need clear objectives or goals against which to measure outcomes. What are you trying to achieve, and how will you assess success? This is not about investment performance alone, but rather about requirements across the full value chain. This helps you to set out your requirements, considering:

- The range and quality of services that you need to assess the options available to you in the market.

- The costs of each component, including how and why they might change over time.

- Access to the skills and experience to evaluate and understand your options, for example, by employing the services of professional trustees and consultants.

There are few topics more emotive than costs. Costs are after all, a mathematical certainty – for any given return, the lower the cost, the better the outcome. Therefore, funds should be aiming for the lowest possible costs for their clients, right?

The reality is that it’s a lot more complex than that. First, returns are not a certainty and vary significantly by approach. While attention to the appropriateness of costs are critically important, a focus on costs at the exclusion of everything else will lead to unintended consequences.

When it comes to costs, the questions that we should be trying to answer are whether fees are commensurate with the service provided, and whether they create the right incentives by aligning the long-term interests of retirement fund members and service providers.

INCREASING TRANSPARENCY

Costs disclosure has improved in recent years. In the unit trust market, this started with the introduction of Total Expense Ratios (TERs) in 2007 and, more recently in 2017, Effective Annual Charge (EAC) disclosures. In the institutional retirement industry, the Association for Savings and Investment in South Africa’s (ASISA) Retirement Savings Cost (RSC) Disclosure Standard came into effect in 2019 and is designed to help employers make better cost comparisons between different umbrella funds. RSC separates out the cost components, including the costs of advice, administration, investment management and ‘other’ costs.

This should, in turn, help to separately assess the VFM of each component. ASISA has also released a standard for the disclosure of EACs to members of retirement funds, which will become effective in 2020. The Default Pension Regulations, which became effective in March 2019, require comprehensive disclosure on the costs of default investments and should further improve cost transparency, and hence allow for better assessment of value.

INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT COSTS

Investment costs are a significant contributor to the overall costs of running a retirement fund. Investment fees have come down over time, helped by increased competition and the consolidation of smaller funds into umbrella funds.

Consultants have also played an important role in driving competition within the investment industry by assisting their clients with selecting and monitoring managers and negotiating commercial terms.

Larger retirement funds generally benefit from economies of scale and stronger bargaining power. According to the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA), the number of South African retirement funds has reduced from 13 000 to just under 1 500 over the past 10 years. Going forward, the regulator would like to see further consolidation to simplify the regulatory regime and further improve economies.

Appropriately structured performance-based fees have been a prevalent feature of many of the larger retirement funds in South Africa for many years. This has ensured that the fees charged for active management are directly linked to performance delivered. Performance fee methodologies have evolved over time to ensure alignment, appropriateness, transparency and ease of understanding.

In addition, investment costs should always be seen in the context of the portfolio strategy. For example, some retirement funds invest in more expensive alternative asset classes (e.g. infrastructure), while high-equity portfolios are typically more expensive than low-equity portfolios. Fees also vary across different investment strategies – most notably whether a strategy is actively managed or tracks an index.

COST OF RUNNING A RETIREMENT FUND

So how much does it cost to run a retirement fund? While RSC data are not yet widely available, funds do produce financial statements. The Registrar of Pension Funds’ Annual Report for 2017 provides a consolidated view of the retirement fund industry. Regulated funds had total assets under management (AUM) of approximately R2.4 trillion, with total ‘expenses incurred in managing investments’ of R7.4 billion (0.3% of AUM) and total administration (and other) expenses of R9.5 billion (0.4% of AUM).

The investment fee of 0.3% appears low and it is worth considering why. It is likely that the larger funds with the bulk of the AUM bring down the average. Similarly, some funds manage their investments inhouse or use lower-cost passive strategies.

There is also often a high use of performance-based fees on their active mandates. Active management has struggled over the past five years, and it is likely that the lower fees paid by many retirement funds reflect the fact that their active managers have tended to underperform their benchmarks in recent times.

Furthermore, some of the fees incurred in pooled vehicles may not be included in these numbers. However, even if you adjust for this, it is reasonable to conclude that investment fees are probably lower than many would expect. Naturally there are funds that do pay inappropriately high fees on behalf of their members, and one of the FSCA’s current goals is to identify those funds and ensure ameliorative action is taken.

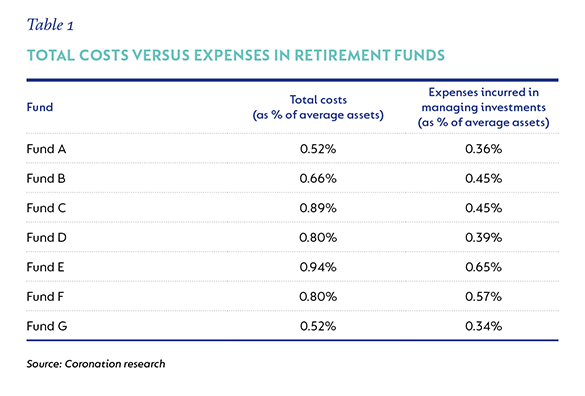

If we dig a bit deeper, we find that most large retirement funds publish their own annual statements on their websites. Table 1 shows the fees incurred by a sample of large funds (with total assets greater than R20 billion) using each of their most recent published annual reports.

Based on the sample data, investment costs varied between about 0.35% to 0.65%, and total costs (investment plus administration) varied between 0.5% to just under 1%.

VALUE CREATION

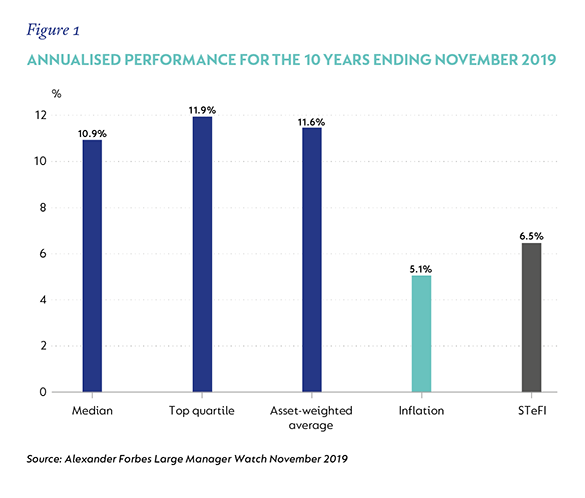

While value is created (and should be assessed) across all parts of the value chain, for simplicity we focus on investment performance. Figure 1 shows the performance of the Alexander Forbes Large Manager Watch over the past 10 years. This reflects the actual historic performance of the largest multi-asset class funds in South Africa used by retirement funds and is a reasonable representation of industry performance.

It is notable that the asset-weighted average is 0.7% per annum higher than the median manager, equating to 7.2% cumulatively over that 10-year period. What this suggests is that retirement funds have generally allocated well over time, because the bulk of the money has been invested with the better-performing managers. We see similar results when looking at a broader universe of investment managers in the survey. It also puts the range of investment costs (see Table 1) into perspective; the range of fees paid is relatively small in comparison to the potential performance impact of a fund’s asset allocation and manager line-up, showing that it has been worth paying slightly higher fees for better returns.

ACTIVE MANAGEMENT VERSUS INDEXATION

No discussion on VFM is complete without looking at the difference between active and passive investing. While this is hugely topical worldwide, it is a debate we don’t ventilate often because we are unashamedly active in our approach, but also agree that there is a place for index-based investing. We prefer to explain what it is that we do and how we go about it and show the value that we have delivered for our clients over the long term. The allocation decision then naturally sits with the asset owner, where it belongs.

The pros and cons of each approach are generally well understood and do not need to be reproduced here. From a VFM perspective, the key point to reiterate is that the future is unknown, and no investment strategy can guarantee that it will outperform another. Investment markets perform in cycles and these cycles often last for long periods.

For example, index trackers have performed well (globally) since the end of the Global Financial Crisis in 2009. But cycles do eventually turn, even though it is impossible to know exactly when this will happen. Therefore, a VFM exercise that focuses on recent past performance may lead to sub-optimal decisions. A more effective approach to VFM may be to consider which strategies are appropriate for which markets, considering market efficiency, performance expectations and costs.

A blend of high-quality investment managers with sound philosophies, strong processes and skilled teams should, on a balance of probabilities, deliver good value to members over the long term. These blends may (or may not) include allocations to index strategies – based on the judgment of the asset allocator having regard for VFM, diversification and other factors. It is also worth noting from the section on fees above that the fee gap between active and index-based investing does not appear to be as high as traditionally thought, particularly where good performance fee structures are in place.

STEWARDSHIP AND ESG

The importance of retirement funds and their investment managers acting as responsible stewards of investor capital has grown rapidly over the past decade. In 2019 this kicked into high gear, with investors and regulators demanding even greater action to ensure that investments are made responsibly in order to ensure long-term sustainability.

Promulgated in 2011, regulation 28 (2)(b) of the Pension Funds Act requires trustees to consider environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors when setting out fund mandates; in 2019, the FSCA released a guidance note that sets out its expectations for how funds should go about meeting these obligations. This includes the requirement for funds to apply active ownership practices to encourage investee companies to behave in a sustainable manner.

Stewardship and engagement are beneficial because they enhance shareholder value and support investors in the execution of their fiduciary duty. This responsibility is usually delegated to investment managers, and funds therefore need to be satisfied that the managers that they appoint have robust ESG practices and can act as responsible stewards of their capital. This is another important VFM consideration. When evaluating an investment manager, funds should not only consider the traditional factors, such as performance, risk management and service, but also whether the manager will enable the fund to meet its sustainability obligations.

Active ownership is most effective when managers have informed dialogue with investee companies to influence meaningful long-term outcomes. It is therefore difficult to decouple company analysis from active ownership because of the need to understand the activities of the companies with which you engage.

ARRIVING AT GOOD VALUE

How do we bring all of this together? First, we need to be clear about the conditions required for ensuring good VFM:

- Be clear about the outcome you require and the services that you need to achieve this outcome. Focus on the total benefit and costs across the full value chain.

- For investments, understand that future returns are unknown and VFM decisions require informed judgement. Ensure that all aspects of investment management are covered, including the need for effective ESG practices.

- Understand your costs and make sure that they are competitive and commensurate with the quality and scope of services provided, and create the right incentives for good member outcomes.

- Avoid conflicts of interest wherever they may create conditions that work against member best interests.

Ultimately, member interests (and hence VFM) are best served by a competitive, transparent and well-regulated market with low barriers to entry. While there is always room for improvement, the industry does by and large meet these criteria. Professional consultants foster competition and transparency between providers, and fee disclosures and comparability are improving.

Fund consolidation should improve efficiency – with the caveat that large funds should carefully manage any conflicts between the interests of sponsors and members.

At an industry level, if we want to significantly improve VFM, the bigger issues need to be addressed, such as ensuring that more people contribute higher amounts to retirement funds, preservation rates improve, and better decisions are made at retirement. The Default Regulations attempt to address many of these issues. Most members gravitate to defaults, which should reduce complexity and increase the focus on ensuring that defaults provide good VFM to members. However, the effectiveness of the Default Regulations will only become evident in time.

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional