Stuck in the mud

01 May 2013 - Chantal Valentine

There’s a nasty little feedback loop in South Africa at the moment: The wide current account deficit (partly due to local factors and partly due to external ones) is keeping the rand weak, which is fostering inflation; while domestic growth seems to be struggling, which is also partly reflective of lower export demand hitting the manufacturing sector. The mining strikes have also negatively impacted both exports (contributing to poor trade data and dampening growth) and rand sentiment. And to the extent that strikes win higher wage settlements, they too contribute to inflation rising. Policymakers are in a cul de sac – both fiscal and monetary policy are already at the loose ends of the spectrum, and the latter in particular is being constrained by inflation. South Africa is in a situation of relatively low growth and inflation at the top end of the target range, with growth risks still to the downside and inflation risks to the upside – the ‘stagflation lite’ scenario is materialising.

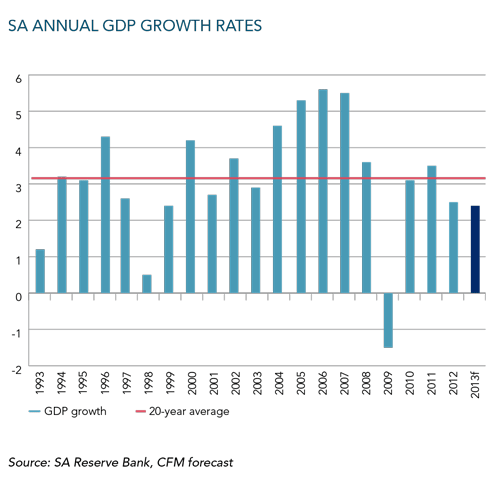

With the 4.5% – 5.5% growth rates of the mid-2000s looking increasingly out of reach, reality is setting in that those boom time growth rates did not mean a new, higher level of potential for growth for South Africa. Instead, it is looking like the ‘old normal’ potential growth estimates of 3% – 3.5% are back; this is the range that the country has mostly been in for the past five years (dipping below in the post-financial crisis recession) and where it is expected to remain in the next few years. The following chart shows clearly that the mid-2000s growth rates look more like an aberration than the start of a new trend.

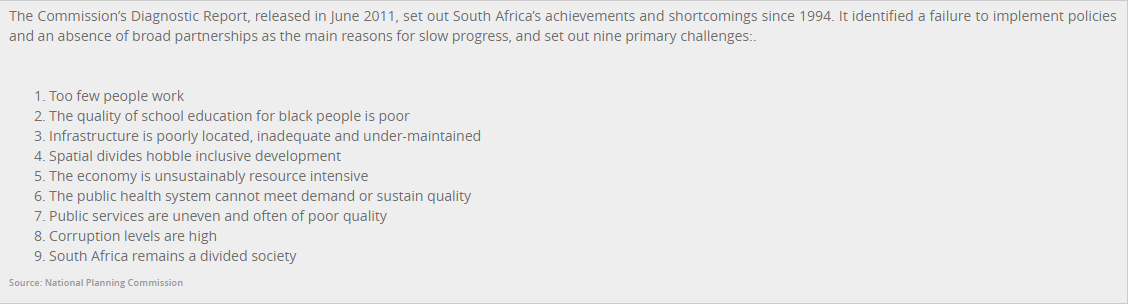

This is, of course, not growth ‘stagnation’ in the true sense, but it is a disappointing and lacklustre growth rate. The cause of this is not too-tight policy but structural impediments. The challenges have been well identified in the National Development Plan, and it is hoped that government can embark on policies to address these.

The Commission’s Diagnostic Report, released in June 2011, set out South Africa’s achievements and shortcomings since 1994. It identified a failure to implement policies and an absence of broad partnerships as the main reasons for slow progress, and set out nine primary challenges:.

Despite growth being lacklustre, South Africa has experienced a significant widening in its current account deficit over the past year; it is now at levels more usually associated with much stronger domestic growth rates. There are a number of factors behind the wider deficit, and these same factors mean it is unlikely that the deficit will narrow very significantly in the shorter term. Export performance has been pedestrian due to a combination of weak growth in many export destinations and domestic production disruptions due to strikes. Imports, while showing slower growth rates over the course of 2012, are still growing faster than exports on a combination of infrastructure-related and consumer goods imports, with consumer spending having been quite resilient last year against a background of easy monetary policy, high wage settlements and contained inflation. While import growth is expected to slow this year as the consumer faces more pressure (including more expensive imports from a weaker rand), and exports may make up some ground from last year’s strikes, the underlying deficit is expected to remain wide as export demand remains lacklustre, and infrastructure imports remain robust. Added to these, the services and income account will probably remain close to its trend deficit of around 3% of GDP, while transfers are expected to exceed 1% of GDP this year. Therefore, while the deficit is expected to narrow over the course of the year, it is expected to remain relatively wide.

The still-wide current account deficit means that the rand remains vulnerable. In rand terms, we estimate a deficit of over R200 billion this year. This, in turn, implies that South Africa needs capital inflows averaging around R18 billion a month in order to prevent the rand from depreciating. Although the country managed just over R200 billion of capital inflows last year, this was a surge from the previous year on the back of the large inflows due to South Africa’s inclusion in the Citigroup World Government Bond Index (usually estimated at around R50 billion – R60 billion). It is unlikely that this will be repeated. Prospects for any large increase in foreign direct investment also appear slim given the current socio-political backdrop, especially given unresolved labour issues. Equity inflows could also be affected by similar sentiment. While both bond and equity inflows will to a large part also depend on global flows to emerging markets, South Africa-specific factors could see an underperformance relative to the average inflow. All in all, we do not think capital flows would match our expected current account deficit this year, which implies that the rand will remain quite weak. While the search for yield (especially following the new Bank of Japan policy) could give the currency some near-term support, bear in mind that, even despite the favourable yield-seeking global environment, the rand has depreciated significantly from better than R/$ 7 in late 2010/early 2011; global risk appetite alone is not enough to offset unfavourable fundamentals.

In turn, rand weakness has been a factor pushing inflation higher again. The previous high inflation cycle could in large part be attributed to ‘exogenous’ factors of food, energy and administered prices (especially electricity). This time around, the story is not so simple. The rise in inflation has happened despite moderation in food, energy and electricity prices – all of these are recording significantly lower inflation rates than a year ago. In February, food inflation was 4% lower than February 2012; electricity inflation was 7% lower, and petrol inflation was nearly 10% lower. These popular culprits are clearly not the problem at the moment.

Rather, two other themes are becoming more evident: (1) rand passthrough is pushing prices up, not dramatically in most cases, but across a broad range of categories; and (2) services sector inflation, which had generally been quite well contained, is now pushing above target in a number of categories. We would ascribe the latter at least partly to second-round effects from wages, electricity, etc. The bottom line is that inflation pressures have shifted from being ‘exogenous’ to being felt in areas that are determined in the private sector. This is also reflected in core inflation rising. We have long expected CPI to breach the target range this year, and at the time of writing it was on the cusp of doing that, having reached 5.9% in March. We think CPI will spend much of the next year above the target range, although recent sharp falls in the oil price mean this breach will probably be shallower than previously expected.

This leaves the central bank even deeper in the same quandary – faced with sluggish growth but with continued upside risks to inflation. An interest rate move cannot be ruled out; a cut in the case of serious growth concerns and a rise in the case of serious inflation concerns, but the hurdles for both are probably quite high, and the most likely outcome is unchanged rates for a long time. However, we continue to believe that the next move following this extended period of loose policy is likely to be higher, albeit probably a long way off from now.

CHANTAL VALENTINE joined Coronation as economic and fixed interest strategist in 2003. With more than 20 years’ experience in analysing local and global markets, she plays a critical role in the investment decision-making process.

If you require any further information, please contact:

Louise Pelser

T: +27 21 680 2216

M: +27 76 282 3995

E: lpelser@coronation.co.za

Notes to the editor:

Coronation Fund Managers Limited is one of southern Africa’s most successful third-party fund management companies. As a pure fund management business it provides individual and institutional investors with expertise across Developed Markets, Emerging Markets and Africa. Clients include some of the largest retirement funds, medical schemes and multi-manager companies in South Africa, many of the major banking and insurance groups, selected investment advisory businesses, prominent independent financial advisors, high-net worth individuals and direct unit trust accounts. We are 29% staff-owned, have offices in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Durban, Gaborone, Windhoek, London and Dublin and are listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. As at the March 2013 quarter-end, assets under management total R409 billion.

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional