The active versus passive debate

01 May 2013 - Kirshni Totaram

The debate between active and passive investing has once again taken centre stage in much of the financial press. While the take-up of passive investing in South Africa is still relatively low, it is curious to see that the majority of the data presented is in favour of passive, with very little being said in support of active investing. Both investment approaches have merit and need not be mutually exclusive.

In this article we share our view that, with the right active manager, significant value is added to investor portfolios over time. Our intention is not to deliver another technical paper or build on what has already been published, but rather to provide our perspective garnered over a 20-year history of producing market-beating returns.

The current market environment

Globally, we are operating in a low-return environment where real returns are becoming increasingly difficult to achieve. Correct asset allocation and stock selection will become even more critical, and the profile of investor portfolios may in future differ materially from the past. With the likelihood of achieving future real returns in the region of as low as 5% – 6%, alpha becomes an essential building block to achieving long-term retirement targets.

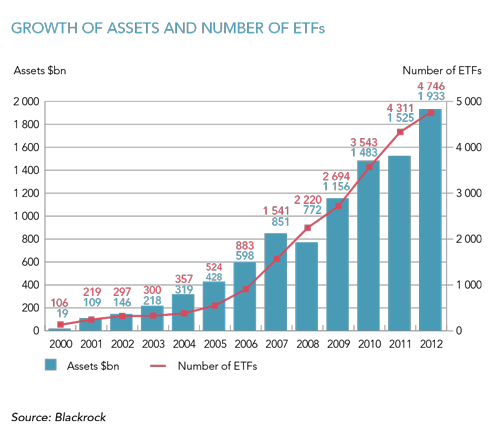

It is against this backdrop that the debate between active and passive is once again on the agenda. Positioned as producing better performance net of (lower) fees, investors around the world are pouring into passive investments. In the last three years, flows into exchange traded funds (ETFs) have exploded as seen in the adjacent chart.

Active in context

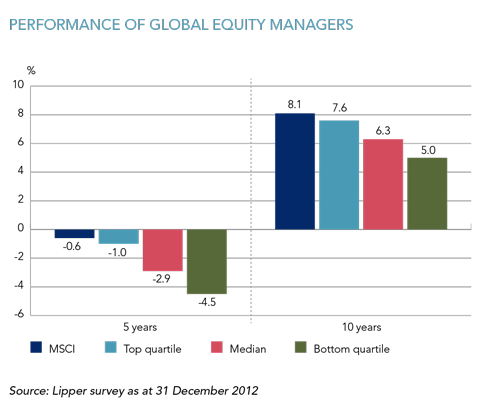

The criticism levelled against active managers is their inability to outperform the markets net of fees. And the headlines support this. Take for example the Lipper survey of contributing global equity managers: over the 5- and 10-year periods to end December 2012 the top quartile, median and bottom quartile of managers have all underperformed the MSCI World Index; with only 20% of managers having produced an outperformance.

This is the type of information that proponents of passive investing repeatedly quote. But we don’t believe that it tells the full and complete story. Not all active managers are equal, and nor are they all truly active. The numbers above are clouded by the inclusion of the broad spectrum of managers deemed to be active or, in other words, every manager that is essentially not passive.

In the survey data are a large number of closet index huggers that skew the data to underperformance, particularly on an after-fee basis. The reality is that active management is not homogenous. In our view, the true definition of active management is the use of fundamental research and independent investment judgement to assess the value of assets, and the creation of a portfolio that will outperform a benchmark over a specified (long) time period. Active portfolios are typically more concentrated than an index (fewer stocks), and position sizes vary greatly relative to the weightings in an index. This is portrayed as the active share. An index hugger, on the other hand, will have a portfolio that is only slightly tilted from the index, indicated by the (greater) number of shares, small deviation in position sizes relative to the benchmark and volume of turnover. The time period over which truly active managers are assessed is also important. Ideally one should look at returns over 10 years, but no less than five years, to ensure that luck and market conditions are eliminated.

Applying this theory closer to home, we looked at the South African unit trust and institutional markets over the last 20 years. Over this period, the JSE All Share Index (ALSI) returned an annualised 16.6%, while the average actively managed general equity unit trust fund produced an annualised 17.3% (after fees). Further, the median of the Alexander Forbes South African Large Manager Watch™ Survey has delivered returns of 17.1% p.a. – a staggering 10.6% above inflation on an annualised basis. What also becomes incredibly compelling is that the managers who have generated the top quartile of returns have shown a significant persistency in generating those returns over the past two decades.

Differing market cycles

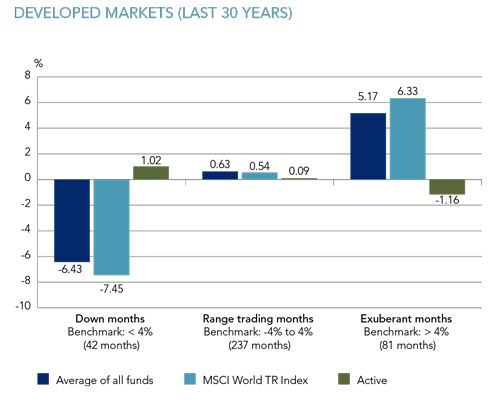

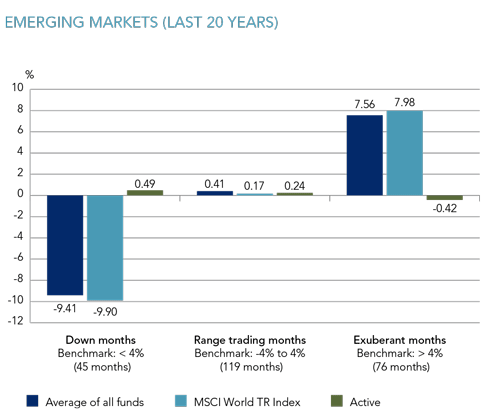

One should also be wary of data that only shows the performance and behaviour of funds at certain snapshots in time; active managers react differently in different market conditions. Using 30 years of developed market data and trying to strip out the closet index huggers (through the survivorship bias) we were able to uncover some extremely interesting information. Active managers add the greatest value in low-return environments (as shown in the following chart), outperforming the index in both down months and range trading periods. The only time that truly active managers are left behind is in raging bull markets, which we believe makes intuitive sense. But the important point is that they are able to protect more capital during down-market periods – a low return environment – which creates a much more stable base and a better tailwind to compound returns when markets recover. The asymmetry of investor behaviour confirms this wholly sound proposition that, when markets are up 20%, investors are content with a return of 18.5%, rather than be faced with a scenario that produces a return of -15% when markets are down 10%. So, in effect, good active managers are able to deliver outperformance in market environments that matter most to the investor.

Over the last 30 years, the top quartile of active managers in developed markets returned an annualised 24.8% (after fees), while the MSCI World Index returned 10.1%. This is an annualised alpha of 14.7%. Likewise, the top quartile of active managers in emerging markets produced an annualised 21% over the past 20 years, compared to the 6.3% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index – resulting in an annualised alpha of 14.7%. This data crushes the myth that good active management does not add value.

Taking a closer look at passive investing

Passive investing can be a great low-cost way to gain market exposure, particularly in more efficient markets. Furthermore, as stated in the opening paragraph, the use of passive and active investing need not be mutually exclusive. For many investors who feel that they are unable to identify skilled active managers in certain areas, passive may be the most viable solution. But the decision to go passive should not be based purely on a dislike for active. It should be a decision based on the relative merits of passive, with a complete understanding of the associated risks.

When most people think of passive investing, they see it as a simple allocation to an index that is safer (less risky) and cheaper (lower fees) than active investing. Below we take a closer look at each of these factors.

Firstly, we believe that costs should never be considered in isolation. The compounding of returns over the long term can result in material gains and thus investors should always look at investment returns less costs.

Secondly, let’s define risk. In passive investing the definition of risk is firmly defined as tracking error (deviation from the benchmark index) and the perceived elimination of benchmark risk and manager selection risk. It does not cover other risks such as maximum drawdowns, permanent loss of capital, etc., which we believe are ultimately more important to the investor.

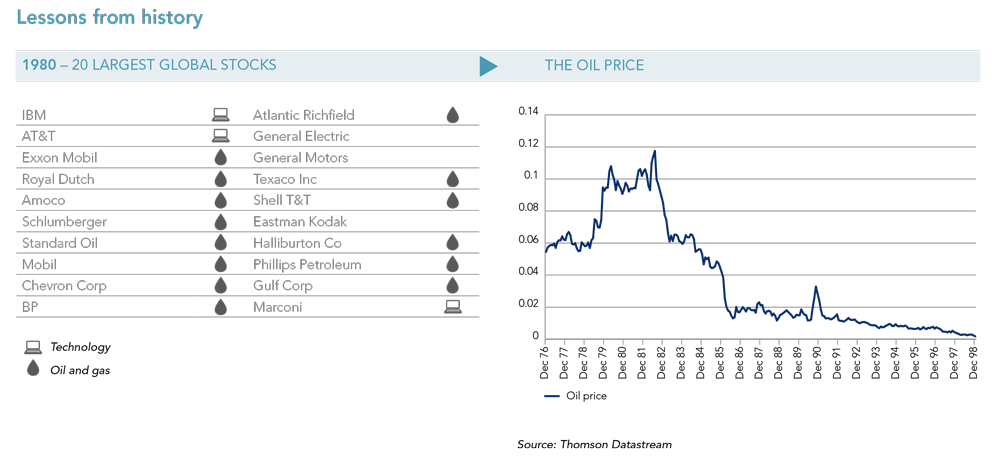

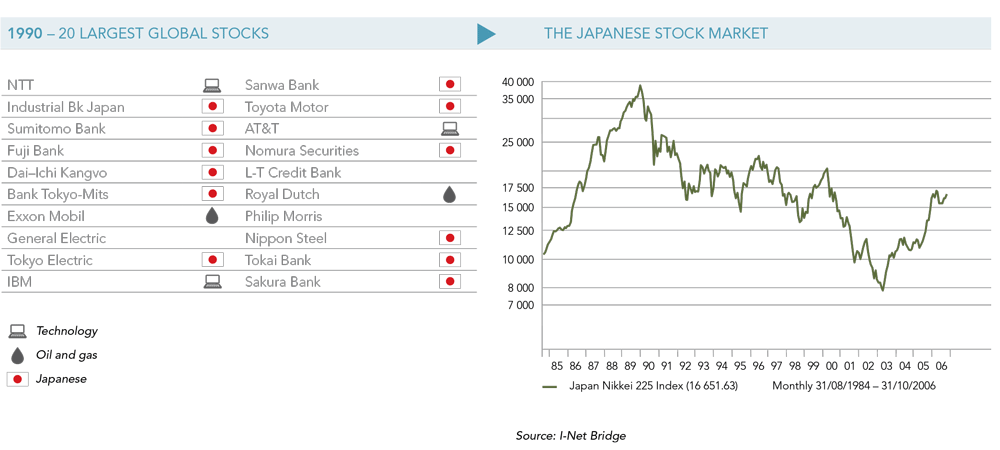

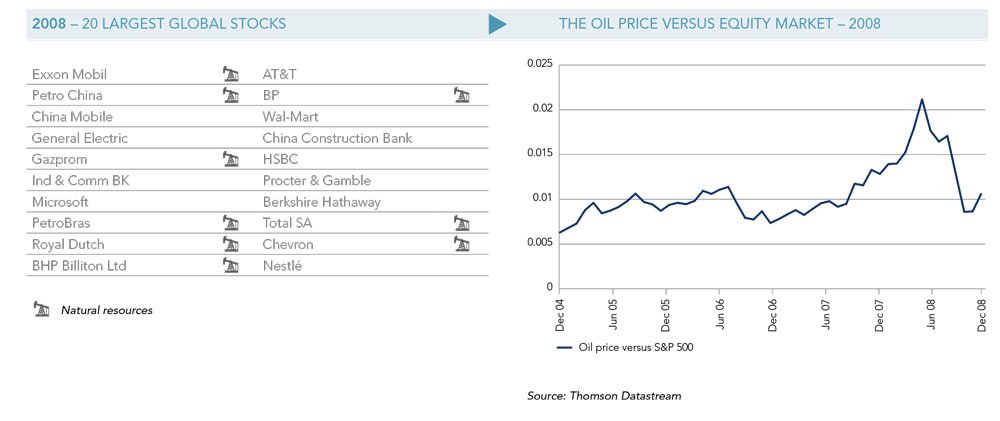

Thirdly, the decision to go passive is in itself an active one. The investor has to choose the right benchmark index from an array of materially different indices, each offering diverse market, sector and stock exposure. It is also important to note that many indices are not always reflective of the investor’s potential investible universe. Take for example the MSCI Emerging Market Index. This is an index made up of more than 1 000 shares that represent the leading emerging markets, yet only 30 listed shares on the JSE represent the whole of South Africa in this index. In addition, by virtue of mimicking the index the investor will always be buying assets that are going up, and hence potentially overpriced, and selling assets that are underpriced – the antithesis of active management. History tells this story extremely well in terms of how much value investors have lost as a result of blindly investing in just the biggest stocks in the index. Overleaf we look at the 20 largest global stocks in 1980, which look very different to those of a decade later and the decade after that. History may not often repeat, but it does rhyme a lot (Mark Twain).

Everything about an index is based on historical data and trends. Indices do not consider forward-looking intelligence and therefore cannot take account of what we, as investors, believe securities will deliver in the future. This is especially pronounced in rapidly changing environments where history may not be the best indication of the future. Take, for example, the classic case of emerging markets, where one just needs to look at the impact of mobile telephony, formalised banking and formalised retail to see the change in shape of many countries’ economies. Emerging market environments are changing at such a rate that there is very little resemblance between the past and the future.

Even for developed markets, while passive investing may have been very viable in the past, the jury is still out as to the relevance that this type of investing will have going forward, given the unprecedented level of macro volatility and uncertainty that we currently see.

Caveat emptor

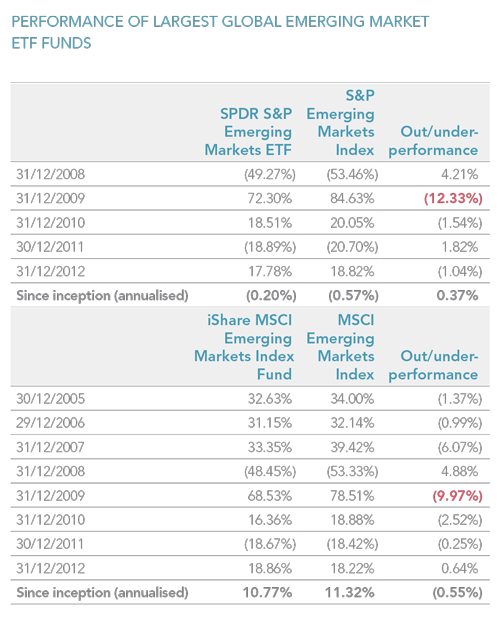

When making a passive investment, pay careful attention to what you are buying. You cannot buy the index. Your investment will be into an index fund. Given that the majority of flows have gone into emerging markets ($55 billion in 2012 alone), we took the two largest emerging market ETFs, and compared the returns with those of the respective indices.

The results were surprising. For investors in these funds, it has been a highly volatile (not just in absolute returns but also the relative returns) experience, and most certainly not their expected index return less fees. The outcome has also been further exacerbated by the fact that an investor’s ultimate return and outcome is HIGHLY dependent on the start date of investment – a risk which index investing is meant to eliminate. For example, if you had invested in the SPDR S&P at the end of 2008, you would have been materially behind the index, -12.33%, and under-performed on a cumulative return basis. An investment in the iShare fund would have delivered a similarly disappointing experience.

In conclusion, we are unequivocally active managers and believe in the value that we add to client portfolios over the long term. When investing with an active manager, understand their philosophy and process, and when assessing performance don’t just look at a snapshot in time but at the full long-term picture. There is a place for passive investing, but understand that it comes with its own set of risks. Every decision you make regarding your choice of investment vehicle is an active one – never forget that. Each investor needs to weigh up his or her own assessment of risk versus the available investment options, and determine which (active or passive mandate) offers the best risk-adjusted return after all fees.

KIRSHNI TOTARAM heads up the institutional business and is a member of the executive committee. She is a qualified actuary and a former manager of the Coronation Property Equity Fund.

If you require any further information, please contact:

Louise Pelser

T: +27 21 680 2216

M: +27 76 282 3995

E: lpelser@coronation.co.za

Notes to the editor:

Coronation Fund Managers Limited is one of southern Africa’s most successful third-party fund management companies. As a pure fund management business it provides individual and institutional investors with expertise across Developed Markets, Emerging Markets and Africa. Clients include some of the largest retirement funds, medical schemes and multi-manager companies in South Africa, many of the major banking and insurance groups, selected investment advisory businesses, prominent independent financial advisors, high-net worth individuals and direct unit trust accounts. We are 29% staff-owned, have offices in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Durban, Gaborone, Windhoek, London and Dublin and are listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. As at the March 2013 quarter-end, assets under management total R409 billion.

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional