Quarterly Publication - July 2017

NOTES FROM MY INBOX - July 2017

It is scary how quickly we have reached the halfway mark to this year, which has so far been filled with much newsflow and surprises. The UK electorate delivered another shock result at the start of the crucial Brexit negotiations, the US president’s intemperate tweets are slowly shaping a new global diplomatic order and tensions are escalating in the Middle East. Global markets have been moving higher in fits and starts, but a recent sharp sell-off in global bonds, a continuous European banking crisis and a slump in the oil prices have unnerved many.

As a South African company, we have a high uncertainty threshold. There is no doubt that this threshold has been severely tested during the first six months of the year as the political climate in South Africa has deteriorated further. We have been managing money in an open emerging market for almost a quarter of a century, investing and protecting clients’ savings amid ongoing currency and political shocks. This has stood us in good stead, helping us become disciplined investors who can cut through the noise and focus on the long term. It has also helped us to find value where others may only see risk, especially in emerging markets, where we understand the dynamics of formalising economies despite political turmoil.

Our experience in emerging markets has also granted us a firm understanding of the limitations of passive investing – a trend that has gained massive flows in global markets in the last few years. These shortcomings were highlighted recently after the MSCI decided to include selected China A-shares in its emerging markets’ benchmark index for the first time. After extensive consultation, it decided on 222 shares (out of more than 3 000) considered suitable for the index. The decision sparked concern among passive investors who have to track the index. The Chinese market is opaque, with questions about ownership structures, shadow finance and the true extent of state involvement in each company. In addition, the selected companies are skewed towards the problematic Chinese financial sector. Above all, as a number of commentators pointed out, it demonstrated that tracking an index is not a passive investment decision at all.

“It is a neat reminder that the style of investing they (passive investors) think they have embraced does not actually exist,” as the editor of MoneyWeek, Merryn Somerset Webb, wrote in the Financial Times. “There is no such thing as passive. Someone has to decide what is an emerging market, someone has to decide which emerging markets are the most important and someone then has to decide which stocks define each emerging market.” In fact, what this style of investing does is outsource the investment decision to the index providers themselves.

No matter how artfully the passive sales pitch is presented, all passive investments fundamentally require investors to make an active decision. Investors need to choose from the myriads of indices, many with increasingly complex rules and algorithms, each with a potential materially different outcome over long periods.

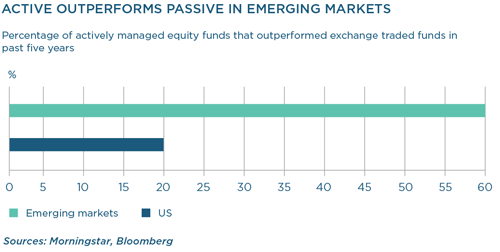

In addition, we have long argued that passive investing is particularly ineffective in emerging and frontier markets. Indices for these markets do not offer investors a true reflection of the investable potential and economic drivers of these markets, nor the best companies that investors could invest in (at the right price). The benchmark indices in these markets favour shares that are liquid and are usually skewed towards lower-quality companies, which have larger weightings due to their free floats. Typically, these indices have a lot of exposure to the financial sector and other highly regulated industries – and not to companies which can benefit most from fast-growing structural changes in developing markets. Often, these include businesses with large foreign parents (like Heineken, Diageo and Unilever) which have great growth prospects but a lower free float, and therefore smaller weightings in the indices.

Tracking the index can also be hazardous in some highly concentrated markets like South Africa. While investors tracking the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 will end up with a portfolio where the top 10 largest stocks represent less than a fifth of their portfolio, in a concentrated market like South Africa, Naspers will represent almost 20% of your portfolio (if you are tracking the Shareholder Weighted Indices [SWIX]). One of the biggest selling points of passive investing is that you remove stock-specific risk and simply get the return of the market. In emerging markets, often investors end up with much more single-stock risk, and they do so without a skilled and experienced investment professional held accountable for the appropriateness of that weighting.

At Coronation, we construct clean-slate portfolios of our highest conviction views. We believe that this approach affords us the ability to outperform indices over meaningful periods of time.

IN THIS EDITION

We are extremely concerned about the recent events in South Africa. Simon Freemantle explains the political forces behind the current turmoil on, a sobering read.

The respected emerging market analyst Jonathan Anderson has contributed an exclusive article on China’s prospects. While for the foreseeable future the country should remain stable, Jon warns that investors need to be aware of risks in the Chinese economy. China may not escape its debt boom without pain.

In addition to our quarterly contributions on the markets, you will find a number of investment cases in this edition, including for the US fashion retailer L Brands, mobile money operators in Bangladesh and Kenya and the South African hospital group Mediclinic.

We hope you enjoy the read as we prepare for the next half of this eventful year.

United States - Institutional

United States - Institutional