Investment views

Winning businesses: an agile take on the traditional “Quality” approach

- questioning a static definition of quality when disruption is the only constant

The Quick Take

- Traditional methods of assessing quality remain important, but additional considerations are necessary in today’s dynamic world

- Technological and societal changes are challenging many traditionally strong business models. Against this evolving backdrop, a static definition of quality is dangerous

- We focus our attention on identifying “winning businesses”. These businesses are agile, innovative and on the right side of technological change

“Quality” is an investing style that is widely referred to in the asset management industry. It has also proved to be an effective marketing slogan – perhaps this is because “buying quality” would seem to be self-evident. After all, who would openly admit to preferring the alternative? The term is also aspirational, evoking a feel-good factor that makes it an easy choice for clients.

However, it is a term that is seldom fully explained or quantified, leaving it open to interpretation. It is also often backwards looking, relying on metrics that a company has delivered in the past. In a world of disruption driven by accelerating technological change, we choose rather to focus our attention on “winning businesses” – that is, companies that are fit for purpose in the modern world. This article elaborates on our thinking.

A TRADITIONAL ASSESSMENT OF QUALITY

So, what makes a company high quality or low quality? A traditional assessment would consider factors including the strength and heritage of its brands, its products’ pricing power and the industry barriers to entry. These inputs ultimately allow the business to earn a certain return on invested capital (ROIC), which is the key consideration behind a traditional quality assessment. The ability of a business to compound earnings at high returns on capital rightly is, and will always be, one of the key determinants of quality. Other important factors to consider include its ability to convert earnings into cash flows, the predictability of its earnings or range of outcomes, and the quality of its management team. Many of these inputs are, however, backward looking and don’t necessarily tell us all we need to know about what will happen in the future.

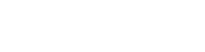

Looking back at history, companies that tick these boxes have understandably received a lot of interest from investors. Many are household names with strong brands, and their products are often defensive, with ongoing demand irrespective of macroeconomic conditions. Examples would include Unilever and Reckitt Benckiser in the household and personal goods category, Nestlé in packaged foods, Estee Lauder in skincare, Diageo in the alcohol category, Roche in pharma or Disney in media. One can expand this net to include historically faster growing names that are more economically sensitive; some examples would be Nike in sports apparel, Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy (LVMH) in luxury goods, or Adobe in software. These businesses all boast very healthy returns on invested capital, in some cases well north of the 20% mark.

This all sounds great on paper, yet these names have all performed very poorly versus the MSCI All Country World Index (MSCI ACWI) benchmark over the last five years, with some being down heavily in absolute terms (Figure 1). The same is true over longer time periods; over 10 years, only two of these names (LVMH and Adobe) have outperformed the market. There are various reasons for this – disruption, a lack of innovation, or simply a starting valuation that was too rich. Companies like Nestlé and Unilever have simply struggled to grow, generating minimal organic revenue growth of around 1% per annum over the last decade when measured in US dollars, which is well below inflation. It is thus clear that being classified as quality does not in itself guarantee a positive investment outcome.

NOT ENOUGH IN A WORLD OF DISRUPTION

The reality is that we live in a rapidly changing and dynamic world. Technological changes have disrupted many previously great business models, while societal changes have altered our habits. Aspects of our daily lives, including shopping and media consumption, continue to shift online, while social media has dramatically lowered the barriers for new brands to launch. Business models and advertising strategies have thus had to change against a backdrop of increased brand fragmentation. This makes it more difficult for traditional brands to stay relevant in a more competitive online world. Consumer preferences and habits have also changed, with an increased focus on health and wellness. Younger people are drinking less and prioritising travel and experiences over spending on goods, while the rise of GLP1s[1] and other weight-loss drugs has the potential to change our eating habits. The convenience economy is growing strongly off a low base, with significant potential consequences for traditional retailers.

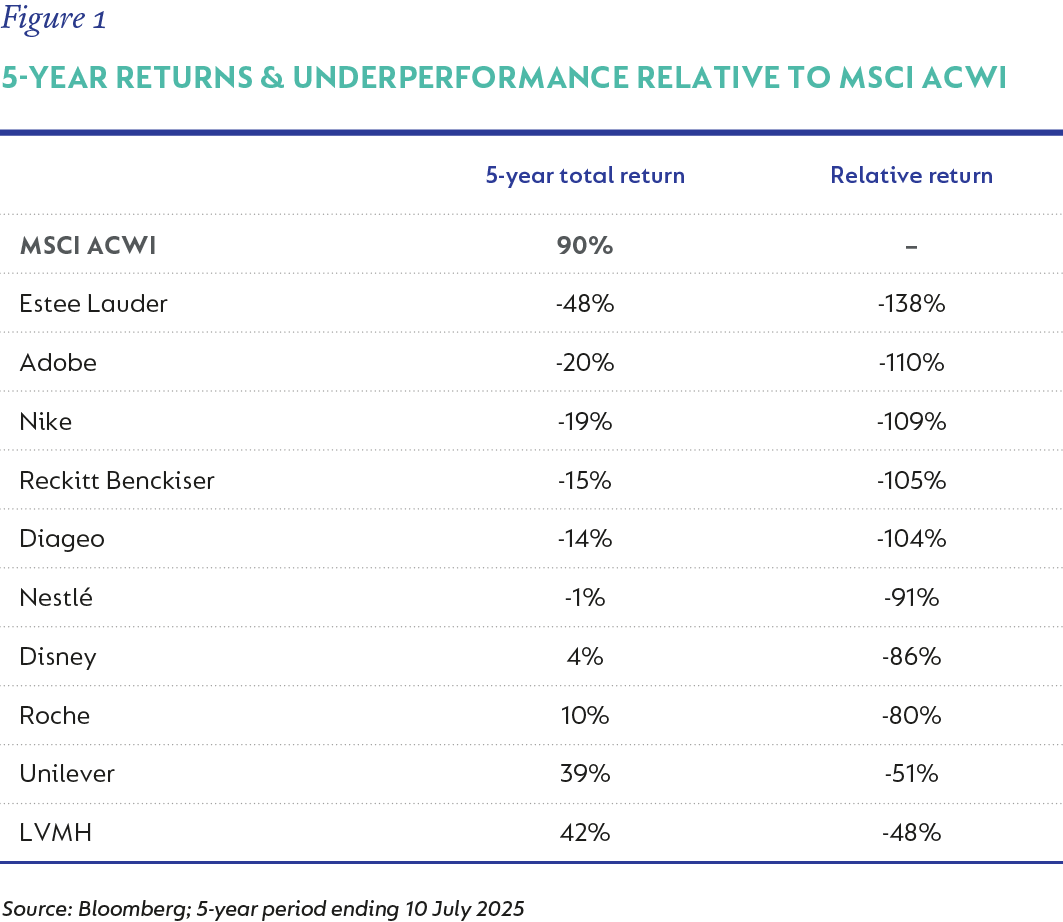

It is no secret that today’s leading businesses will not necessarily be tomorrow’s leaders. We have all read about Nokia, Kodak, and Blockbuster, for example. And it is similarly dangerous to assume that today’s quality stocks will be tomorrow’s quality stocks, as we live in a world where corporate prosperity in the form of ROIC is not guaranteed. Generative AI exploded into the limelight with the launch of ChatGPT in 2022 (Figure 2); this technology is evolving and improving quickly with early use cases evident in coding and software development, customer service, drug discovery, advertising and media production, amongst others; while the automation of business processes has the potential to improve corporate efficiency across the board. This technology has broad potential ramifications across multiple different industries as new use cases emerge. We have no crystal ball in this regard, but over the next decade there will be both winners and losers as a result of this megatrend. In fact, we are already seeing question marks emerge over certain business models in the software and internet space – names like Adobe and Alphabet come to mind. These are businesses that have been considered super high quality up until very recently.

WINNING BUSINESSES

So, how do we think about quality in such a dynamic investment environment? Traditional quality metrics are still important inputs for us, and this, like our investment philosophy, has not changed. But additional questions are necessary. Is the business on the right side of technological change? Does it have a culture of innovation? Does it operate in an industry or market with structural growth tailwinds, and is it a share gainer? Very importantly, has it demonstrated a clear ability to be agile and adapt successfully to changes in its external environment? These factors should enable above-average revenue growth, which is paramount for long-term compounding. ROIC remains key, but we are willing, in certain cases, to look through near-term losses to evaluate the company’s ROIC potential at scale. This allows us to invest, within a broader risk-adjusted portfolio framework, in earlier-stage companies and even loss-making businesses that we view as being well placed for the long term. And what about our assessment of management quality? This is more important than ever in a dynamic investment environment.

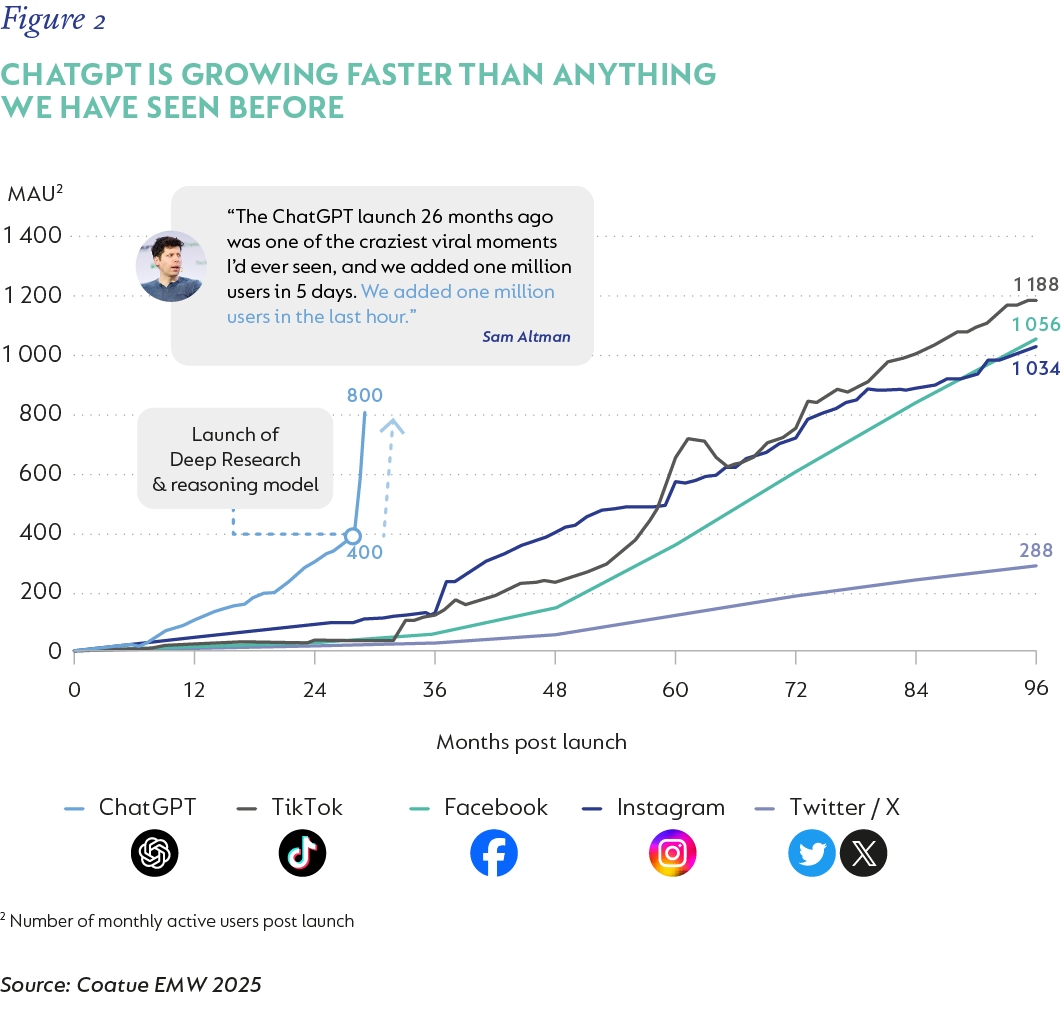

Internally, we call stocks that satisfy the above criteria winning businesses. Spotify is an example of what we would consider a winning business, although this has not always been obvious from the outside. The company has revolutionised audio since its launch in 2008, driving the shift in music consumption to legal paid streaming that rescued the global recorded music industry and returned it to sustainable growth. Yet for years, the business was loss-making, with market participants questioning whether it could “grow up” and transition from being a great product to a great company.

We have long believed that Spotify possesses all the attributes of a winning business, having written about its leading position in the structurally growing music streaming market for the first time in 2018 (Read: Going with the stream ). Its product is best in class, it has a strong competitive position, it boasts a strong growth outlook with significant pricing power and recurring revenue streams, and it is agile with a culture of innovation having already leveraged its platform from music into podcasts, and more recently audiobooks and video. It is led by its exceptional and visionary founder Daniel Ek.

Looking at its losses in isolation, while ignoring its positive unit economics and significant moat-building investments, would have been incorrect. But the business has now also graduated to sustained and healthy profitability, and through a ROIC lens, it screens as ‘off the charts’ as it requires very little incremental capital to grow. Questions around its ability to grow up have now been conclusively answered. As have questions around its ability to compete against big tech competitors like Apple. Spotify has been one of the top contributors to fund returns over most time periods, as we were able to appreciate its winning attributes before the company was able to fully satisfy all traditional quality metrics. Figure 3 illustrates Spotify’s operating margin progression over time.

Interactive Brokers, the US-listed online broker offering clients a platform to trade various asset classes, is another example of a winning business. It achieves very healthy returns on invested capital of around 20% notwithstanding a large net cash balance, has high and stable margins of around 70% on a pre-tax basis, and is growing fast, having grown its number of accounts at over 25% per year over the last decade. But this business earns a large portion of its revenue from net interest margin, which is linked to key policy rates, and is therefore a price taker to an extent. As a result, it doesn’t tick all the traditional quality boxes. But focusing on this only would ignore its incredible moat and strong growth outlook, both of which are enabled by its strong innovation and embrace of technology. As a result of automation and continuous product improvement, Interactive Brokers’ low cost and overall value proposition cannot be matched by its competitors. This is an extremely strong position to be in.

NO ROOM FOR COMPLACENCY

In a world of change and disruption, the classification of businesses cannot be a static endeavour. Ideas and biases need to be challenged, and there is no room for lazy classifications that don’t change with the times. AI will disrupt some of today’s winning businesses, just as many high-quality companies have been disrupted over the last decade.

What impact will autonomous vehicles have on our assessment of the quality of Uber? How will generative AI impact Google’s search monopoly, the competitive position of Adobe’s leading creative software, or the holiday reservation process within Booking.com? And how might growing customer demands for increased convenience and ultra-fast delivery impact Amazon? These questions are not straightforward. Ask two smart people how these shifts will play out, and you will likely get two different answers for each question. The answer also depends on the incumbents’ ability to innovate and adapt to this change.

Therefore, the considerations around what constitutes a winning business must be made in a low ego and pragmatic team environment, where people are allowed and even encouraged to change their minds when the facts change, or simply where a mistake has been made. As Seth Klarman wrote in his famous 2009 letter, The Value of Not Being Sure, “Amidst such uncertainty, people who are too resolute are hell-bent on destruction. Successful investors must temper the arrogance of taking a stand with a large dose of humility, accepting that despite their efforts and care, they may in fact be wrong.”

ENHANCING OUR PROCESS

Tennis legend Roger Federer famously stated that while he won the vast majority of his 1 526 career singles matches, he won only 54% of the points played in those games. Like tennis, a good investor will also make many mistakes, in both good and bad years. The key to positive long-term investment outcomes is, therefore, minimising the impact of one’s mistakes while maximising the impact of one’s good calls. Backing winning businesses makes this easier.

Internally, we have enhanced our investment process to consider the above points. From a quantitative perspective, we now explicitly track the winning business composition across our global equity portfolios. This ratio currently sits at a very healthy 90% and includes a diverse list of names, including ecommerce leaders such as Amazon, Coupang and Mercadolibre; the aerospace names Airbus and Rolls-Royce; Microsoft and Meta in large-cap technology; Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and ASML within semiconductors; European online autos platform Auto1 Group; and Interactive Brokers and Nubank amongst the rate sensitives. Qualitatively, we are getting better at not selling our winning investments too early, as these companies often tend to keep surprising to the upside.

CONCLUSION

Global stock markets are increasingly driven by non-fundamental participants, such as passive funds and short-term focused players, including algorithmic traders and hedge fund pods. This results in significant share-price volatility in the near-term. Against this backdrop, we believe that our long-term focused, valuation-based investment philosophy, where we have a clear sense of what a stock is “worth”, positions us well to take advantage of these market gyrations.

Having a clear sense of whether a business is a winning business builds on this, providing the conviction to act during times of inevitable share price distress in the companies that we own and want to own. But while classifications are important, history has taught us that static definitions are dangerous. A winning business is agile and able to adapt to change in a dynamic world. Successful investors need to be able to do the same.

[1] Originally developed to treat diabetes, but now popular in weight loss, such as Ozempic

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional