Brazil

01 April 2014 - Suhail Suleman

Coronation’s Global Emerging Markets Fund has just over one-quarter of the portfolio invested in Brazilian equities. Given our clean slate, bottom-up approach to building portfolios, it should not be surprising that we are often significantly more exposed to certain countries than the index and many of our peers. In this regard, we are frequently asked why we have significant over-exposure to Brazil today when the short-to-medium term economic outlook looks mediocre at best. Our answer is first and foremost time horizon. One typically comes to a different answer when thinking about a business on a five-year view (as we do) than is the case when thinking about that same business over the next year. Secondly, we make the point that economic growth is typically a very poor indicator of potential investment returns. The most reliable predictor of returns over the long term, in our view, is valuation (the price you pay) combined with the growth in earnings and free cash flow of a business over the long term (not the next one year of earnings). When we assess prospective investments we therefore spend the bulk of our time trying to work out what they will earn over the long term (the ’E’), and then make sure we don’t overpay for this earnings stream (paying the right ‘P/E’).

If we look at the various Brazilian businesses in the portfolio today, we are confident that they are able to grow earnings at a significant rate long term (on average more than 15% per year over five years) and as a basket they are trading on less than 17 times the next year of earnings. In our view, this is a very reasonable multiple to pay given the generally high quality of these businesses (ROE of over 16% for the basket) and the fact that the earnings (both top-line and margins) of many of these businesses are below normal. It would be fair to ask how, with the backdrop of low single-digit economic growth, the stocks that the fund holds in Brazil can achieve this level of earnings growth. In order to answer this, we first need to take a look at some aspects of the country that inform our view on the companies that we follow there.

Brazil is a vast country, smaller only than four others (Russia, Canada, China and the US). Its 200 million population also places it fifth on the world list. After gaining independence from Portugal in 1825 it attracted waves of immigrants from all over the world – São Paulo, for example, is the city with the world’s largest population of ethnic Japanese outside of Japan itself. Despite the appearance to outsiders as a harmonious society, Brazil still grapples to deal with the legacy of its past. It is not well known that the country was the single biggest recipient of slaves from Africa and the last in the western hemisphere to officially abolish the institution of slavery in 1888. Economically, Brazil also had a tumultuous 20th century, with several boom and bust economic cycles, slipping into and out of military governments, and going through repeated periods of hyperinflation that ended only in 1994. It is only really in the last 20 years that the country can be considered a relatively normal, stable democracy.

Despite these recent years of stability, most Brazilian industries remain quite fragmented, with few national champions and high levels of informality. The primary reasons for this is that Brazil’s federal structure transfers significant powers down to the state and local level. Companies wishing to expand outside their home jurisdiction must comply with the requirements of a new government authority for each new state or city they enter. This additional red tape has often not been worth the effort for companies, as the bulk of Brazil’s GDP is generated in just a few small states in the south and south-east of the country. The rest of the country has historically been significantly poorer, providing little incentive for companies to expand outside their southern bases due to the absence of a large consumer class. The high level of informality has resulted in a narrow tax base, which led to high levels of taxation on the formal economy in order to fund the public service. This in turn has discouraged small businesses from formalising, keeping them out of the fiscal net completely and thereby necessitating the continuation of the high tax levels. This unwelcome circle has, until recently, proved difficult to break out of as the informal operators enjoy significant cost advantages over their formal competitors.

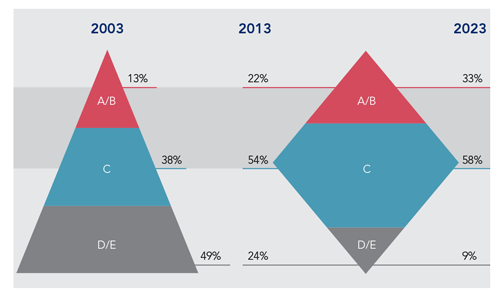

Approximately 12% of the fund’s 27% Brazilian exposure is invested in clothing (Lojas Renner, Hering and Marisa) and food (Pao de Acucar) retailers. These companies will be the prime beneficiaries of the formal market taking share from the informal market. We have spent much time over the last six years speaking to management of these businesses to understand the challenges they face and how they intend to proceed in light of these. In some ways, the difficulty of operating in the type of environment detailed before has made them very astute businesspeople. In our view, the calibre of management is generally among the best in emerging markets – certainly significantly superior to many of the Chinese, Korean and Taiwanese management teams we have encountered to date, where the emphasis is often one of empire building. The common answer from most Brazilian management teams is that, while bureaucracy remains an issue, there are positive long-term developments that will favour the large formal players over the informal ones. First and foremost, the commodity and agriculture boom, coupled with prudent fiscal management, has improved the state of government finances considerably since the current PT party came to power. This has allowed government to expand welfare spending in a targeted fashion, while they have also used the strong economy to increase minimum wages significantly. Normally a sustained increase in minimum wages is accompanied by static or declining employment levels among the lower middle class who earn the minimum wage. Fortunately for Brazil this has not been the case, and unemployment has declined from mid-teen levels to around 5% today. The impact on Brazilian society has been noticeable, with a large reduction in income inequality and a significant increase in the size of the middle class. The graphic below, from a recent presentation by Lojas Renner (a ladies fashion retailer making up 3% of the fund at end of March 2014) illustrates this phenomenon over the last ten years.

Earlier, we asked how Brazil’s mediocre economic growth could be compatible with the sort of long-term earnings growth we expect from the companies we hold in the portfolios we manage on behalf of clients. There are two main reasons we believe this to be the case.

Firstly, the large increase in the number of middle income (or higher) households has created a pool of potential consumers that are currently underserviced. Historical examples, almost universally, show that over time consumers prefer spending in modern retail formats where they are better served, have greater choice, associate strongly with a brand and, if required, can access credit and payment plans. Secondly, the dynamics that held back the formal retail sector are slowly shifting in its favour. State govern-ments are increasingly clamping down on informal retailers to widen their tax base. For several years a campaign has been under way to encourage consumers to report retailers who operate on a cash basis and do not issue official tax receipts. Customers are effectively bribed into asking for tax receipts by the promise that they will get a small rebate on the tax paid if they do so. All they have to do is provide their tax file number to the vendor upon payment and this will be printed on the receipt, which can then be included in their tax return and used to offset some of the taxes owed. I was asked for my tax number at several vendors on a recent trip to Brazil, even though I don’t speak a word of Portuguese and clearly would not pass as a local. Together with many other studies we have seen, this suggests that compliance is becoming increasingly widespread. The structural shift toward compliance will hurt the informal operators as their only advantage over the formal sector is the cost advantage of not paying taxes.

In an environment where the formal sector takes market share from the informal sector, it is possible for company profits to grow at a significantly higher rate than revenue for the industry as whole. Smaller operators make very little money, and over time their revenue will be captured by the larger players whose margins will expand incrementally as their new stores reach maturity and they reap economies of scale. Despite the gloomy outlook many in the market have for Brazil, we have seen a few examples of this dynamic in recent months. Lojas Renner grew profits by 15% last year despite the tough trading conditions experienced by Brazilian retailers, yet the company’s share price has fallen by as much as 30% from early 2013 levels.

Furthermore, we continue to believe profits are well below potential in most of our Brazilian holdings. Marisa (2.7% of fund), whose share price has halved over the last year, has seen operating margins fall to 7%, well below their potential and the recent experience of low double-digit margins. Much of this has been due to poor execution, which we have explored with management in some detail on recent trips and which we believe is being addressed with recent management and systems changes. Marisa trades on 13 times (depressed) forward earnings.

On the non-retail side, Anhanguera Educacional, a private university provider (6.3% of fund), has multiple avenues to expand profits over time. Its campuses are largely empty during the day as their core customers are young working adults studying part time after hours. They can therefore add significant student numbers with little additional capital expenditure. Margins also have significant scope for expansion. Campuses acquired through mergers and acquisitions three years ago still earn gross margins 20% below Anhanguera’s organic campuses. Anhanguera trades at 10 times what we believe it will earn in three years. It is quite likely the company will merge with industry leader Kroton unless there are significant antitrust hurdles, which will provide further scale benefits and synergy savings for the combined group.

Overall, Brazil remains something of an enigma. It is a country with great long-term potential and many world-class businesses that are currently disliked by the general market. Focusing on short-term macro-economic issues is very prevalent and this has created opportunities for us as long-term investors. We expect the fund’s Brazilian exposure to be a valuable source of returns over time.

SUHAIL SULEMAN joined Coronation’s Emerging Markets team in 2007, initially covering the consumer and industrial industries. He currently co-manages the range of Global Emerging Markets funds. Suhail has 12 years’ investment experience.

If you require any further information, please contact:

Louise Pelser

T: +27 21 680 2216

M: +27 76 282 3995

E: lpelser@coronation.co.za

Notes to the editor:

Coronation Fund Managers Limited is one of southern Africa’s most successful third-party fund management companies. As a pure fund management business it provides individual and institutional investors with expertise across Developed Markets, Emerging Markets and Africa. Clients include some of the largest retirement funds, medical schemes and multi-manager companies in South Africa, many of the major banking and insurance groups, selected investment advisory businesses, prominent independent financial advisors, high-net worth individuals and direct unit trust accounts. We are 25% staff-owned, have offices in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Durban, Gaborone, Windhoek, London and Dublin and are listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. As at the March 2014 quarter-end, assets under management total R547 billion.

Disclaimer:

All information and opinions provided are of a general nature and are not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Coronation is not acting and does not purport to act in any way as an advisor. Any representation or opinion is provided for information purposes only. Collective Investment Schemes in Securities (Unit trusts) are generally medium to long term investments. The value of participatory interests (units) may go down as well as up and past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. Coronation Fund Managers will not be held liable or responsible for any direct or consequential loss or damage suffered by any party as a result of that party acting on or failing to act on the basis of the information provided in this document. Coronation Asset Management (Pty) Ltd is an authorised Financial Services Provider (FSP no. 548).

South Africa - Institutional

South Africa - Institutional