Nigeria: Addicted to dollars - July 2016

Addiction. A word that can conjure up a multiplicity of emotions, including euphoric highs and heart-breaking failures. Whether we care to admit it or not, in some way most of us are addicted to something: love, work, social media, alcohol, coffee, status or food. Some ‘substances’ may be more socially acceptable than others, and in measured doses, some of these addictions may be good for us, but there comes a point where we develop an unhealthy reliance on our vice of choice. Take that stimulant away and we slowly fall apart.

Nigeria is addicted to dollars. Over the past 18 months, the government has had to figure out how best to respond to much less of its regular hit.

Nigeria, like other oil producers, is deeply reliant on oil revenue. Not only does oil account for more than 80% of its fiscal revenue, but with oil representing close to 90% of exports, it is effectively its only source of dollar income. These dollars are then used to pay for Nigeria’s large import bill. The import bill is large because Nigeria produces very little locally. A steady stream of dollars is thus vital to ensure that the population is fed, clothed and able to move around. It is also vital to ensure that businesses can access raw materials and the equipment that they need to function. With the collapse in oil prices, and cut off from dollars, Nigeria’s economy has become deeply strained. The impact of going cold turkey has been harsh: the current account fell into a deficit of -3.3% of GDP, the first deficit in 13 years; the trade balance turned negative for the first time in 30 years; and oil-related foreign direct investment collapsed.

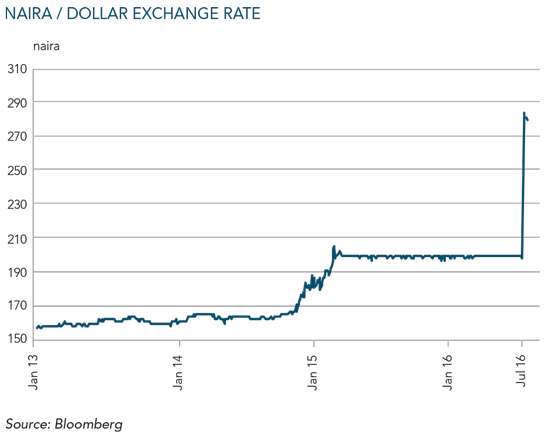

Nigeria’s economic fundamentals saw a meaningful deterioration, but unlike other oil producers that allow their currencies to weaken, Nigeria’s policy response was to hold the naira painfully stable, resulting in a very overvalued currency. Government contended that fixing the currency would limit the impact of inflation on the economy and protect the poor from rising food prices. Unfortunately, it effectively led to a seizure in the foreign exchange market and many businesses were forced to buy dollars through unofficial channels, where rates were 50% to 100% higher than the official rate. This meant that inflation rose regardless. In order to hold the pegged exchange rate, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) implemented an array of restrictions, including a long list of import controls. This forced even more businesses into the unofficial market. The net result has been a sharp rise in inflation and a decline in growth. Inflation was 15.6% year-on-year in May and GDP growth in the first quarter of 2016 was -0.4% year-on-year and is forecast to contract almost -2% in real terms for the year as a whole.

The cost of defending the naira finally became too much to bear and the currency was allowed to float in June. We view this as a positive development, as we believe that the level of the exchange rate is far less important than the requirement for dollars to be accessible in the market. Businesses are surprisingly resilient and are generally able to deal with a sharp rise in costs, either through passing on price increases, cutting costs or accepting lower margins. However, resilient businesses cannot survive if the raw materials or machinery they need to produce their products suddenly become unavailable. This is what happens when they cannot access dollars; businesses that rely on imported raw materials grind to a halt. Assuming the CBN allows the naira to find a rate that fully reflects its real market value in coming months, the economy is likely to go through a painful, but necessary, adjustment. The first impact will be higher inflation in an environment where prices are already rising.

We would expect the CBN to respond by increasing the monetary policy rate by some 200 to 300 basis points over the next year. At the same time, the external balance should adjust, providing some reprieve and better support for growth. A currency that is completely free-floating and that is more reflective of fundamentals should support confidence in not only the value, but also the convertibility, of the currency.

Admittedly it is still early days in the new regime, but our initial euphoria over Nigeria’s move towards a freer exchange rate is waning. Liquidity has continued to be severely constrained and the rate of exchange has been stubbornly steady around N280 to the dollar. The market remains opaque, with limited visibility into its inner workings. An obvious question at the moment is whether Nigera has truly moved to a floating exchange rate or whether the CBN is managing the float, allowing for a one-off 40% devaluation, but now continuing to maintain the peg, albeit at a lower level. The risk with a ‘managed float’ is that the underlying problem (dollar shortages in the economy) is not addressed and the limited access to dollars will ultimately strangle the economy once again.

As the manager of an Africa-focused fund, it is difficult to ignore a country like Nigeria, and over the medium to long term, we still believe that Nigeria is one of the most attractive markets globally. Unsurprisingly, we have seldom struggled to find high-quality companies trading at attractive valuations on the Lagos bourse. However, given the policy response of president Muhammadu Buhari’s administration to the decline in oil prices, we have spent the better part of the last 18 months debating how best we should respond in our portfolios.

At this point, it is worth noting that our investment methodology is very much a long-term, bottom-up, valuation-driven one. Exchange rates and currencies are taken into account in our earnings forecasts, but are viewed admittedly as ‘low-conviction’ inputs. We simply have never been very good at calling short-term fluctuations in currencies. Our competitive advantage is our long-term investment horizon and our valuation-driven philosophy, not our view on a particular currency. With that caveat out of the way, how did we position ourselves?

Our approach was as follows:

Reduce our position size

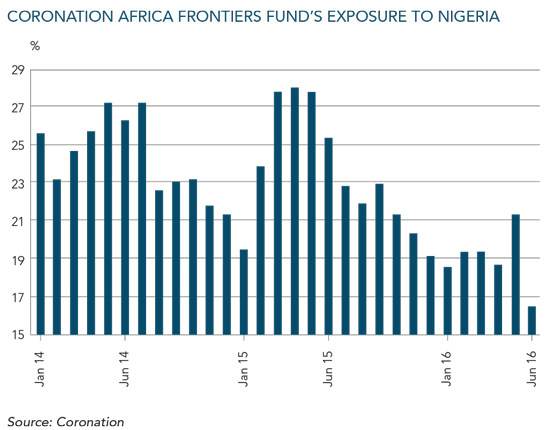

As the oil price started falling in the second half of 2014, equity valuations began to look stretched and our earnings forecasts started to decline. We took a decision to reduce our Nigerian exposure from a high of 27.4% of our Africa Frontiers Fund in July 2014 to 19.6% in January 2015.

Following the move to reduce our exposure to Nigeria, the market sold off significantly in the run-up to the March 2015 election. With valuations looking attractive, we added to some of our positions, increasing our Nigeria exposure, resulting in Nigeria once again representing 27% of fund. This investment allowed us to benefit from the strong market gains following the peaceful transition to the Buhari administration. The large market gains pushed some of our holdings to close to our estimate of their fair value. Accordingly, we reduced our portfolio exposure to below 20% once again. At the time, there were still enough dollars in the market to enable this withdrawal and we could repatriate our naira sales. We also increased our cash holding at this time.

Hedge the naira

In November 2014, with oil prices continuing to fall rapidly and the naira stubbornly pegged at N168 to the dollar, we entered into a hedge for 20% of our Nigerian exposure. This allowed us to further reduce our naira position without having to physically sell the underlying shares. In hindsight, while the hedge worked very well for us, we should have hedged a far greater proportion of our exposure.

Switch exposure to foreign listings

As dollar liquidity in the market dried up in the second half of 2015 and concern grew around our ability to repatriate returns from any sales, we took an active decision to move our exposure in dual-listed companies from listings on the Lagos exchange to the equivalent listings in London or New York. This allowed us to continue to trade these shares without worrying whether the de facto capital controls in Nigeria would persist.

Avoid cash

Over the course of 2016, it became apparent that it would be very difficult to repatriate any naira into dollars. We were effectively stuck with the naira we had invested in Nigeria. While we waited for the inevitable devaluation, the very worst place to be would be in cash. Any devaluation would see the fund take a guaranteed loss. A far better place to hide was in equities, which we expected would see a relief rally following any currency move.

Avoid companies that short dollars

The final adjustment to our portfolios was to switch out of companies that were naturally shorting dollars or were exposed to the Nigerian consumer, and buy companies that stand to benefit from a naira devaluation. This saw us sell out of a number of counters that have dollar payables or have large import bills. A company that we have been adding to in this environment is Dangote Cement. Dangote is commissioning cement plants across the continent, resulting in dollar revenues increasing as a percentage of its sales. Any naira devaluation would benefit Dangote, as the company earns 30% of its revenue from international operations, cushioning any rising import costs.

Whether Nigeria will learn from the latest oil shock and pursue more appropriate policy responses going forward is yet to be seen. The Buhari government has certainly taken a step in the right direction by allowing the naira to float and we believe that their intentions are good. However, good intentions, as any addict knows, are largely worthless. What Nigeria needs is for the currency to float freely and for a market-determined exchange rate to attract an inflow of dollars once again.

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal