Investment views

Silk road 2.0: China’s quiet conquest of tech and trade

“Policy done right can drive technological disruption.” - Akshat Rathi

The Quick Take

- China’s tech-industrial ecosystem evolved as an interwoven network; success in one domain reinforced progress in others

- Chinese tech champions often emerge from concerted State-industry collaboration rather than pure market competition

- China’s coordinated, whole-nation approach gives it the edge over Western rivals operating in fragmented private markets, accelerating both technological evolution and scale

- Tariffs and sanctions are the visible symptoms of a deeper strategic contest; the real story is China’s patient, long-cycle industrial strategy that continues to reshape global supply chains

- To be clear, this is leading-edge innovation, not just scale – for instance, CATL’s recent battery and charge speed breakthroughs

THE INVESTMENT TAKE

China’s listed tech leaders, from BYD and Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL) to Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) and Huawei’s supplier network, are not simply domestic players but global disruptors, commanding leadership positions in EVs, batteries, solar, 5G, AI and more recently robotics infrastructure. Yet their market valuations remain deeply discounted, reflecting geopolitical anxiety rather than underlying business strength. These are world-class businesses with strong earnings power, global customer bases and a proven ability to innovate under pressure. A rare combination that is often overlooked amid the prevailing political narrative.

Global rivalries have long served as the crucible for breakthrough innovation and today, the escalating trade tensions between China and the United States form the backdrop to a new industrial revolution, one defined not only by competition over artificial intelligence (AI), chips, and electric vehicles (EVs), but by divergent national strategies. Where Washington has wielded tariffs and sanctions in hopes of stalling China’s ascent, Beijing has interpreted pressure as fuel, using adversity to accelerate innovation, reorient supply chains, and scale industrial ecosystems.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the current wave of Chinese breakthroughs, from XPeng’s in-house autonomous driving chip to CATL’s hot-off-the-press sodium-ion and dual chemistry batteries, superfast charging technology (capable of delivering 520 kilometres of range in just five minutes), and rapid commercialisation cycle. These advances are not simply about catching up, they are redefining global standards and challenging assumptions about where true innovation resides.

Ironically, one of the clearest illustrations of this geopolitical divide is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), a company rooted in Chinese-speaking Asia that has become a strategic asset of the United States. Through heavy federal subsidies and onshoring incentives, the US is now effectively “nationalising” a pillar of global chip supply, positioning TSMC fabrication plants (FABs) in Arizona as a hedge against supply chain vulnerabilities and Chinese influence. In doing so, Washington has acknowledged just how critical semiconductor capacity is in this new era, even if it means reshaping corporate allegiances. This quiet redrawing of industrial maps reveals that technological sovereignty is no longer abstract; it’s physical, political, and increasingly nationalised.

While the West has often underestimated China’s technological ascent, viewing it largely as a story of scale and State-led execution, this narrative is increasingly outdated. Chinese firms like Huawei, CATL, BYD, and even SMIC have proven themselves to be genuine global innovators, not just beneficiaries of protectionist policy or domestic market size. Their success points to a more fundamental truth: China is producing some of the world’s most formidable technology companies, led by management teams that have demonstrated extraordinary agility and resilience, even under intense geopolitical pressure. Huawei's recent performance exemplifies Chinese resilience in the face of US sanctions. In 2024, the company reported a 22.4% year-on-year revenue increase, reaching ¥862 billion (US$118 billion), marking its fastest growth in five years and nearing its 2020 peak of ¥891 billion.

To dismiss China as “uninvestable” due to political risk, concerns around property rights or lack of western democracy may be convenient, but it is increasingly an oversimplification. In reality, the opportunity set is growing more global in character. Investors used to look to China for the best-positioned domestic players; now, many of the world’s leading companies, in batteries, EVs, telecoms, and increasingly robotics, just happen to be based in China.

Indeed, the next wave of global disruption may come from robotics, where China’s leadership is rapidly solidifying. With breakthroughs in industrial automation, AI-robotic integration, and smart manufacturing, China is poised to lead a sector that will rival AI in transformative impact.

Rather than being derailed by external shocks like the Trump tariff war, China has responded with a deeper, more coordinated push toward technological self-sufficiency, a high-stakes gambit that may well redefine the rules of global competition.

WAN GANG’S ELECTRIC DREAM

In 2007, a quiet revolution was set in motion. Wan Gang – an automotive engineer who had spent a decade at Audi in Germany – was appointed China’s Minister of Science and Technology. It was a highly unusual choice. Wan was not even a Communist Party member. He brought an audacious vision: to electrify China’s automotive future. Once in office, he aggressively steered industrial policy in the direction of electric vehicles (EVs), a move that was firmly backed by the State. Wan’s policy toolkit – from procurement contracts to purchase incentives – created a protected incubator for EV startups. By 2009, generous subsidies, tax breaks, and research funding were implemented to bolster the sector and align innovation. The results were dramatic.[1].

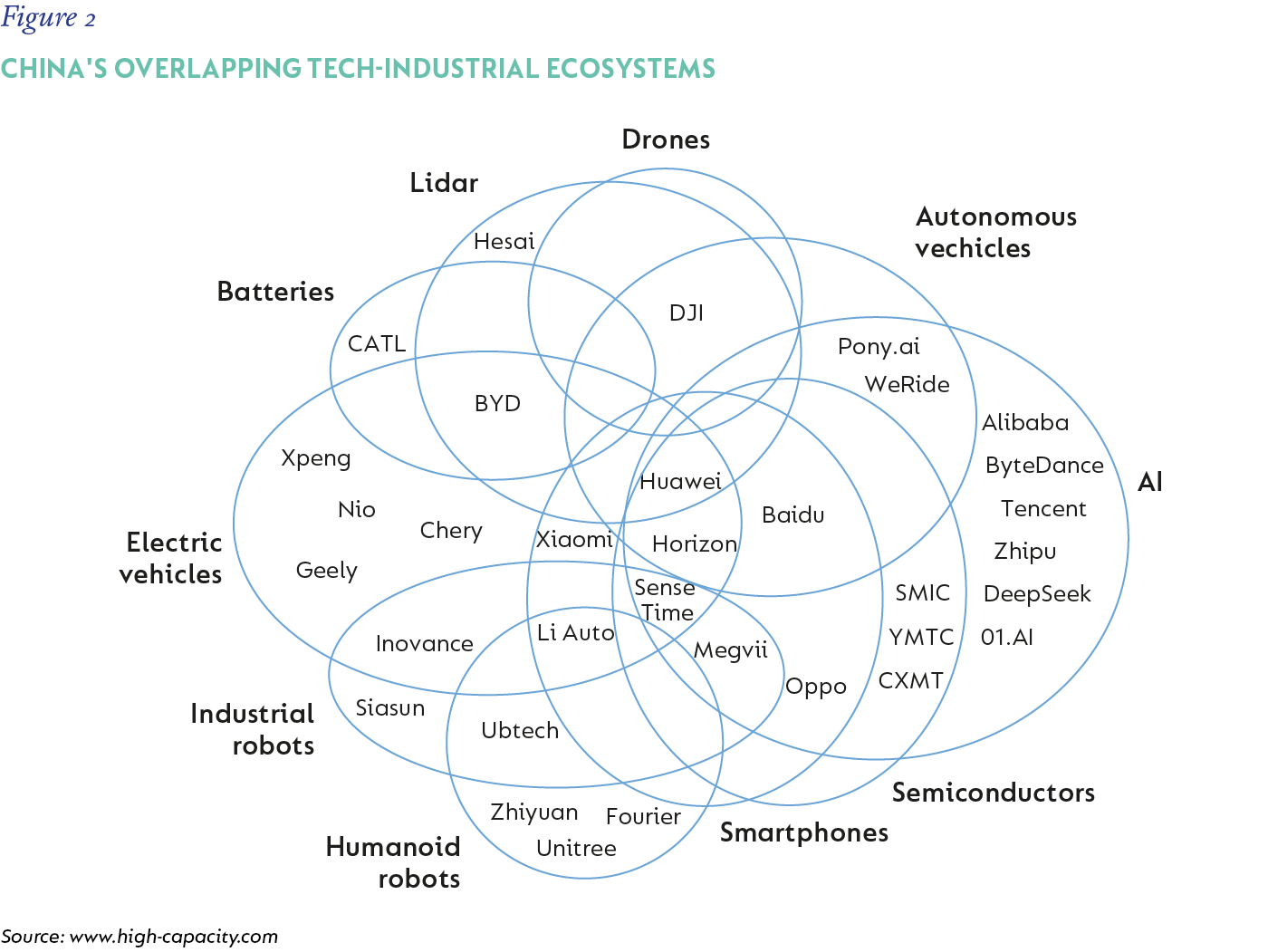

Between 2009 and 2022, Chinese EV sales ramped up from 500 cars to more than six million, accounting for more than half of global EV sales. Today, Chinese automakers have dominated the field for eight years and produce roughly two-thirds of the world’s EVs – an almost unthinkable achievement in just over a decade. Almost in tandem, battery giants like CATL (the world’s largest battery maker) and BYD (which produced batteries before cars) expanded rapidly under these policies, scaling up on the back of booming EV demand. In turn, mass production drove down battery costs, rendering EVs ever more affordable – a virtuous cycle that Wan had envisioned from the start. By focusing the might of the State on this strategic sector, China has outstripped the global automotive industry in the transition to electric mobility. Figure 1 indicates an astonishing increase in Chinese car production from just 1% to 39% of global market share in just two decades.

BUILDING AN INDUSTRIAL TECH ECOSYSTEM

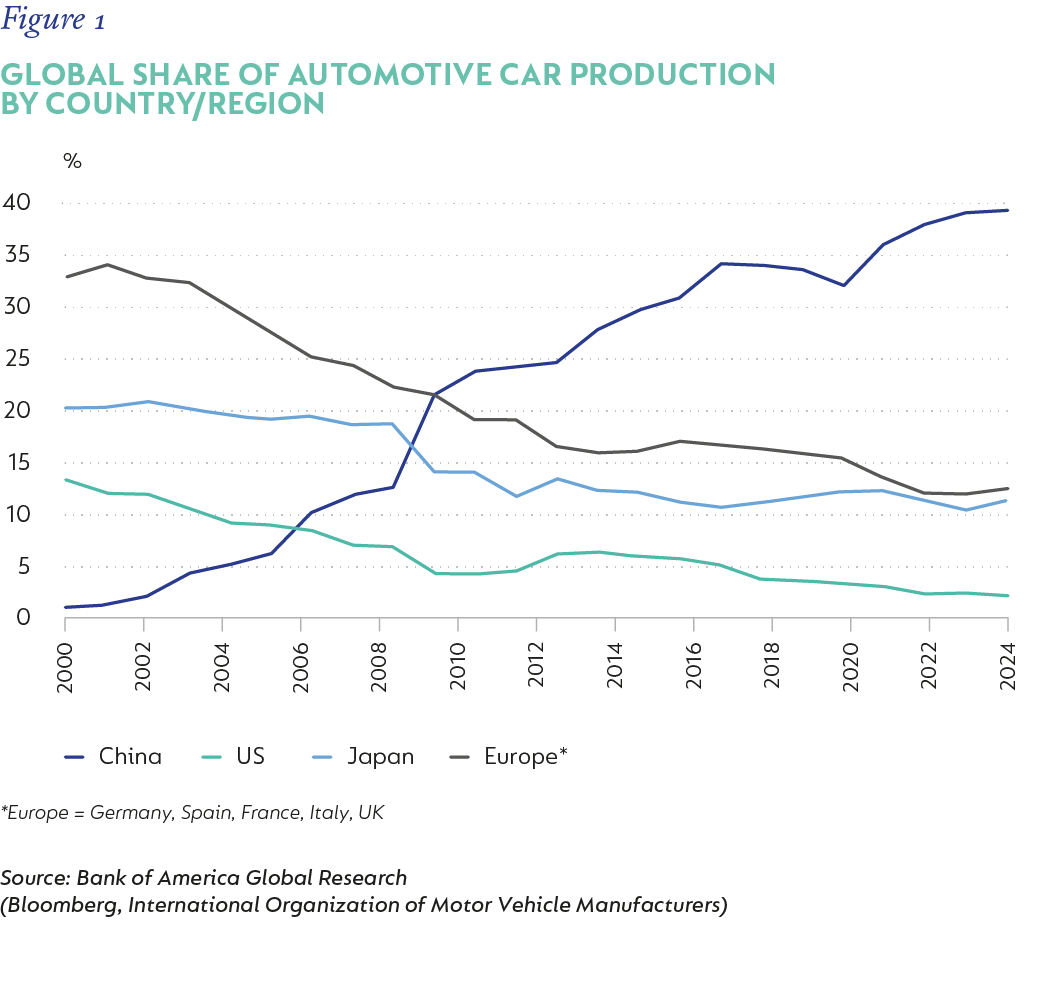

The EV sector was just the first of several in which China built scale and expertise, adeptly leveraging existing capabilities to embrace the new. And so began the evolution of a tightly interwoven tech-industrial ecosystem, where successes in one domain reinforced progress in others. The net effect is an impressive, vertically integrated supply chain that extends from mineral mining through to end products[2].

For instance, the smartphone boom of the 2010s endowed China with world-class electronics manufacturing capabilities (think Foxconn and Huawei). This enabled those same assembly lines and suppliers to swiftly pivot to EV and battery production. This is a path that BYD followed directly, leveraging its mobile battery and internal combustion engine automotive expertise to become a battery and EV producer, outstripping Tesla in unit sales and revenue in 2024.

The synergies are everywhere, and economies of scale amplify China’s competitive advantage. The massive scale in manufacturing means components such as sensors, power electronics, and chips can be sourced cheaply and in bulk. Factories churning out millions of smartphones and solar panels created a domestic supplier base that EV startups could tap into, slashing costs. Meanwhile, the battery innovations spurred by electric cars have spilt over into other arenas. These batteries now drive China’s energy storage projects and power smart appliances and devices, further expanding scale.

A key example is the renewable energy and EV nexus overlap. The government’s heavy investment in solar power and the construction of the world’s largest charging network (c. 3.2 million public charging points by mid-2024) created an abundant, ultra-cheap solar energy supply system. This created capacity for millions of new EVs, making them more economically viable and sustainable.

China’s installed solar capacity rocketed from about 250 GW in 2020 to 650 GW by early 2024. In 2024 alone, 277 GW of solar capacity was added to the grid – more than the US’s total installed solar power capacity. This clean energy boom is not just a green virtue; it directly lowers electricity costs for China’s manufacturers. Industrial power in China can cost as little as US$0.05–US$0.07 per kWh, compared to US$0.09–US$0.13 in the US.

Cheap energy at scale provides a significant competitive edge to energy-intensive sectors like battery gigafactories and semiconductor FABs. Even 5G infrastructure, where firms like Huawei lead globally, ties into this ecosystem, enabling the connected cars and smart factories that further drive demand for chips and software. The Chinese model showcases how coordinated industrial policy integrates energy, transportation, and digital tech into a formidable engine of economic power. Each sector’s advancement reinforces the others in a way that resembles a modern, high-tech Silk Road – an integrated network of trade and technology radiating from China (Figure 2).

ALPHAGO AND THE AI “SPUTNIK MOMENT”

A seminal event in May 2017 reshaped the country’s high-tech ambitions: a board game match. China’s 19-year-old Go master Ke Jie was defeated by AlphaGo, an artificial intelligence (AI) programme from Google’s DeepMind. This highly publicised man-vs-machine showdown was dubbed “China’s Sputnik moment”, with a jolt akin to the 1957 Soviet satellite launch that spurred the US space race[3].

It was game on for Beijing, which wasted no time formulating a response. Just two months later, the State Council issued a national AI development plan, declaring an ambitious goal for China to become “the world’s primary AI innovation centre” by 2030. A massive wave of investment and entrepreneurship in AI followed. By the end of 2017, Chinese startups and tech giants were drawing nearly half of all global AI venture funding. Tech entrepreneur Kai-Fu Lee describes Chinese entrepreneurs at the time as seizing a once-in-a-generation opportunity, leveraging China’s huge datasets and hungry venture capital to chase AI applications in everything from healthcare to finance. The government poured funds into research institutes, companies, and talent programmes to ensure China would catch up in fundamental AI research.

Crucially, this AI push did not happen in isolation – it built on the existing technology foundations that provided the hardware backbone and utilised the ocean of Chinese digital data for AI algorithms to learn from. Abundant cheap and sustainable energy meant AI data centres could be powered affordably, an oft-overlooked edge in the energy-hungry deep learning era. The earlier success in EVs gave China confidence that, with State support, it could crack any frontier technology. From 2017 onward, AI joined the pantheon of industries – alongside EVs, batteries, and solar – that China would pursue with characteristic coordination.

SILICON SQUEEZE: CHIPS AND THE QUEST FOR SELF-RELIANCE

No discussion of China’s tech ascent is complete without semiconductors – the “brains” powering smartphones, EVs, and AI alike. For years, cutting-edge chips were a weak link in China’s tech ecosystem. Domestic FABs lagged industry leaders like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company by generations, and China imported over US$300 billion worth of devices annually.

When the US began restricting chip exports to China, this became a huge liability. Starting in 2018 and escalating through 2020–2022, US sanctions denied Huawei and other tech firms access to advanced chips and manufacturing tools, aiming to stall China’s progress. It was a harsh wake-up call, but it reinforced Beijing’s resolve to achieve semiconductor self-sufficiency. Sanctions became a “double-edged sword”, as Kai-Fu Lee observed. They created short-term pain but forced Chinese companies to innovate under constraints.[4].

True to form, China launched a whole-of-nation effort on chips. State funds flowed to FABs and chip design startups; university programmes swelled with semiconductor students; tech giants like Alibaba and Huawei set up chip design divisions. Progress was arduous, but in 2023, Huawei stunned the tech world by releasing its Mate 60 Pro smartphone with a domestically produced 7-nanometer processor, built by Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC) despite US export controls. Its Kirin 9000s chip was the most advanced Chinese-made chip to date. While still a node or two behind the latest US chips, it proved that ingenuity under pressure gets results. The symbolism of the achievement was enormous: China was cracking the silicon ceiling.

Huawei’s feat hints at what is coming. The company has reportedly marshalled thousands of engineers to develop semiconductor design tools and alternative production techniques. Other firms, from AI chip startups to legacy players like SMIC, are likewise racing to overcome technological barriers which, once achieved, will be a massive disruption. For now, high-end semiconductor production remains one of the few arenas where China trails its global peers. It’s a tough problem. But the gap is narrowing. Washington’s restrictions, paradoxically, have galvanised Beijing’s determination to control its “silicon destiny”. Should China succeed, it will complete a vertically integrated tech supply chain unrivalled in scope – from energy to materials to finished electronics – truly a Silk Road 2.0, spanning cutting-edge trade.

THE OPEN-SOURCE AI DISRUPTION

The debut of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in 2022 was the next inflexion point, sparking a global AI frenzy. Almost immediately, Chinese tech giants (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) and a crop of startups scrambled to develop large language models. Early Chinese offerings significantly lagged those of Silicon Valley, resulting in a palpable sense of “AI fever” and frustration. Then, in late 2024, a relatively unknown Chinese startup called DeepSeek upended the narrative.

DeepSeek’s secret sauce was its embrace of open-source AI models that were efficient and cheap to train. It was on par with the best American models but was trained for under US$6 million using off-the-shelf Nvidia H800 chips. Compared to top-tier AI models that had required tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in computing power, it was a bombshell. Even more shocking, DeepSeek’s AI assistant app surged to become the top-rated free app on Apple’s App Store in the US, briefly overtaking ChatGPT in popularity. Out of the blue, a free-to-use Chinese model was matching US AI models at a fraction of the cost[5].

By early 2025, DeepSeek had ignited an open-source AI wave and was reported to be 20 to 50 times cheaper on a per-task basis than OpenAI. Chinese companies raced to integrate these free, high-quality models into their products and services. Automakers like Great Wall and BYD began embedding it into their smart car interfaces, adding advanced conversational features without the hefty cloud AI bills. Telecom giants (China Mobile, China Unicom) deployed it for customer service and network optimisation. It was a broad-based adoption that only a large, unified ecosystem like China’s could achieve so quickly. DeepSeek is now the default AI engine for a range of domestic industries.

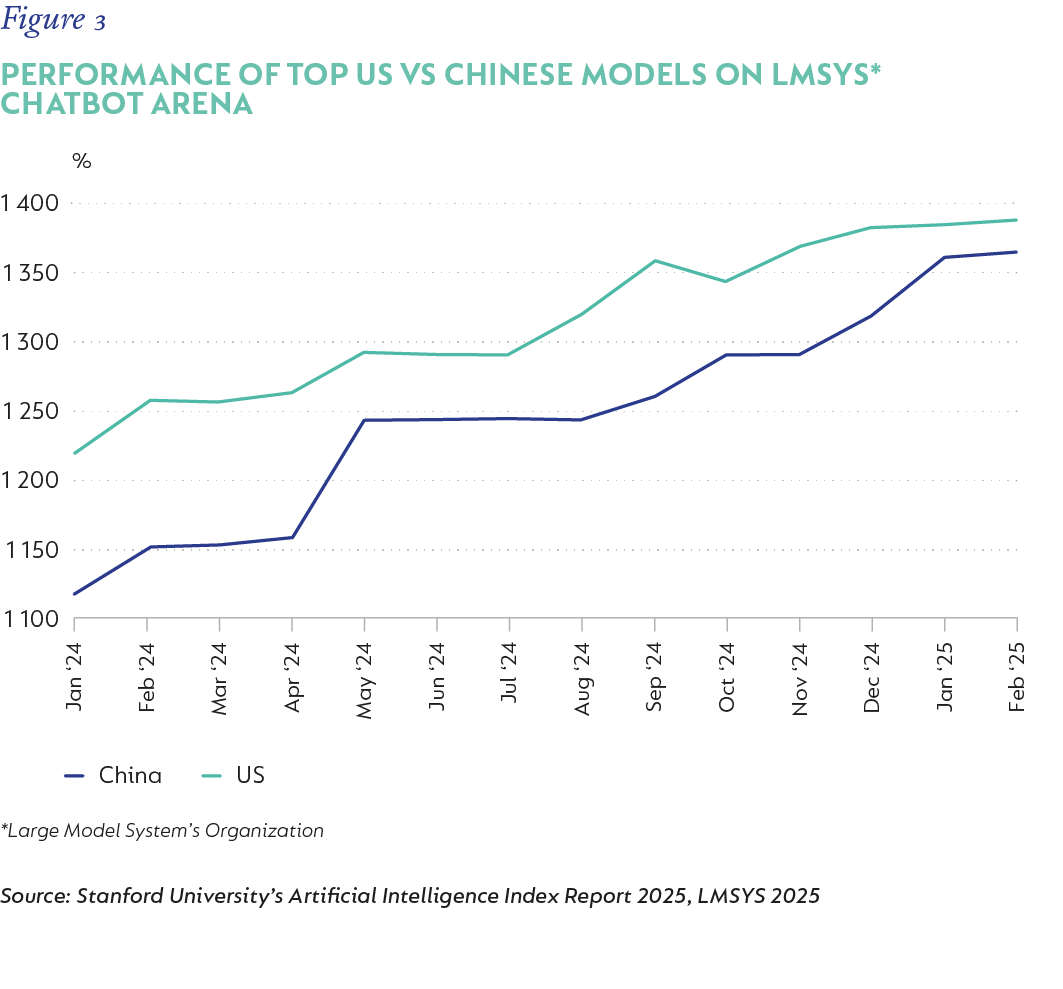

By slashing costs, DeepSeek also supercharged innovation. Startups and researchers can build on the good-enough models to create domain-specific AI applications across sectors without needing a Silicon Valley budget. In turn, this broad usage feeds back into improvements and training data for the models, accelerating their improvement. This crowd-sourced, decentralised AI model contrasts with the West’s corporate-driven approach. It draws on China’s strengths – a deep talent pool and a market that can implement and iterate at scale. In sum, the DeepSeek saga illustrates how deftly China’s tech ecosystem can adapt and capitalise on innovation, turning a global tech trend to its advantage. What started with Wan Gang’s EV vision has evolved into a multi-headed hydra of tech prowess – from batteries to bytes – each part reinforcing the whole. Figure 3 illustrates the improvement of both US and Chinese AI models, and also notably the pace at which China has caught up with US competitors.

COORDINATED STRATEGY VS. FRAGMENTED EFFORTS

Beijing’s coordinated, long-term industrial strategy reflects a fundamental strategic difference versus a more fragmented, market-led approach in the West. The playbook involves the government setting a clear goal (like EVs or AI supremacy) and then marshalling resources across ministries, State banks, and private companies to achieve scale. This includes heavy upfront investment – subsidies, grants, and infrastructure – to bolster industries until they can stand on their own[6]. Crucially, policies are consistent over time. EV subsidies, for instance, ran for over a decade and only phased out once China achieved cost parity and dominance. Even then, they were replaced by other incentives to ensure momentum. Policy continuity and clarity have given companies the confidence to make big bets on new technologies.

By contrast, the US has relied on the private sector to drive innovation, with limited government intervention. This has yielded incredible successes, but also gaps in coordination. It is only recently that the US government, spurred largely by the threat of China’s rise, has stepped in with initiatives like the 2022 CHIPS Act (to boost semiconductor manufacturing) or the Inflation Reduction Act (with EV and clean energy credits). Moreover, policy and federal support wax and wane with administrations, while legal battles and lobbying dilute implementation.

As a result, US firms have often had to navigate new commercial paths alone, leading to a more fragmented approach. For example, Tesla's rise was spurred by Elon Musk’s vision and Silicon Valley capital rather than government policy. Similarly, AI progressed with private funding and Big Tech backing. This decentralised innovation model produces brilliant breakthroughs but struggles to scale infrastructure-heavy industries such as batteries and solar with China’s speed and coordination.

The effects of these divergent strategies are now visible in global markets. China’s synergistic approach has made it the indispensable supplier of the green and smart technologies that will define the 21st-century economy. Nearly 80% of solar panels come from China, it leads in EV battery production and is a global player in 5G, while DeepSeek is eroding the first-mover advantage of OpenAI.

For investors, this suggests that China’s tech sector is a linked ecosystem backed by strategic policy that can achieve rapid scale-up and cost advantages. It is a more predictable growth trajectory in some respects, though not without risks (e.g., over-investment or geopolitical backlash). By contrast, US tech successes tend to spring from more unpredictable innovation cycles and face more domestic uncertainty, such as shifting regulations on issues like EV tax credits and AI governance.

SILK ROAD 2.0: FROM DOMINANCE TO INFLUENCE

China’s quiet conquest of key tech and trade sectors is coming into full view. What started with Wan Gang’s EV dream has expanded into a broad-based industrial and technological supremacy in emerging industries. This new trade route is paved with technology standards and trade relationships that increasingly favour Beijing.

This influence is quiet but decisive. China’s tech conquest often happens at the consumer and enterprise level – a European driver choosing a NIO EV or an African telecom operator buying Huawei 5G equipment. These choices, backed by the cost-efficiency of scale, incrementally lock in China’s role as an indispensable partner.

From an investment perspective, the story of “Silk Road 2.0” is a story of shifting competitive moats. China’s quiet conquerors thrive on an integrated home base, scale, and patient capital, rather than just breakthrough innovation. The US, still the global leader in fundamental innovation and research, now finds itself in the unfamiliar position of playing catch-up in scale commercialisation and deployment.

In the US, the growing recognition that a more cohesive strategy is needed is apparent in new semiconductor FABs breaking ground in Arizona, or the rush of EV battery plants across the American South and Midwest spurred by federal incentives. But coordination takes time, and time is what China maximised over the past two decades by starting early in key tech races. An escalating tariff war is more indicative of late-stage desperation than a recognition of the hard work required to balance the reciprocal value of trade.

As China consolidates its gains, we would be remiss not to highlight that risks remain. Externally, geopolitical tensions will lead to trade barriers (witness the EU’s recent probes into Chinese EV subsidies, or US export bans). Internally, China must balance its top-down directives with market forces – there have been periods of overcapacity and waste. However, the tech-industrial sectors discussed – EVs, renewables, digital tech – align closely with China’s long-term development goals (energy security, sustainable growth, tech self-reliance), so they are likely to enjoy continued support rather than abrupt policy reversals. And they offer great value to other customer countries.

The lessons from China’s trajectory are sobering for its rivals. Tariffs and sanctions, intended as brakes, have often functioned as accelerants. By imposing constraints, Washington has inadvertently sharpened Beijing’s resolve, propelling Chinese firms to build new capabilities, scale new industries, and forge new trade corridors.

The old Silk Road brought goods and culture from East to West. The new Silk Road, forged from semiconductors, batteries, code, and solar cells, may bring influence and standards. The shift is already underway. The only question now is whether others will catch up, or merely react to China’s pace-setting lead.

In conclusion, the narrative from Wan Gang’s 2007 gamble on electric cars to DeepSeek exemplifies China’s strategic march. It has been a journey of patient planning, learning by doing, and scaling up at a pace the world has never seen.

[1] Zeyi Yang, “How did China come to dominate the world of electric cars?”, MIT Technology Review, 21 February 2023

[2] Kyle Chan, “China's overlapping tech-industrial ecosystems,” www.highcapacity.com, 22 January 2025

[3] Dan Milmo “TechScape: how China became an AI superpower ready to take on the United States,” The Guardian, 8 December 2021

[4] Liam Mo & Kane Wu, “DeepSeek narrows China-US AI gap to three months, 01.A1 founder Lee Kai-fu says,” Reuters, 25 March 2025

[5] Eduardo Baptista, “What is DeepSeek and why is it disrupting the AI sector?”, Reuters, 28 January 2025

[6] Stephen Ezell, “How Innovative Is China in the Electric Vehicle and Battery Industries?”, Information and Technology Foundation, 29 July 2024

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal