It has been another brutal year. The economy has suffered the effects of political uncertainty which tightened its grip throughout the year and extended 2016’s miserable performance. At a glance, it is hard not to notice that an alarming number of SA’s economic metrics are back at levels that prevailed in 1994. Growth is set to average 1.4% over the last five years, assuming we manage even 1% in 2017, in a world which is growing at 3.6% (IMF estimate). This is below the 2.6% which prevailed from 1995 to 2000 (and that period included a series of emerging financial crises), although better than growth of 0.2% during the years before the first democratic election (1990 to 1995). It is well below the ‘boom’ years which preceded the financial crisis.

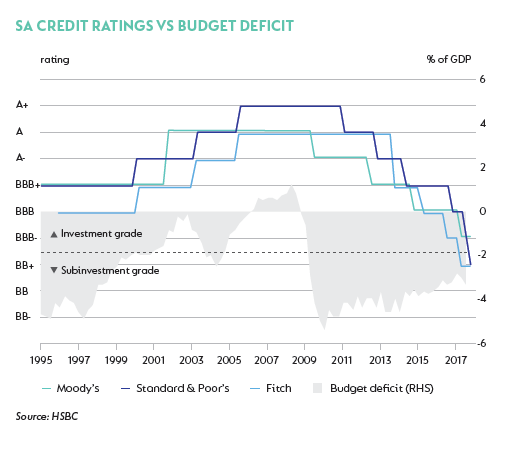

Critically, however, is that since 2015, on a per capita basis, real growth has been contracting – for the first time since the early 1990s. The fiscal position has deteriorated noticeably and the country’s sovereign ratings have been downgraded five times since 2012, leaving SA with a subinvestment grade – back where we were in 1994.

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

It is ‘easy’ to say we lost our way, that the country was captured and that the global financial crisis derailed growth because commodity prices collapsed, which had a knock-on impact on the fiscal position and the economy more broadly. All of these reasons have some truth in them, but if we look very hard at the numbers, and our own history, we have to acknowledge that even without these developments, the economy would have faltered. An urgent remedy is required.

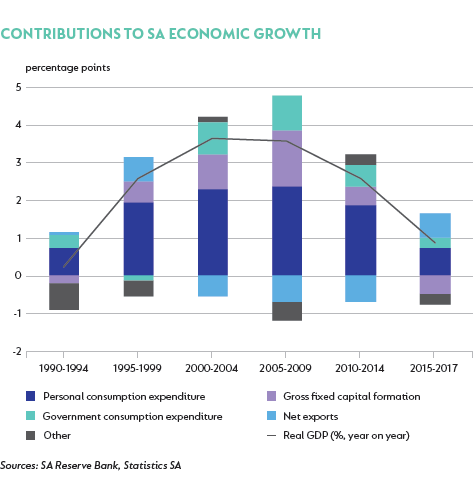

Much can be learned from looking at the composition of SA’s growth in five-year(ish) clips from the period just before the democratic transition to where we are today. In this way we can see what drove output, and make an assessment of the conditions which influenced growth.

On many occassions, SA was affected by natural disasters or impacted by global events, ranging from the political and economic sanctions of the 1980s to the emerging market and financial market crises that ensued in the late 1990s, and the financial crisis of 2008/2009. But throughout, domestic economic and policy decisions have had a meaningful impact on growth.

If we start with the period 1990 to 1994, average growth was just 0.2% and per capita growth fell at an average rate of -2.2%. This dismal performance came at a time when the apartheid regime was failing and the economy was suffering the lingering effects of the economic sanctions imposed on SA since 1986. The economy operated under a massive balance of payments constraint because there was no foreign funding available, which meant the country had to run current account surpluses.

In 1990/1991 the country suffered a debilitating drought. Household spending was nonetheless the biggest source of demand, aided by government consumption. Investment was negative and the country maintained a (necessary) small trade surplus.

The post-1994 election period saw the economy liberalised and reintegrated into the global economy. Importantly, the trade boards were abolished, and regulations were relaxed and many discarded. The regulatory environment was simplified and access to global financial markets saw the balance of payments constraint ease.

Exposed to international markets, the domestic economy became more competitive and investment picked up. Government adopted the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), with clear economic and social objectives, and began its implementation. Despite successive emerging market crises from late 1997 through 2000, average GDP was 2.6% and per capita growth turned positive, averaging 0.8% over this period.

The increase in investment and government spending through 2000 to 2004 saw the current account deficit widen, leaving net exports a detractor from growth and the country exposed to the vagaries of international capital. Government’s economic policy through this time was determined by the Growth, Employment and Redistribution Strategy (GEAR), which broadly aligned policy to RDP objectives and was generally in line with Western liberal economic philosophy, advocating relatively tight monetary and fiscal policy objectives.

The independent SA Reserve Bank (SARB) adopted an official inflation target in 2000 and GDP growth accelerated to 3.6%. Social grant policy was implemented in 2004 and per capita income gains accelerated again to 2.4%. Over this period, inflation moderated from over 8% in the previous five years to 5.5%, and by 2004 debt to GDP was just 34.4%. Despite the improvement in growth and domestic fiscal position, there was much internal dissent about the effectiveness of GEAR to deliver the objectives of the RDP. Amidst much opposition, including from politically powerful unions, GEAR was never fully implemented, and commitment waned.

Domestic economic policy floundered from about 2005 to 2009, but growth was buoyed by the enormous uplift in global economic momentum, domestic credit growth and financial deepening, and crucially, the commodity boom. Consumer spending surged, the domestic housing market took off and capital expenditure boomed as government and the private sector began to prepare for the 2010 Soccer World Cup.

In 2007, Jacob Zuma was elected as the ANC president and became national president in 2009. By this time, GEAR had been abandoned and the fledgling Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative never really saw daylight. Under president Zuma, the broad growth strategy fell under the National Development Plan, but economic vision became more diluted as the newly created department of economic development, the department of trade and industry, and the National Treasury all operated within different philosophical and capacity constraints. Despite this, SA’s commitment to conservative economic policies, and the strength and resilience of its political and economic institutions saw rating agencies hold SA at high investment grade ratings through this period.

The period following the financial crisis (2010 to 2014) saw all GDP components deliver smaller contributions to output. In part this reflected the weak global environment and commodity price collapse, which had a material impact on mining and manufacturing as well as on government revenues. Through this period, government embarked on a counter-cyclical fiscal policy – expenditure increased to 31% of GDP, driving a more developmental agenda which manifested in a massive swelling of government payroll. GDP growth averaged 2.6%, but after a relatively long period of sustained growth in per capita GDP, this now started to stall.

In addition, political events from around mid-2012 started dragging on economic growth, which averaged at just 0.9% since 2014. Per capita GDP was falling for the first time since the early 1990s. There were three main reasons: global growth tailwinds had faded, commodity prices had been depressed, and lastly, extractive political policies undermined both confidence and the ability of economic institutions to provide an environment in which private sector investment could thrive. Consumer and business confidence plummeted and with it, investment and consumption. Household spending – still the largest driver of growth but to a much smaller extent – was squeezed by depressed profitability, lower income growth, (at times) higher inflation and higher taxes.

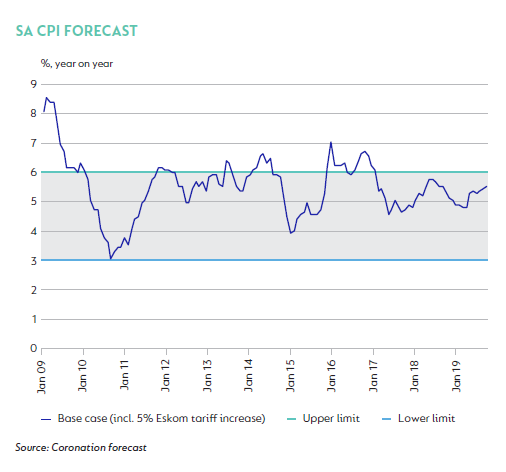

Growth in the year ahead will probably be a bit better than over the past three years, provided the global backdrop remains as supportive as it has been last year. It seems reasonable that political uncertainty may moderate, and a few interventions to restore confidence will go a long way to easing some of the constraint on both investment and consumption. At this stage, inflation looks set to remain comfortably within target, especially following the Eskom tariff ruling awarding the state electricity provider an increase of just 5.2% in 2018. We see some room for the SARB to lower rates early in the year.

MUCH HINGES ON DOMESTIC POLITICS

Newly elected ANC president Cyril Ramaphosa campaigned on a mandate of a New Deal for the country and the economy. In an op-ed in the Business Day on the eve of the ANC’s December elective conference, Mr Ramaphosa put forth a number of practical proposals to improve confidence, boost growth and address endemic corruption.

Whether he can deliver on these remains to be seen, but he is certainly in a very powerful position as both president of the ANC and deputy president of the country, despite uncertain internal political constraints. And he has great experience and success as a skilled negotiator, so it seems reasonable to hope that with some capable, principled people backing him, he will be able to address some of the institutional challenges which inhibit growth to facilitate meaningful, pragmatic discussion between business, labour and the government, and possibly appoint capable people to key institutional positions and allow them to do their jobs. In many cases, institutions of good quality are still there, awaiting new leadership.

The biggest challenge to political and economic stability is SA’s very high level of income and wealth inequality, and falling per capita GDP severely aggravates this situation. As we have seen in other countries, this outcome foments at the heart of populist politics, and SA now has significantly fewer resources with which to meet this challenge.

To manage a very long road to ensure future economic stability, SA needs an economic vision which recognises honestly its failures, accepts fairly that both the public and the private sector are accountable, and acknowledges the available resources which we have to work with. We have indeed been here before – the democratic transition came with hope, and a broken economy.

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal