Since narrowly winning the leadership of the ANC in December 2017, president Cyril Ramaphosa has made meaningful changes to his Cabinet and some state-owned entities. However, there are still legitimate concerns about his ability to make sufficient robust leadership changes to reverse the ruin that undermined policy and growth under his predecessor. But we are off to a good start.

WHAT HAS CHANGED? PRESIDENT RAMAPHOSA HAS BEEN VERY BUSY

At the end of January, even before he became president, Ramaphosa appointed a new board to embattled electricity utility Eskom in an effort to halt its decline and avoid a ratings downgrade. President Zuma stepped down on 14 February after tense negotiations and Parliament elected Ramaphosa the following day. On 16 February, newly elected president Ramaphosa delivered the delayed State of the Nation address, reiterating his election promise to foster growth, create jobs, reduce poverty, provide policy certainty, deal decisively with corruption and restore integrity to state institutions.

On 26 February, the president appointed his Cabinet, replacing almost a third of the existing ministers and almost all of those tainted by accusations of graft. Importantly, he appointed experienced ministers to key economic institutions, notably former minister Nene back to Finance and minister Gordhan to Public Enterprises. Minister Mantashe should be a capable set of hands at Mineral Resources.

Behind the scenes, investigations into corruption at Eskom continued, with heated Parliamentary hearings, and Justice Zondo appointed his team to undertake the enquiry into state capture. More recently, Ramaphosa suspended SARS commissioner Tom Moyane under whose watch revenue collection has faltered and tax morality fallen. He then appointed veteran Mark Kingon as interim commissioner. That is a lot of change in four months!

ECONOMIC CHANGE HAS BEEN LESS DRAMATIC, BUT VISIBLE NONETHELESS

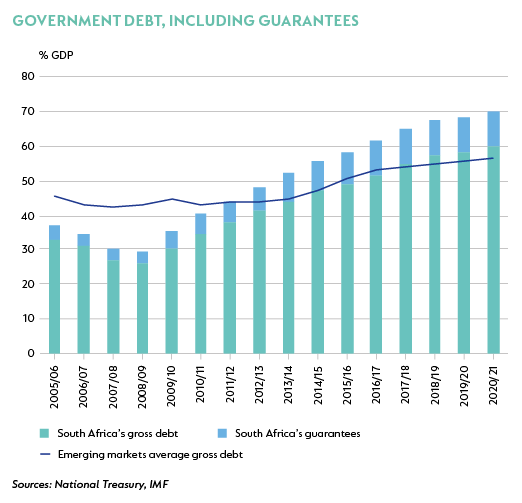

In February, former finance minister Gigaba presented the Budget, which was a considerable improvement on the Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) he tabled in October last year. The Budget detailed R36 billion in revenue adjustments, the biggest contribution coming from an increase in the VAT rate from 14% to 15%, effective 1 April. This intervention has always been viewed as politically challenging to deliver and the signalling attached to the change is almost as important as the revenue generated by it. A further expenditure consolidation of R85 billion over the next three years was also put into the Budget, of which R57 billion has been ‘reallocated’ to fund free higher education. Despite these changes, the forecasted main budget deficit for the coming year is -3.8% of GDP, from an estimated -4.6% in 2017/2018. This is better than the profile laid out in the MTBPS, but not back at the intended consolidation detailed in the previous Budget. This implies a slower pace of debt accumulation, with debt rising to 56% of GDP in 2020/21.

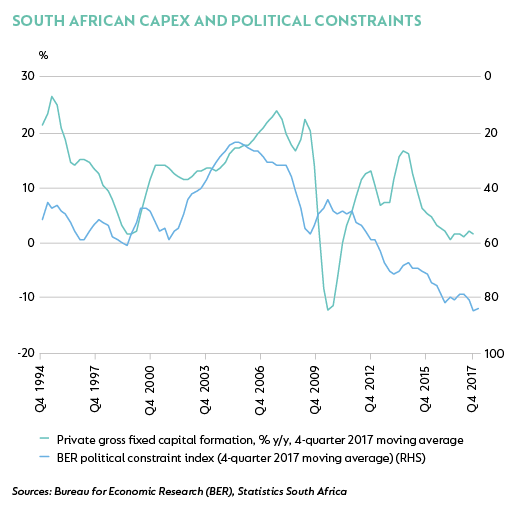

GDP growth surprised to the upside in 2017’s fourth quarter. As a result, growth for the year as a whole was moderately stronger than expected, given the chronic political uncertainty that intensified last year. GDP was 1.3% in real terms in 2017, from just 0.9% in 2016, with an acceleration in the fourth quarter of 2017 to 3.1% quarter on quarter, seasonally adjusted and annualised, and equivalent to about 1.9% year on year (y/y). The acceleration was reasonably broad based across sectors, and from a demand-side perspective, household spending rose smartly, up 2.7% y/y (3.6% quarter on quarter, seasonally adjusted and annualised). Capital investment recovered off a protracted weak base to grow 0.3% y/y (7.4% quarter on quarter annualised). With the rise in investment, imports accelerated too, offsetting some of the positive impact on growth. Elevated terms of trade remain an ongoing support for exports.

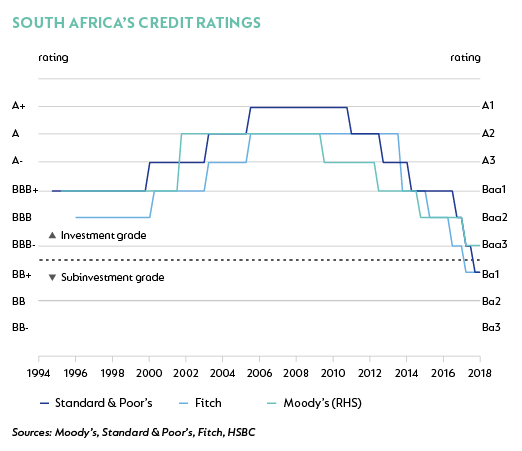

Together, these changes were enough to mitigate the final clear danger of a ratings downgrade, which would have led to South Africa’s exclusion from the Citigroup World Global Bond Index. On 23 March, Moody’s Investor Services not only decided to keep South Africa’s sovereign credit rating unchanged, but also decided to move the country from a negative outlook to stable. This implies that, for now, further ratings actions with serious potential negative consequences have been pushed back.

In February consumer inflation fell to just 4.0% y/y on a combination of falling food inflation, lower fuel prices and a moderation in underlying services inflation. Core inflation, which strips out food, fuel and other energy, was just 4.1% y/y – the lowest rate of price acceleration since 2011. The outlook for inflation at this stage is benign. We expect CPI to remain comfortably within the South African Reserve Bank’s 3% to 6% target band, with a forecast average of 4.8% in 2018 and 5.2% in 2019, anchored by low food inflation, the tailwind of currency appreciation and slowing service inflation.

WHAT REMAINS THE SAME? THE UNDERLYING POLITICS

South Africa has always faced the challenges of a much-divided political society. Race, culture, history, age, rural-urban divisions and different political and economic ideologies are all interwoven, and it will be hard to achieve both a unified vision and consensus.

Milton Friedman said, “Hell hath no fury like a bureaucrat scorned”. With an outcome as close as the ANC election in December, factionalism and resistance to change still exist within the ruling party. While the process to expose and eradicate corruption may well be under way, there is still representation of many opposing interest groups within the party leadership that may be challenging to navigate.

While Ramaphosa’s election has clearly brought change and there is optimism that the country is being steered onto a more sustainable path, it will take a long time to move on from what became the political norm of incompetence, corruption and lack of accountability. The ramifications of this will present their own challenges, not only to the economy but also to the social and political landscape. The ongoing deterioration in education standards, the failure to properly skill young people, the inadequate provisioning for investment in infrastructure and a history of misallocation of fiscal resources all need to be overcome.

Outside of the ruling party, the official opposition the Democratic Alliance has been embroiled in an internal dispute and severely affected by the protracted drought in the Western Cape. Navigating support into the next election is going to be challenging. The more radical Economic Freedom Fighters, who have lost their rallying call for land expropriation without compensation to the ANC, will also have to reinvent themselves.

We cannot overstate the economic risk posed by state-owned enterprises that have been maladministered for extended periods of time, entrenching corruption and incompetence to the point of failure. Interventions into management of Eskom and South African Airways will help, but the institutions themselves, the associated contracts and their ability to fulfil their economic obligations in a sustainable manner have not yet changed. It will require actively addressing entrenched corruption, vision, time and diligent efforts at rehabilitation to turn these entities around.

THE LONG-TERM ECONOMIC CHALLENGES

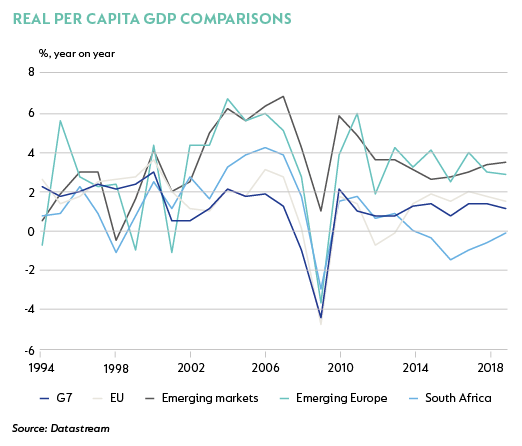

Coming off a stronger base and coupled with the political changes we have detailed, it is reasonable to expect growth to improve. We forecast GDP growth of 1.8% in 2018 and 2.2% in 2019, fuelled by an acceleration in consumption expenditure (as household confidence and real incomes recover), balance sheets that are in reasonably good shape and some growth in investment returns. While this acceleration is a welcome relief from three years of growth at about 1%, it is a far cry from the average 2.8% since 1994, and well below the average emerging market growth rate of 4.4% over the past three years. It is also not enough to reverse the downward trend in per capita GDP growth, which is crucial for improving dire levels of poverty and inequality. Available data paint a mixed picture of activity at the start of 2018, despite the more upbeat sentiment. The Purchasing Managers’ Index consolidated early gains in March, slipping back to 46.9 from 50.8 in February. Mining production has been a little better than expected, but manufacturing was weaker. Trade data have been weak, but early-year volatility may be distorting the hard data.

The long-term economic challenges are serious. South Africa needs a pragmatic and accelerated approach to transformation. The open debate about land expropriation needs to be clearly defined. It is already a drag on growth and sentiment, and carries material risk of becoming difficult to contain if not agreed urgently. This need for clarity in policy extends beyond land to mining, labour, the future and ownership structures of state-owned entities and a real need for a new approach to education. For the allocated budget to education, the end-delivery is woefully poor.

THINGS LOOK BETTER, BUT MATERIAL CHANGE REQUIRES VISION, COMMITMENT AND CONSENSUS

This may well be the start of better things for the economy and for South Africans. It is safe to say that most people feel it is certainly much better than it was. However, it will require vision and consensus commitment for the political changes to become socially and economically real, durable and entrenched. Practically, turning around the numerous broken state institutions, in addition to the state-owned enterprises, is going to be a Herculean task, and it is not clear that there are enough skilled people available to undertake it. Still, growth generates options and resources. If the new government can do enough to sustain an improved rate of growth, it will be easier to implement reforms to raise potential meaningfully.

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal