ECONOMICALLY, IT HAS been a very disappointing start to the year. After a long period of political and economic deterioration, the fast pace of political change after the ANC elective conference in December should have heralded the start of a recovery in confidence and growth. And in part, this did happen – president Ramaphosa moved swiftly to appoint a cabinet which mostly replaced poor ministers with good ones, the Budget delivered a decent political commitment to consolidation, Moody’s not only did not downgrade the sovereign rating to subinvestment grade, it moved the outlook to stable, and consumer and business confidence improved visibly. But growth did not.

WHAT HAS HAPPENED?

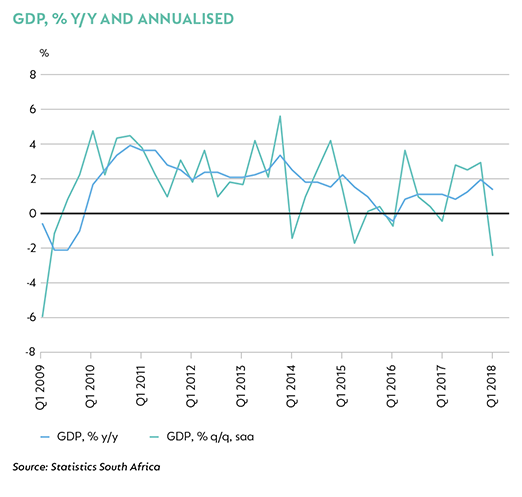

GDP growth contracted in the first quarter of 2018 by -2.2% quarter on quarter (q/q) seasonally adjusted and annualised (saa) and was just 0.8% year on year (y/y). While data from the fourth quarter of 2017 were particularly strong (surprisingly so, given the prevailing political uncertainty at the time), high-frequency data published in the first quarter of 2018 suggested that activity was a lot slower at the start of the year, and that the degree of deceleration was greater than expected. The biggest detractor was a 24.4% q/q saa contraction in agricultural production, which cut 0.7% off growth. Both mining and manufacturing output was significantly weaker following a surge in the fourth quarter of 2017, but weakness in other sectors, including utilities and construction, was more pronounced than expected. In particular, activity in the tertiary sector of the economy stagnated, with some resilience in finance and government the only real light spot overall.

Looked at from the expenditure side of the economy, fixed investment was surprisingly weak, falling -3.2% q/q saa, up just 0.2% y/y off a weak base. Again, the acceleration in the fourth quarter was stronger than expected. Another big disappointment came in with a fall in exports of -16.5% q/q saa and a total detraction from growth by net exports of -3.1 percentage points. Elsewhere, household spending slowed to 1.5% from 3.6% q/q saa. Accounting for 60% of real GDP, this is traditionally an important driver of growth momentum, and while the absolute rate of growth is a little weaker, it remains resilient – the slower moderation in the first quarter of 2018 is not surprising given the fourth-quarter surge.

The weakness in net exports points to a widening current account deficit and may temper growth expectations further. While global activity slowed in the first quarter and is also expected to rebound later in the year, this remains a vulnerability, not only for better growth but also for the currency.

Looking ahead, there is good reason to expect growth to improve from here, albeit at a slower pace than hoped. First, data from the first quarter of 2018 were affected by a number of one-offs which should recover, including the impact of a smelter outage on platinum group metal output (23.3% of mining production), an oil refinery closure which handicapped manufacturing output, and seasonal adjustment related both to Black Friday retail spending late last year and the timing of the Easter holiday this year.

While high-frequency data for the start of the second quarter of 2018 have continued to disappoint (retail sales, mining, manufacturing, business and building confidence), households in particular are in a relatively good position to increase spending, with solid real wage growth seen, improved consumer confidence and reasonably solid credit metrics emerging in data from the National Credit Regulator. Growth of above 2% in household spending remains a reasonable expectation at this time.

A meaningful productivity and job-generating increase in capital investment is likely to take longer. It is the nature of large industries in South Africa to require long lead times for investment, and despite the changing political backdrop, policy in key sectors remains uncertain. The renewed debate about land expropriation is unhelpful too, and it seems likely that companies will need more certainty (and durable global demand) to generate meaningful capital commitments. That said, even a small increase in inventory accumulation could provide some short-term growth momentum.

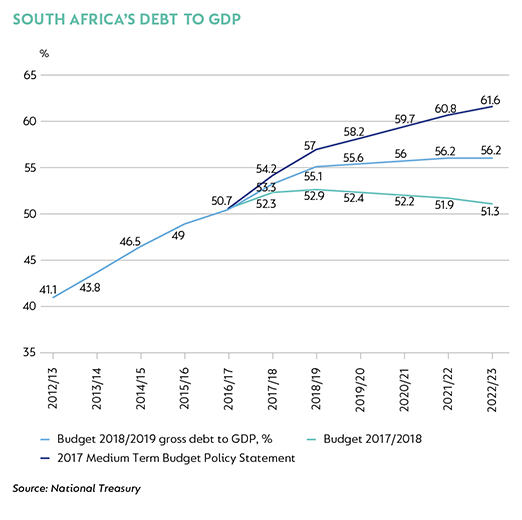

With growth disappointing, other concerns have become more heightened. South Africa’s vulnerable fiscal position was rendered only slightly (and possibly temporarily) less so with the Budget that was tabled in February, and the decision to support revenues with a 1% increase in value-added tax. Sustained consolidation of the deficit and moderation in the pace of debt accumulation, which accelerated meaningfully after the financial crisis in 2009, require both an improvement in the pace at which revenue is collected as the economy grows (tax buoyancy) and a tight rein on expenditure, notably the wage bill. Low growth threatens the former, although there are some signs of improvement here. On the latter, the public-sector wage agreement, which almost resulted in a strike, was a little more generous than budgeted, and will add to expenditure over the next three years. While this is not yet enough to fully undermine Budget projections of a deficit of -3.6% of GDP this year from -4.3% last year, the added burden of state-owned entities under significant pressure means that South Africa’s fiscal position is still very vulnerable.

HOW TO THINK ABOUT THE ECONOMY GOING FORWARD?

The weak economic outcomes are a reality check, a reminder that the deterioration in political and economic conditions has taken time, and so will the remedy. At the end of the day, the practical reality of a weak economy in which both consumers and businesses have suffered low or contracting growth in an increasingly unstable political environment has created a situation where intent and feeling better are not enough to motivate spending.

To give credit where it is clearly due, a lot has happened to halt the deterioration in both political and macroeconomic variables. Significant changes have been made at both ministerial and institutional level, and various regulatory and governance changes were initiated to start healing ailing parts of the system. Committed political and business leadership has worked tirelessly to not just talk about these interventions, but to deliver justice and generate committed capital. However, this process was never going to be easy or straightforward, and we are reminded daily that not everyone wants the same thing – vested interests, poor practice (both public and private) and deeply ingrained but differing perspectives are all challenges which will need to be navigated to see an economic recovery.

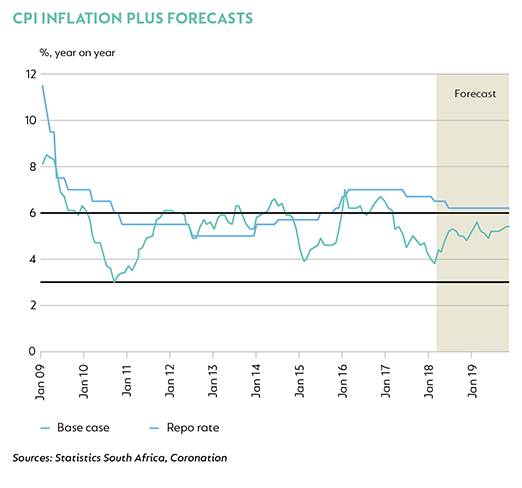

For the remainder of this year and the next, with many uncertainties not limited to internal political dynamics, the 2019 election and global cyclical momentum, domestic fundamentals still support better growth than we have seen to date. Aside from the one-offs which we expect to reverse by the end of the first half of 2018, we anticipate a pickup in household spending, an area of resilience in the first quarter, and some improvement in net trade. We think capital investment will be less weak, but will take longer to recover, with growth forecast at 1.6% this year (1.8% previously) and a solid 2.2% in 2019.

Disclaimer:

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal