Investment views

Addendum 4: Stress testing worst-case scenarios

- assessing asset class performance in weak state regimes

GHANA

While long a darling of the Sub-Saharan region for all the right reasons: resource-rich, a functional democracy, a high growth economy with favourable demographics, and a relatively open and market-orientated economy, Ghana also has a sustained history of poor fiscal management and an abysmal track record of failed reforms and rebalancing mechanisms. This eventually culminated in fiscal unsustainability and a request to the IMF to assist in 2022, after struggling to offset the damage wrought by the onset of Covid two years earlier.

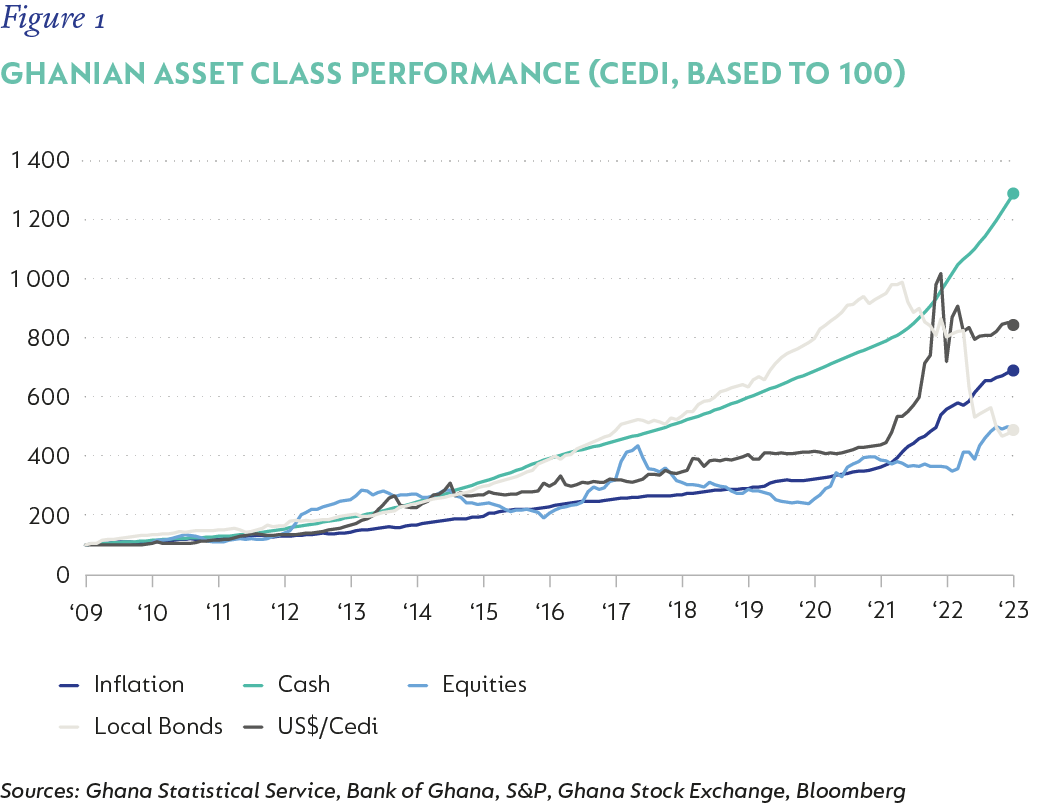

As illustrated in Figure 1, Ghana’s long-term asset class performance is curious and deserves some explanation.

As is evident, the performance of cash (three-month government Treasury bills) over the long term on absolute, relative, nominal, and real bases – and even in hard-currency (Ghanian Cedi) terms – is noteworthy. Yet, it is this very remarkable feature that goes hand-in-hand with Ghana’s challenging fiscal backdrop of the past several years, i.e., the cost of borrowing for the sovereign was high and poorly managed. In the case of longer-term debt, investors paid the price for this in the bond restructuring negotiated as part of Ghana’s IMF programme. But, as is mostly the case, Treasury bills were excluded from the restructuring envelope – hence the cumulative compounding effect of sustaining cash rates, at their minimum in the mid-teens – was allowed to continue. So, this explains the high level of cash returns over the long term in Ghana. It also sheds light on why bonds failed to sustain their yield and return advantage when the prospect and then realisation of a haircut became increasingly a risk. However, what about the relatively lackadaisical outcome seen in Ghana’s equities?

The explanation is simple and has an important lesson to impart when considering any prospective sphere of long-term asset class returns within an environment dominated by a struggling sovereign and macroeconomic instability. Ghana’s equity market is exceptionally shallow, undeveloped, and unrepresentative. Indeed, even now, the top three listings make up c. 88% of the entire stock exchange by market capitalisation. Of these, AngloGold Ashanti makes up 62% and Tullow Oil c. 13%. This means that two, single-commodity, high-risk resource extraction entities make up 75% of the entire market in Ghana! This is less of an asset class and more of an investment trap…

Thus, the fairest approach is to recognise that Ghana’s equity return experience isn’t really representative of anything at a higher level or macro scale. There are no generalisations to be made here. However, there is a lesson: asset class composition is important. In Ghana’s instance, there was a very narrow thread between exposure to the equity market and the travails of the domestic macro and policy landscape. But, unfortunately, there was also limited diversification. Thus, while an equity asset class exposure in Ghana was relatively far removed (although not totally) from the difficulties that the Ghanaian government made for itself – it wasn’t removed to something appropriate for a diversified investment portfolio.

Disclaimer

SA retail readers

SA institutional readers

Global (ex-US) readers

US readers

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal