Investment views

Bond outlook

The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity – William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming

The Quick Take

- Domestic assets are faltering under the twin burden of global trade tensions and domestic political brinkmanship

- Fundamental headwinds are the usual suspects – interest rates, government debt, low growth and policy inaction

- Growth is urgently needed – especially in an increasingly polarised world – but SA still seems to lack the political will to get it

The first quarter of 2025 was marked by significant shifts in global financial markets that have reverberated through South Africa (SA)’s economic landscape. Central banks, including the US Federal Reserve, signalled a cautious pivot, balancing growth concerns with persistent cost-of-living challenges. Global risk sentiment has soured as investors recalibrate their views and appetites amid new tariff policies and a strengthening dollar. The uncertainty on the magnitude of the impact of the Trump administration’s tariffs, counter-tariffs by affected countries, the deteriorating diplomatic relationship between the US and SA, and recent tremors within the Government of National Unity (GNU) around the Budget have weakened the appeal of SA assets.

Despite US bond yields compressing 30 basis points (bps) over the quarter, the SA 10-year bond weakened by c. 30bps due to SA-idiosyncratic issues (SA-US tensions and uncertainty with regards to Budget outcomes), driven by the steepening of the yield curve (maturities of 10-years plus moving more than shorter maturity yields). The FTSE/JSE All Bond Index (ALBI) and the FTSE/JSE Inflation Linked Bond Index (CILI) were both up 0.7% by the end of the quarter, behind cash at 1.83%, but still well ahead over the last 12 months (ALBI 20.16%; CILI 8.93%; Cash 8.03%). Emerging markets remained on the backfoot through most of the last 12 months, however in the last quarter, the dollar weakened slightly. The rand was among the beneficiaries, strengthening 2.8% during the quarter, leaving it c. 50 cents stronger than the same point last year (18.84 versus 18.33). This helped the local bonds outperform global bonds in dollars (3.62% versus 2.57%) and keeps their performance well ahead of their global counterparts over the last 12 months (23.49% versus 2.09%).

POLICY BLUES

The two fundamental issues that are persistent headwinds to local bonds are restrictive monetary policy and precarious government finances.

Local inflation has continually surprised the market and the South African Reserve Bank (SARB)’s expectations to the downside. This has been due to a combination of lower commodity prices (oil and food) and a very benign local demand environment. Inflation averaged 4.4% in 2024 and is expected to average 3.5% in 2025 and 4.6% in 2026. This is a significant moderation from the highs of 2022 and 2023 when it averaged 6.4%, pushing the repo rate to 8.25%. This moderation in inflation has also come in the wake of a marked slowdown in SA’s growth profile, with growth in the last two years averaging sub 1%. Growth is expected to pick up, but only slightly, given recent global developments, and is likely to come in at approximately 1% in 2025 and approach 2% in subsequent years – contingent on the durability of the GNU. Although this is significantly better than what SA has experienced in the last decade, it is still a far cry from the level of growth required to create sustained employment and consumption demand within the economy.

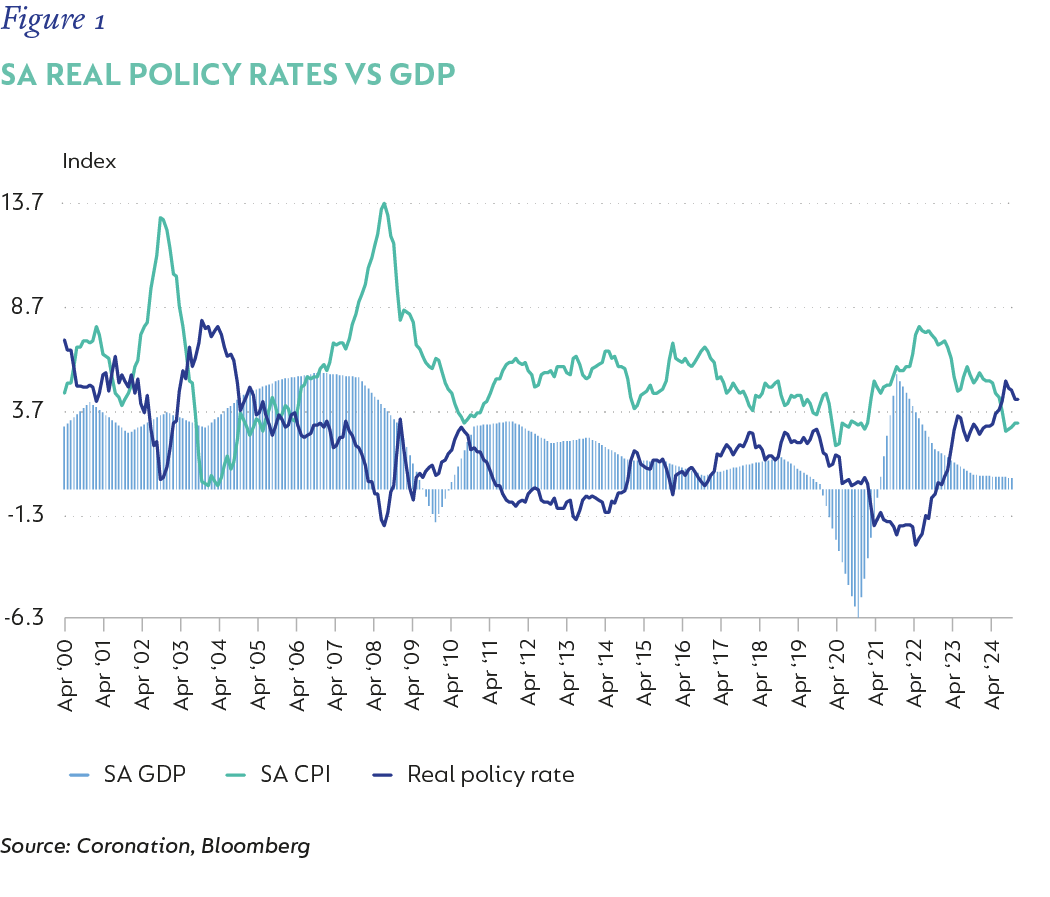

The recent Trump administration tariffs combined with the loss of business confidence in SA due to the GNU instability, risks placing growth on a lower path. Real policy rates in SA (Figure 1) are now at the most restrictive levels that they have been at since the early 2000s when inflation was in double digits, growth was c. 4%, and SA was only starting its inflation-targeting journey. Inflation is now very much under control at 4.5% but growth prospects remain in the doldrums. Why is it, then, that the SARB maintains real policy rates north of 4% when the historical norm has been 1.5%-2%? It is implicitly targeting inflation at a lower point (3%-3.5%). We maintain that a lower inflation target over the longer term is beneficial, however the high cost of funding in the local economy at a point when growth is faltering, is throttling the recovery, and rates should be 100bps to 150bps lower given current conditions. Unfortunately, the SARB is probably going to remain on this path, at best keeping rates stable going forward, unless global growth forces its hand. This might happen as the effects of the tariff hikes make their way through the global economy.

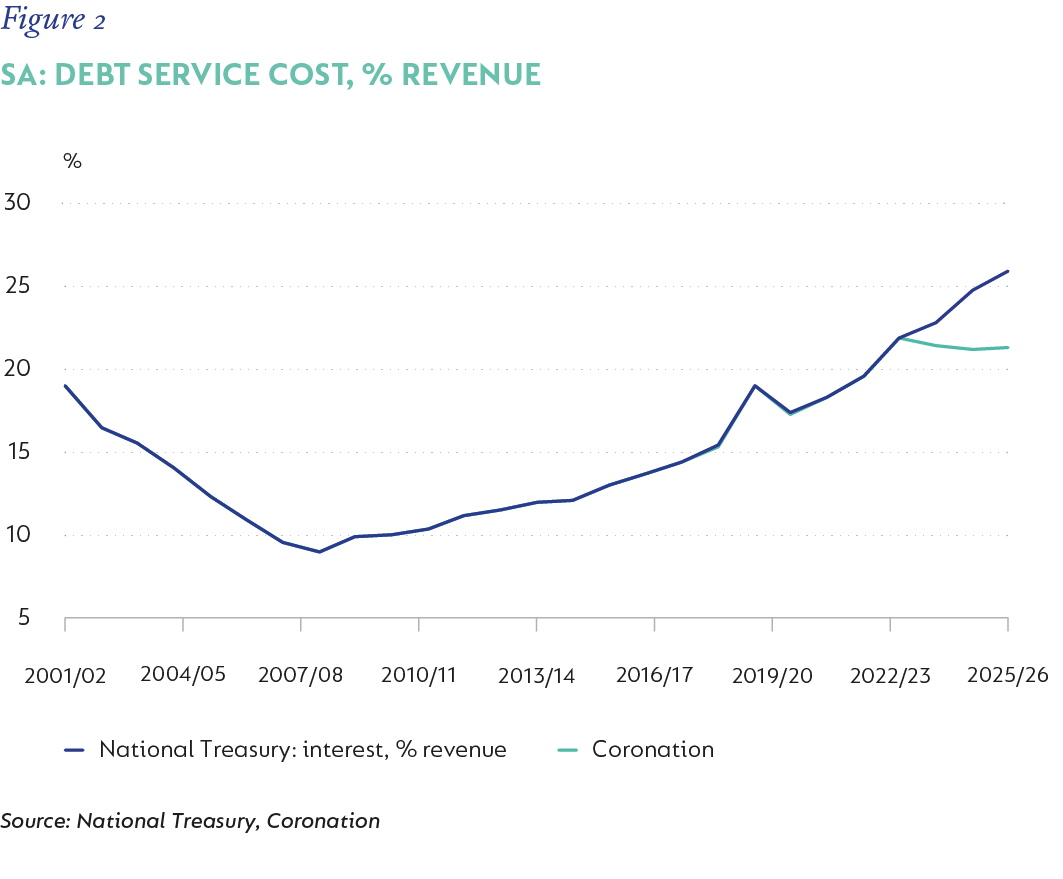

The recent Budget turmoil highlights the very difficult task that the country faces given its excessive debt load. On face value, the Budget sticks to its fiscal consolidation path by financing all new expenditure (increased front-line workers, Social Relief of Distress Grant and funding costs) through increased revenue measures (VAT hike, bracket creep and use of unallocated reserves). However, the increased expenditure is recurring and fixed, implying any fall off in growth and thus revenue, will create a larger funding shortfall, thus further reducing fiscal buffers and increasing the risks of a higher debt load going forward. In addition, National Treasury accounts for its debt servicing costs on a cash basis versus traditional accounting methods of accrual. This implies that it sets up its debt accumulation forecasts for disappointment, that is, it accumulates more debt than it forecasts. The risks are therefore heavily skewed towards a worse outcome on the Budget going forward if economic growth does not recover significantly. SA will continue to pay 20%-22% of every rand it collects as revenue towards its debt cost (Figure 2), with this number touching close to 30% in the next three years if funding costs don’t come down or revenue doesn’t bounce back significantly - i.e., SA sees higher growth.

WE MUST KEEP GOING FORWARD

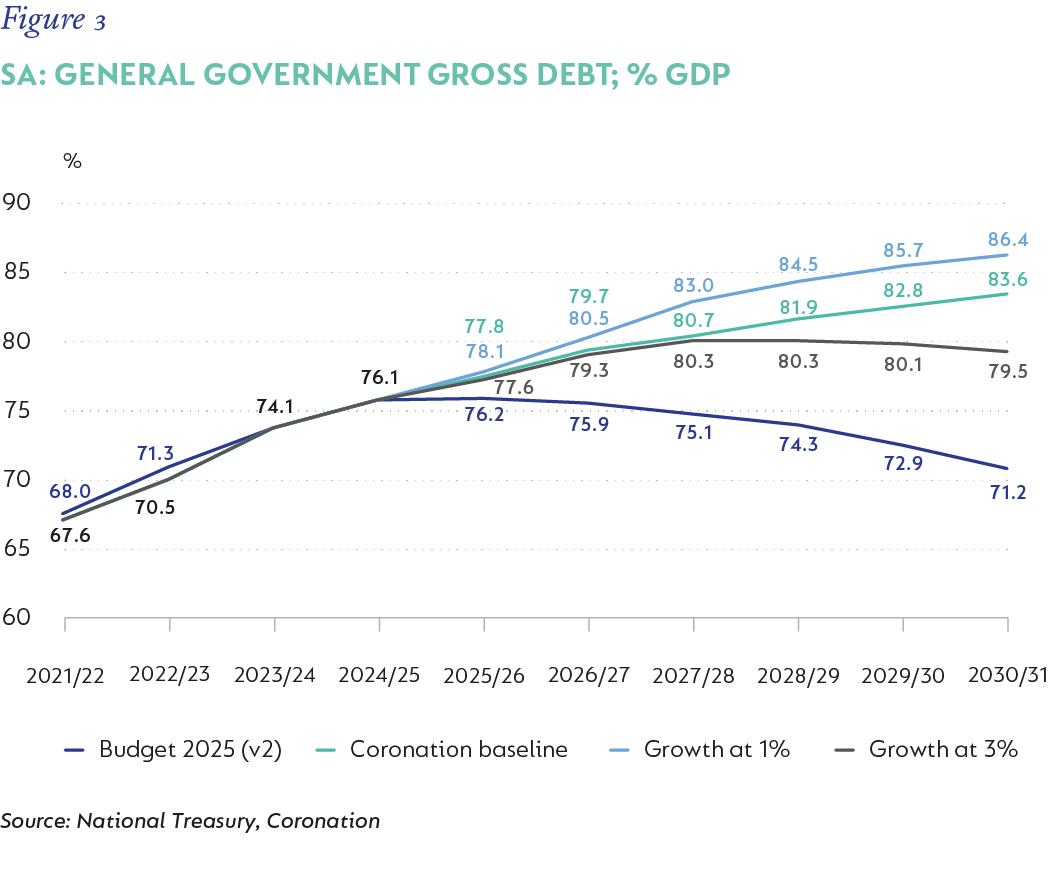

Anaemic growth is at the heart of SA’s fiscal mess. The formation of the GNU, which included the pro-business DA, helped bolster investor sentiment and removed downside tail risk from SA’s policy choices. While we have not yet seen significant policy shifts, the presence of the DA in the coalition government was enough to halt deterioration, reduce slippage, and prioritise needed reforms, fostering an environment in which growth could accelerate towards 2%. This is still substantially lower than what is needed but higher than that of the last decade. At the time of writing, it seems very likely that this arrangement will not continue in its current form, that is, the DA will either leave the GNU or be removed from its current positions within government. This will be a significant step back in SA’s recovery story and places the fiscal rehabilitation in great peril. Much of the reform process was started before the formation of the GNU and will definitely continue, but the risk is that the urgency behind implementation fades, lowering the growth trajectory. In addition, the recent Trump tariff actions will lower global growth, maybe not into recession, but enough to hurt a small export-driven economy on the southern tip of Africa. SA’s current debt load, as shown in Figure 3, requires a minimum of 3% real growth in order to stabilise.

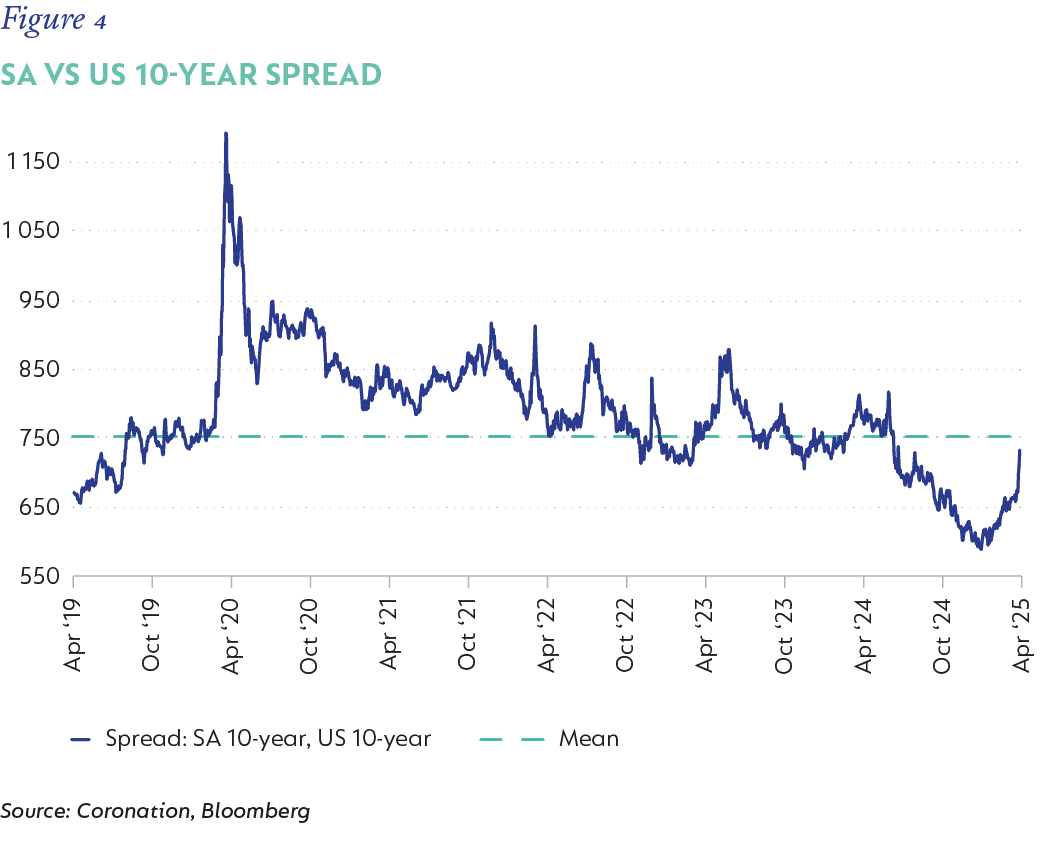

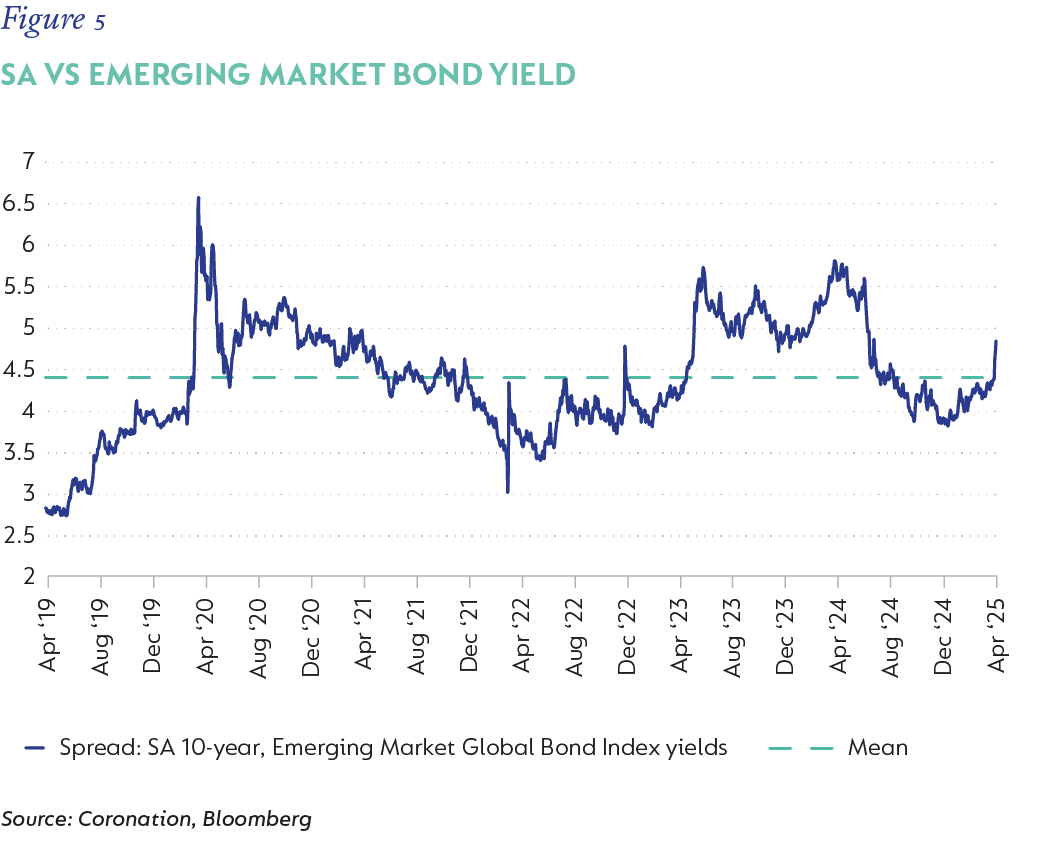

This leaves the outlook for South African government bonds (SAGBs) quite uncertain. Fundamentally, inflation should not pose a headwind for SAGBs given our relatively benign outlook. Lower growth could, however, provide some impetus for the SARB to reduce the repo rate, thus supporting the front end of the curve. Unfortunately, if growth does falter and reform implementation does not provide a fillip, the fiscal position will continue to deteriorate, weighing on the longer end of the yield curve as the bond supply would have to fill the void. The valuations of SAGBs are not cheap and, if we are to revert to levels last seen pre-GNU formation, bond yields could widen by a further 50bps-75bps. In Figures 4 and 5, we show the SA 10-year bond yield versus the US 10-year treasury note and the emerging market representative yield. One can see that yields would need to widen in both cases to return to pre-GNU type levels.

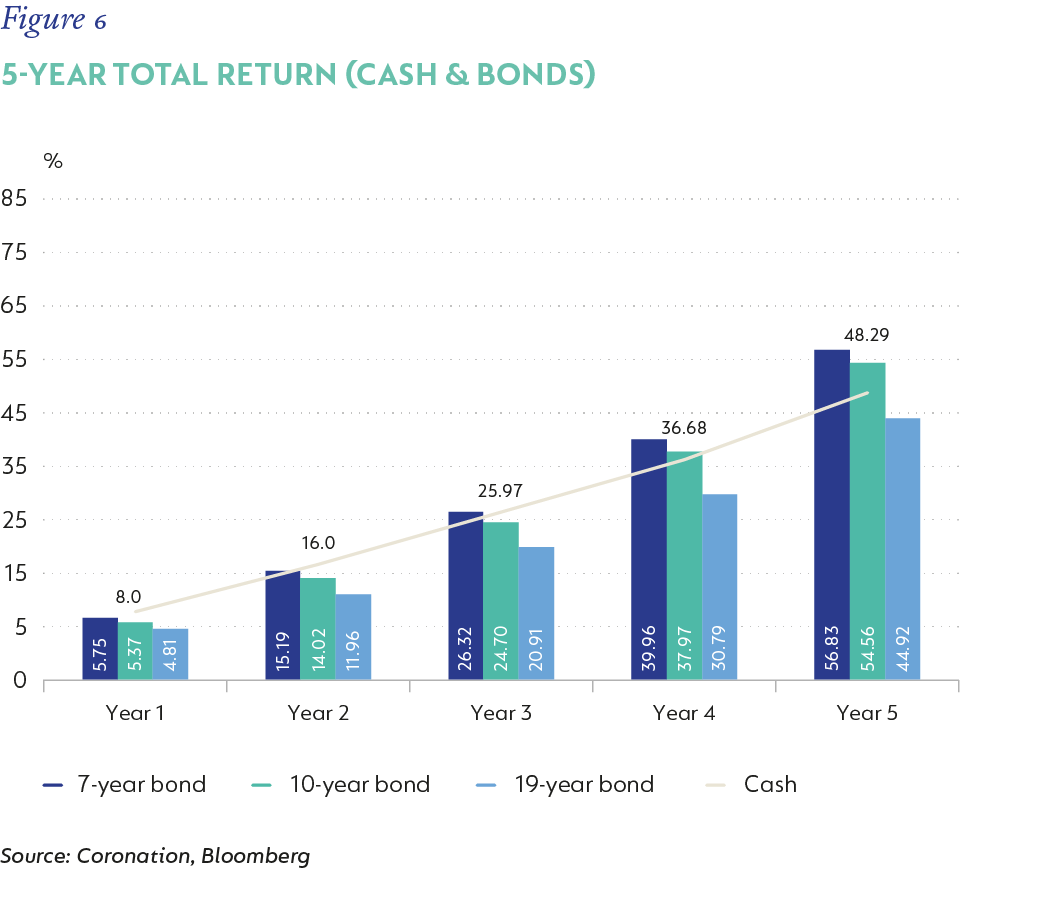

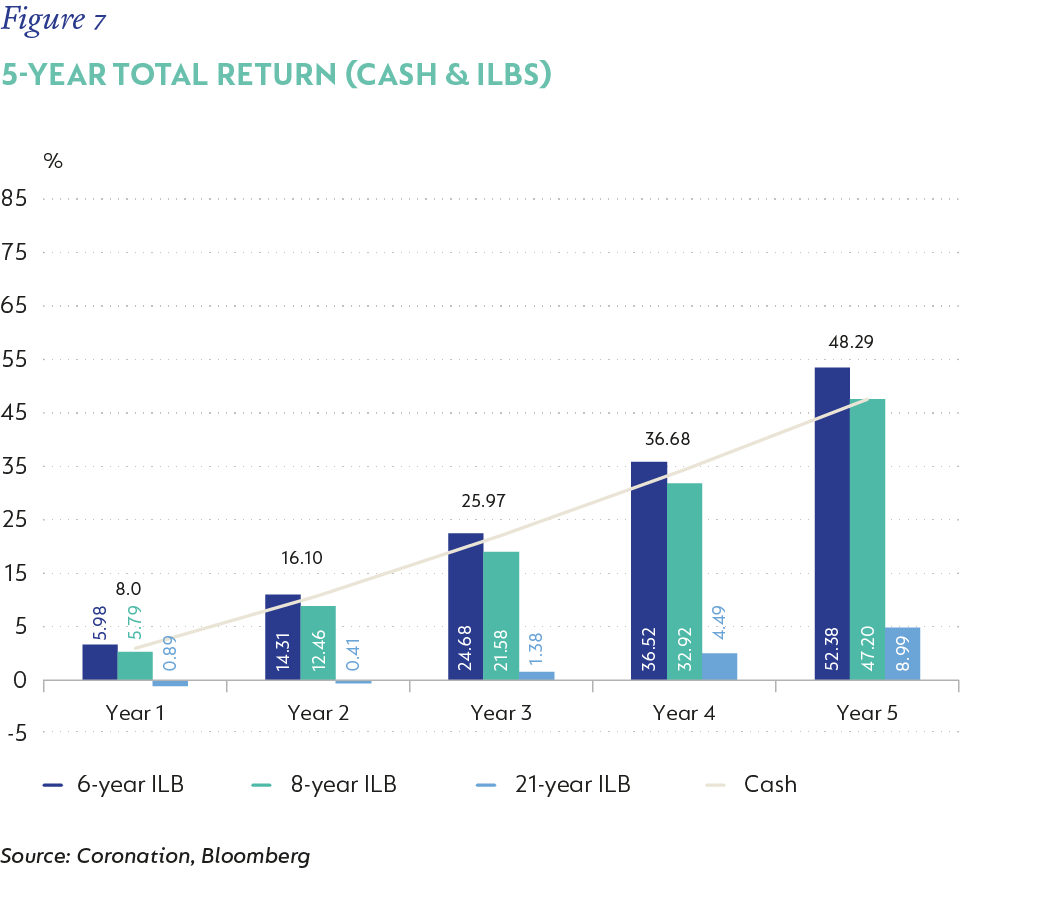

This is an extremely negative scenario and remains highly probable given the uncertain local and global landscape. A move wider in bond yields by 50bps-75bps would then place them at quite attractive yields (five years at 10%, 10 years at 11.7%, and 20 years at 13%). In the analysis below (Figures 6 and 7), we run a total return projection for nominal and inflation-linked bonds (ILBs) from current levels in a risk-off scenario (yields widen by 75bps-100bps per annum, cash rates reaching 8.5%, and inflation averaging 4.5%). It is quite instructive, that even current yields offer investors quite significant protection relative to cash over a five-year period, with the best protection being offered by nominal bonds with a maturity of less than 10 years and ILBs with a maturity of less than eight years. Thus, although current yields might not encompass a large enough risk premium given the highly unsettled current landscape, bond yields still offer protection over the long term relative to cash, and the widening should be an opportunity to reengage into their value proposition.

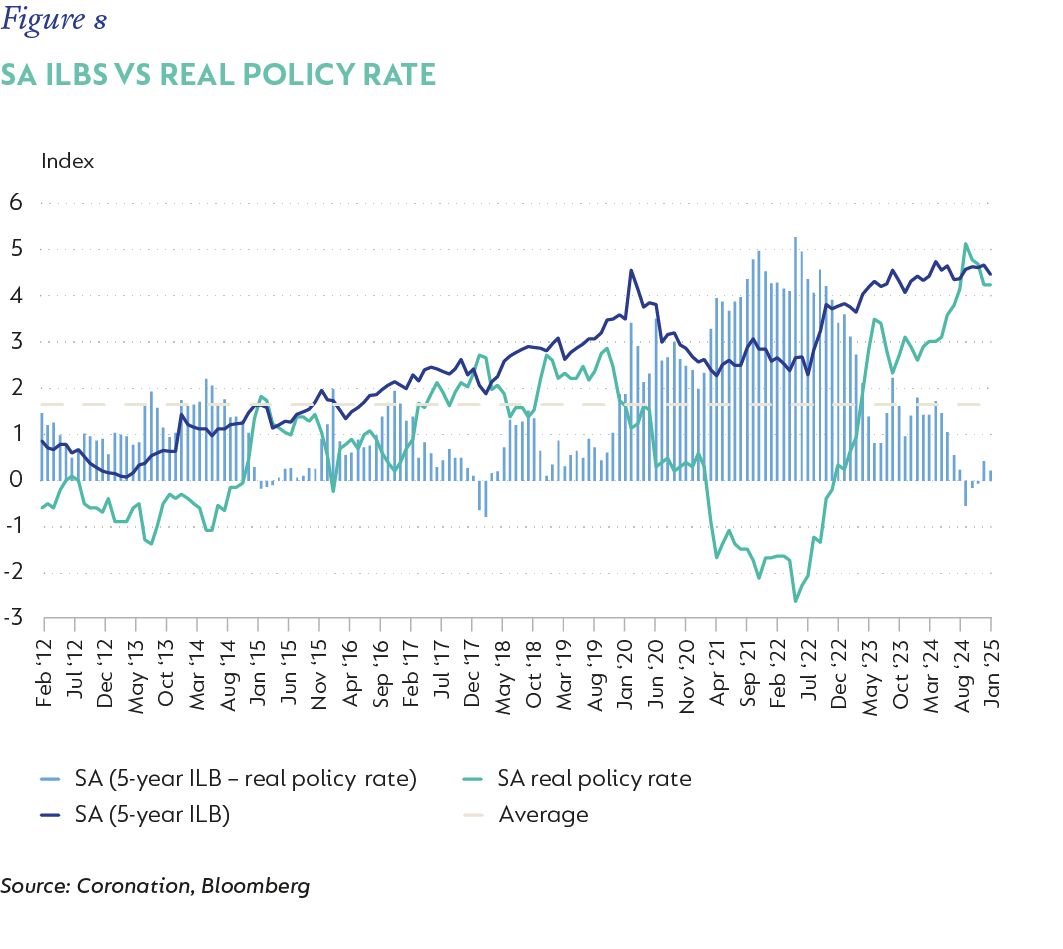

ILBs still offer eyewatering real yields of 4%-5% across the curve. These guarantee the holder a return of 4%-5%, in excess of inflation to maturity. However, over the last year, their performance has significantly lagged that of nominal bonds. Since their return is tied to inflation outcomes and inflation has been moderating quite aggressively, their yields have continued to creep higher to compensate for the higher yields on offer in nominal bonds. Furthermore, since the SARB has not been easing rates (and by implication the real policy rate) as much as it has in the past given the current levels of inflation, the real policy rate has acted as a floor for ILB yields (Figure 8). We continue to believe that the real policy rate remains too high given SA’s current growth and inflation outlook, and should moderate in times to come, thus supporting ILBs, allowing their yields to compress. Since these instruments carry a higher modified duration (capital at risk due to yield movements) than nominal bonds, they will outperform in such a scenario.

ILBs are also less correlated to nominal bonds given their inherent risk-protection attributes. These are present since inflation in SA has historically been very closely tied to the currency performance and because the currency is the release valve for any SA- (and global risk-off) specific difficulties, it has a direct feed through to inflation. This makes ILBs a good risk-offset to hold in a portfolio, specifically during risk-off events.

The changes in the global landscape have become less favourable for risk and emerging market assets. The effects of a global trade war will leave global growth floundering and export-driven economies will struggle in such an environment. The slowdown in global growth, once the immediate inflationary shock retreats, should compel global monetary policy to turn supportive, thus supporting global developed market fixed income. SA’s recent political turbulence makes it ill-placed in an unfriendly world. Local inflation should remain relatively well behaved, but a growth slowdown will have negative consequences for the country’s finances, suggesting a further risk premium needing to be priced into local bond yields. This would be further solidified if the GNU is reconfigured in a less growth and business-supportive manner. SA bonds are at risk of a wider repricing in yields and bond portfolios should remain neutral but ready to take advantage of weakness when it prevails. In addition, ILBs should be present in portfolios to provide some risk offset should the worse outcome materialise.

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal