Personal finance

The basics (and risks) of an investment in cash, money markets and bonds

Content in collaboration with Smart About Money

The Quick Take

- Cash and bonds can be used for diversification, capital protection and preservation, and may also add liquidity to a portfolio

- While bonds are generally considered to be lower risk than equities, some bonds are riskier than others

- Investors in bonds earn returns primarily via interest income, but capital gains or losses are also possible

Fixed income investments are generally lower risk and often used to diversify a portfolio, preserve wealth and generate a steady source of income. However, as we explain below, the fixed income universe is complex, and these investments are not without their own set of risks.

INVESTING IN CASH

The cash asset class comprises bank deposits and securities (often called cash equivalents) that can easily be converted into money in the bank.

Cash equivalents are issued by large, stable entities such as governments or banks and typically do not have a term (they are on call), or they mature in less than a year. Many of these instruments may be traded in the money market (as discussed below). As this is a wholesale market, individual investors will likely invest in cash through a bank deposit or money market fund.

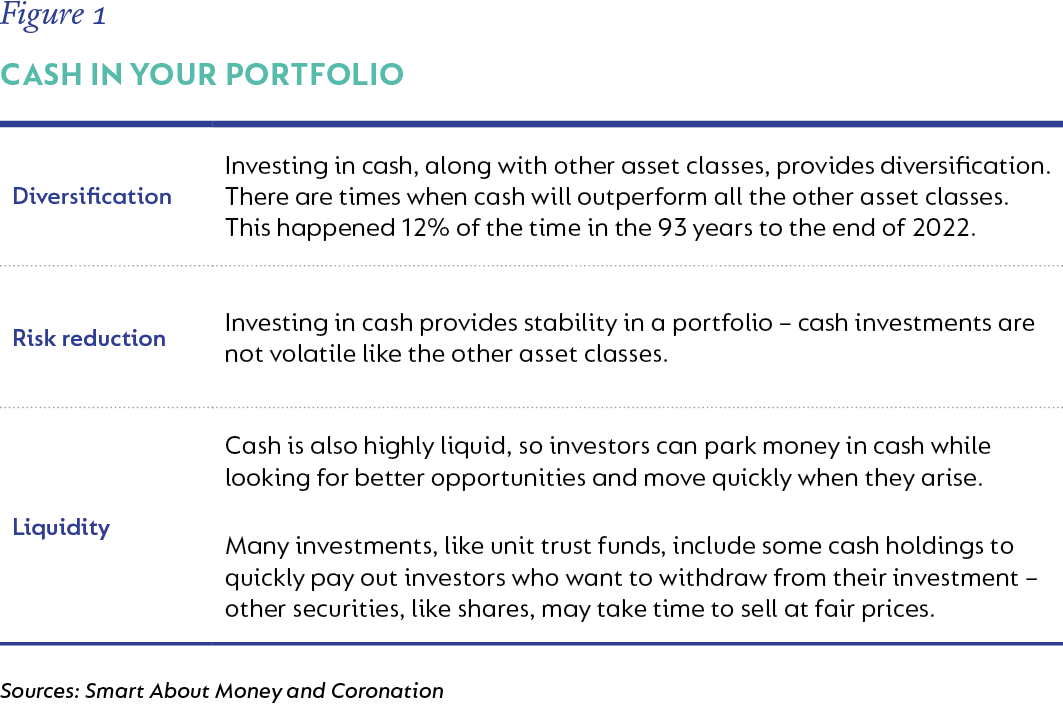

Investors invest in cash to earn interest, and the longer the term to maturity, the higher the interest the security will pay. One would also consider an investment in cash for the following qualities:

When investing in cash, investors need to be mindful that over more extended periods of time, cash will, on average, only outperform inflation by a small margin. It is therefore not a good idea to hold a large proportion of a long-term investment such as your retirement savings in cash as it will prevent you from achieving the growth you need.

You can read more about cash as an asset class here.

THE MONEY MARKET

The money market is where cash-like instruments with a term to maturity of less than a year are traded. These instruments are issued by banks, other companies, governments, and state-owned entities looking to borrow over the short term.

Money market instruments include:

- Treasury bills;

- Commercial paper from corporates and financial institutions;

- Interbank loans;

- Negotiable certificates of deposit;

- Banker’s acceptances;

- Promissory notes; and

- Call deposits.

As an unlisted market, these short-term instruments (call it loans or debts) are sold through events like bank auctions and traded through a network of interested parties.

The money market is used by investors who can invest or trade the large amounts involved (typically more than R1 million). It is therefore known as a wholesale market.

Interest rates on these bulked transactions are slightly higher than what you can get as an individual, and the instruments are generally relatively low risk because they are issued by credible institutions committing to repay investors’ capital in the near term.

The money market is similar to the bond market, but the term to maturity of the loans and other instruments issued is much shorter.

CAN I INVEST IN THE MONEY MARKET?

Individual investors can access the attractive interest rates available in the wholesale market through a money market fund that pools money from many investors to arrive at the necessary sums needed to invest (via a fund manager) in the money market.

A money market fund is a collective investment scheme which, like all collective investment scheme funds, is regulated by the Collective Investment Schemes Control Act. To protect investors, there are strict limits on what money market funds can invest in. In exchange, these are the only unit trust funds that are allowed to be offered at a fixed unit price.

These limits include a maximum loan term or maturity date of less than 13 months at an instrument level, a maximum average term to maturity for all the instruments held in a money market fund of 90 days and a maximum weighted average duration of all the holdings of 120 days. This reduces the risk of money market funds compared to other fixed interest funds that may hold instruments with longer durations and have longer average terms to maturity of all the instruments held (see our adjacent article on income funds).

HOW DO MONEY MARKET FUNDS MAKE MONEY FOR THEIR INVESTORS?

The return on a money market fund is known as its yield.

Money market funds earn interest from the instruments in which they are invested, which is distributed periodically to investors. The interest paid is quoted as the yield on the fund (the percentage return on the amount invested), and unlike interest on a fixed bank deposit, the amount paid changes daily.

You can choose to receive these distributions or reinvest them to increase the amount you have invested and thus the amount on which you can continue to earn interest.

The yields on money market funds differ between funds, depending on the instruments in which they are invested. The yields on the funds will change in response to interest rate changes announced by the South African Reserve Bank. Published money market yields are typically quoted as an average of the past week, but it is worth checking the fine print.

Money market yields are generally higher than what you would receive on a call account at a bank. The interest rates are more in line with what you would earn from a bank fixed deposit, but in a money market fund, you have access to your funds as you would with a call account deposit.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS FOR INVESTORS IN MONEY MARKET FUNDS?

While your capital is reasonably secure (you can generally expect to receive the same rand amount back when you want to withdraw), losing money on a money market fund is possible. This would happen when an institution such as a bank fails and cannot honour, or honour in full, the instruments issued to investors. However, the limits on the investments held by money market funds ensure that these funds are diversified across several institutions, which offer protection by minimising the losses you can incur.

Read more about money markets and money market funds here.

INVESTING IN BONDS

Bonds are fixed interest instruments that allow an issuer (typically governments, state-owned entities, parastatals, municipalities, and corporates) to borrow money for a certain period (term) on which it pays the lender a fixed interest rate for the term. When the bond reaches the end of its term, the bond issuer will repay its lender the original money that was borrowed.

Fixed-rate bonds are the most common type of bonds, but bonds may also offer interest that varies with policy interest rates or inflation. It is also possible to buy bonds that offer a discount on the face value of the bond and repay the total amount at maturity (zero coupon bonds) or convert to shares when certain conditions are met (convertible bonds).

Some bonds have very long terms, such as 10, 20 or even 30 years.

Government bonds issued in countries backed by strong economies are typically seen as relatively safe investments. If you hold them to maturity, you enjoy a guaranteed return and have little risk of not being repaid your money.

Credit rating agencies rate bonds based on the issuer’s creditworthiness. Investment grade bonds are generally of high credit quality, while sub-investment or junk bonds are much more speculative. The creditworthiness of an issuer can change over the life of a bond, hence affecting the credit rating of the bond.

HOW DO BOND INVESTORS MAKE MONEY?

Individual investors have the following options to invest in bonds:

- The interest paid on the bond (typically twice a year);

- A capital gain if the bond price in the secondary market rises, and you can sell it for more than what you paid.

The interest rate at which a bond is issued depends on the issuer, for how long the bond is issued and the current interest rates at which money is being borrowed and lent.

If the issuer is strong, and there is little risk of defaulting on the interest payments or repaying the bond when it matures, the interest rate would be lower. Less creditworthy issuers must pay higher interest rates to attract investors.

Governments are generally unlikely to default on bonds issued in the home currency as they can raise taxes or print money to repay bonds. Other entities may not have the same backup, so the bonds they issue must typically offer a higher interest rate to compensate for the higher risk.

HOW CAN INDIVIDUALS INVEST IN BONDS?

Individual investors have the following options to invest in bonds:

- Invest in a bond unit trust fund or exchange-traded fund that has exposure to several different bonds;

- Invest in a multi-asset fund with some exposure to bonds (read more about this option here); or

- Invest in RSA retail bonds (investments offered by the government that operate similar to fixed deposits).

You are likely to have exposure to bonds in your retirement fund as it is obliged to invest across various asset classes to comply with Regulation 28 under the Pension Funds Act, which is aimed at ensuring your retirement savings are properly diversified.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS INVOLVED WITH AN INVESTMENT IN BONDS?

1) Default risk

Bond issuers do, at times, default on the interest payments or repayment of the bond. This will cause the price of the bond to fall rapidly.

But when companies get into difficulty, bondholders are likelier to get their money back than shareholders.

Most listed bonds are structured so that bondholders’ claims are paid out first if the issuer goes bankrupt. In some cases, bondholders may have to accept a little less than the full repayment or full interest, but they are unlikely to lose all their money in the way that shareholders can.

2) Interest rate risk

Interest rate risk is the risk that arises for bond owners from fluctuating interest rates. For example, when a bond’s fixed rate is lower (i.e., less attractive) than the prevailing market interest rate, the bond's market price decreases (i.e., the value of your asset declines).

The longer the period to maturity for the bond in issue, the more significant the decline in its value in the secondary market. In turn, the market price of a bond will increase when its fixed rate is higher (i.e., more attractive) than prevailing market interest rates.

Interest rate risk is measured through the modified duration of the bond (or bond fund). It is good practice for fund managers to disclose the portfolio duration on its fund factsheet.

3) Inflation risk

When inflation is rising rapidly, the value of your bond and interest payments may not keep up.

Inflation causes interest rates to rise, leading to a decrease in the value of existing bonds. During times of high inflation, bonds yielding fixed interest rates tend to be less attractive.

Read more about bonds here.

Disclaimer

SA retail readers

South Africa - Personal

South Africa - Personal